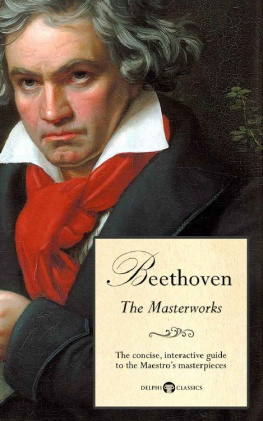

LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN

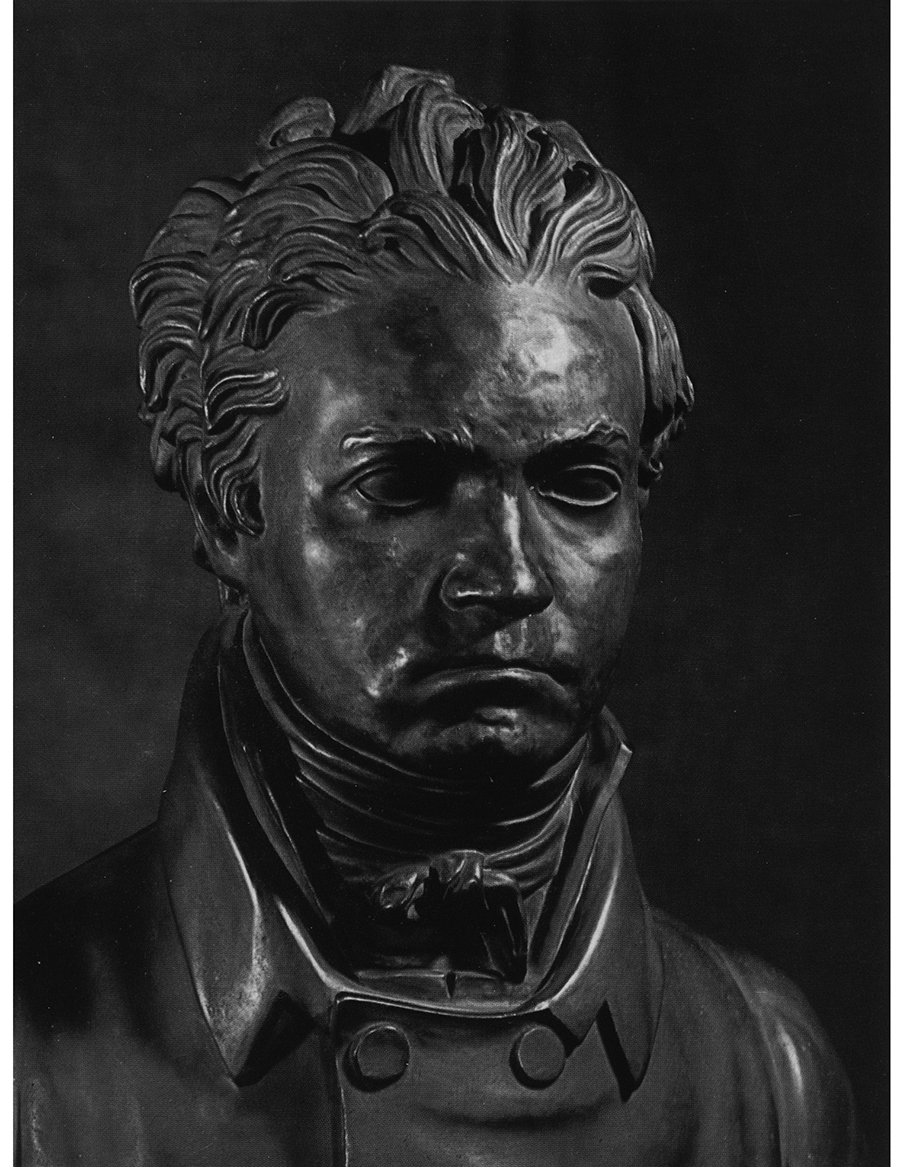

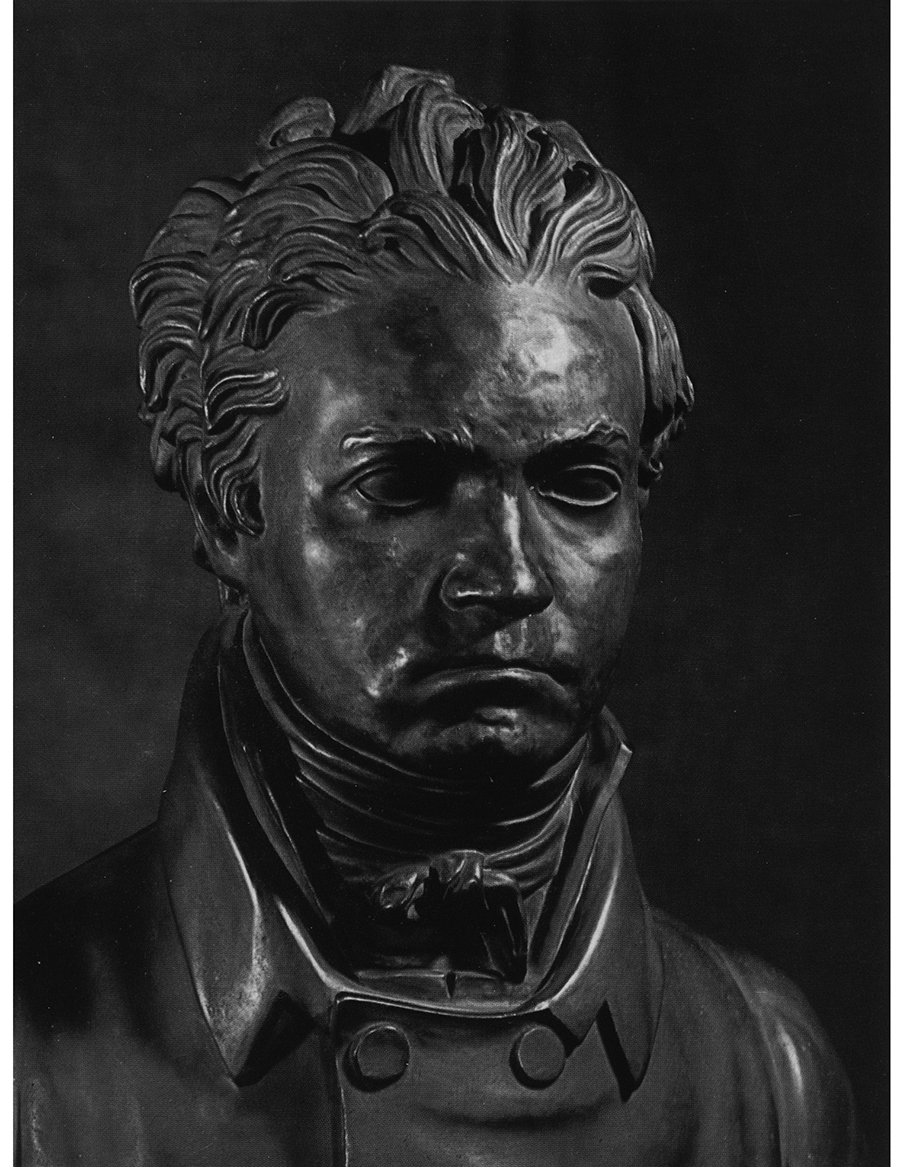

Bust of Beethoven by Franz Klein (1812). Beethoven-Haus, Bonn.

LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN

The Piano Sonatas History Notation Interpretation

JAN MARISSE HUIZING

Translated by

GERALD R. METTAM

Yale UNIVERSITY PRESS

New Haven and London

Published with assistance from the Annie Burr Lewis Fund.

Published with assistance from the Mary Cady Tew Memorial Fund.

Originally published in German. Title of the original German edition: Ludwig van Beethoven: Die Klaviersonaten. Interpretation und Auffhrungspraxis by Jan Marisse Huizing, ED 21349, 2012 Schott Music, Mainz, Germany.

Translation copyright 2021 by Gerald R. Mettam.

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail (U.K. office).

Set in Janson Text type by Newgen North America, Austin, Texas.

Printed in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2021933966

ISBN 978-0-300-25160-9 (paper : alk. paper)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992

(Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Floris and Han

Contents

Preface

WHILE MANY STUDIES OF Beethovens piano sonatas, for example those of Schenker, Tovey, Uhde, Rosen, and many others, concentrate specifically on analytical aspects such as form and harmony, this book has its origins in the need to highlight a number of other, no less important themes.

Questions like the correlation of the musical content and form, knowledge of historical performance practice, and the choice of instrument contribute just as significantly to the insight we can gain into Beethovens piano sonatas.

In addition, for a well-considered interpretation, attention must be paid to the manner in which Beethoven expressed his musical objectives, to his own specific sound-image, his pianism, and the way in which he expressed his intentions in the notation. The significance of Beethovens handwriting along with knowledge of the various editions, from the original printing through to the current urtext, are equally necessary for the creation of a convincing interpretation.

Of course, this book also investigates the playing of great interpreters, both past and present, whereby a historical overview is presented of the many recordings that have been made of Beethovens piano sonatas, including filmed recordings on DVD.

Many of these subjects came to the fore during my years as professor of piano and piano methodology at the Amsterdam Conservatory, where it was my privilege to find a kindred spirit in the person of my colleague, the pianist Willem Brons. Over the years it was an inspiring journey of exchanging discoveries and ideas about Beethoven interpretation, which led to invaluable contributions for this book. Thanks must also go to pianist/organist Christo Lelie for his continuing support and making available to me his extensive library and archive. Also warmly appreciated were interesting suggestions from my colleagues Albert Brussee, fortepianist Bart van Oort, and the Australian pianist Geoffrey Douglas Madge. In addition, I am grateful to the late Frans Schreuder. His substantial archive was of great importance during my research.

After the first edition of this book was published in German by Schott in 2012 (translation from the Dutch by Matthias Mller), further research strengthened my desire to publish an expanded English edition.

In preparing this manuscript, I would like to thank Dr. Silke Bettermann from the Beethoven-Haus in Bonn for her important information, and my sincere thanks go to Bart van Sambeek for editing several music examples. Furthermore, I must express my gratitude to the late eminent concert pianist and scholar Paul Badura-Skoda. His kind comments and advice were of great value in bringing this book to completion.

The task for this English translation was undertaken by Gerald Mettam on the basis of the original expanded Dutch manuscript. This led to an inspiring collaboration for which I am very grateful. In addition, I have to thank Matthias Mller again, who translated quotations from the German, French, and Italian sources insofar as an original source was not already available (see Bibliography). Furthermore, I must express my thanks to Schott and Universal Edition, whose edition of the sonatas I used for the majority of the music examples. Finally, my thanks go to Yale University Press, in particular and in order of appearance: pianist Boris Berman for alerting editor Sarah Miller to the manuscript, language manager Ash Lago, the two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and suggestions, editor Jaya Chatterjee, author Harry Haskell for his expert editing of the manuscript, editorial assistant Eva Skewes, Millie Piekos for excellent proofreading, and senior production editor Joyce Ippolito. They have all been wonderful. I am pleased that this English edition is now available and hope that this book will be a source of inspiration for all those involved with Beethovens piano sonatasas professionals, as amateurs, or, not least, just out of interest in these masterworks.

LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN

CHAPTER ONE

The Sonatas

OverviewForm and Content

You will ask me whence I take my ideas? That I cannot say with any degree of certainty: they come to me uninvited, directly or indirectly. I could almost clasp them in my hands, out in Natures openness, in the woods, during my promenades, in the silence of the night, at earliest dawn. They are roused by moods which in the poets case are transmuted into words, and in mine into tones, that sound, roar and storm until at last they take shape for me as notes.

BEETHOVEN TO LOUIS SCHLSSER, SONNECK (ED.), p. 147

WITH THE COMPOSITION OF his piano sonatas, Beethoven left an oeuvre that since its time has lost nothing of its significance. Beloved by pianists as well as listeners, not only are there the all-too-familiar sonatas such as the Pathtique or the Moonlight, but also the others that continue to inspire anew. Although not every sonata enjoys equal attention from performers or listeners, it is certain that each possesses its own substance and eloquence. From his first sonatas onward, Beethoven presented a musical spectrum from which new horizons are continually revealed. His genial creativity appears to be inextricably bound to his way of constantly finding a new language for each individual sonata and formulating his ideas, not only within each separate movement, but also for the work as a whole. In this first chapter, as an overview, his piano sonatas are briefly discussed, with special attention paid to the connection between form and content, as illustrated by a number of characteristic examples from each sonata.

To begin with, his Sonatas Op. 2 were commended by Beethovens publisher, Artaria, in an advertisement in the Wiener Zeitung of March 9, 1796, in which passing reference is also made to the success of the Piano Trios Op. 1.

Three sonatas for pianoforte by Herr Ludwig van Beethoven. Since this authors previous work, the three piano trios opera 1 of the same, that are already in the hands of the public, have been received with such great approval, one expects likewise from the present work, all the more because, besides the worthiness of the composition, it also has the merit that we can detect in it not only the strength that Herr van Beethoven possesses as a piano player, but also the delicacy with which he treats this instrument.