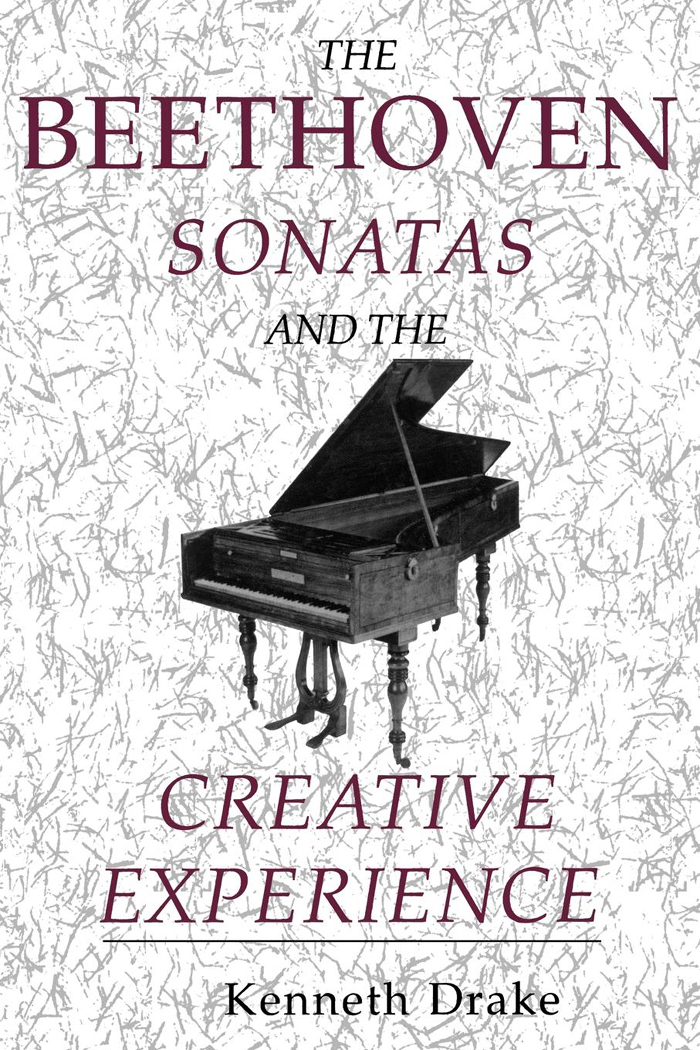

The

Beethoven

Sonatas

and the

Creative

Experience

The

Beethoven

Sonatas

and the

Creative

Experience

Kenneth Drake

INDIANA UNIVERSITY PRESS

BLOOMINGTON & INDIANAPOLIS

This book is a publication of

Indiana University Press

601 North Morton Street

Bloomington, IN 47404-3797 USA

http://www.indiana.edu/~iupress

Telephone orders 800-842-6796

Fax orders 812-855-7931

Orders by e-mail iuporder@indiana.edu

1994 by Kenneth Drake

Index 2000 by Kenneth Drake

First reprinted in paperback in 2000

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The Association of American University Presses Resolution on Permissions constitutes the only exception to this prohibition.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984.

Manufactured in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Drake, Kenneth, pianist.

The Beethoven sonatas and the creative experience / Kenneth Drake. p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-253-31822-X (cloth)

1. Beethoven, Ludwig van, 17701827. Sonatas, piano. 2. Sonatas (Piano)Analysis, appreciation. I. Title.

MT145.B42D7 1994

786.2183092dc20 93-27719

ISBN 0-253-21382-7 (paper)

2 3 4 5 6 05 04 03 02 01 00

To Eskil Randolph,

the indispensable teacher of my youth,

who knew the language of music

and taught it in so unassuming a manner.

C ONTENTS

Preface

It was an afternoon when Stanley Fletcher felt the need for a break before continuing teaching. We were joined by Alexander Ringer, and the conversation turned to the study of applied music. The trouble with you people, he inveighed, is that you teach skills but not what makes the music tick. No doubt Mr. Fletcher agreed in the privacy of his mind.

The desire to become a pianist is sustained by dreams, typically of study with a famous teacher, winning a competition, and playing concerts. Motivation feeds on examples of legendary performers who play throughout the world to critical acclaimpublic relations phrases that never wear out however often they are run through the presses. For this, there is a science of performance to be learned in order that technique and musicianship can be reliably displayed. How else can one hope to reach the final round of the competition, or pass the DMA recital, or even ones recital approval audition? As a consequence, the loftiest model to which one is obliged to aspire becomes the flawless performance on the CD.

The years pass, and the anticipated rewards for years of study may not materialize, leaving a choice between believing in a mirage or believing that life, as Jos Echniz reminded his students, is always more important than playing the piano. Stated another way, it is lifenot the competition prize or the academic degree or rankthat lends significance to the act of making music. Whether a recital in Alice Tully Hall or an afternoon teaching privately in small-town America, the personal fulfillment of giving it away to however few or manythis love of the language of musicconstitutes the real fabric of culture, and culture, we often forget, is not restricted to a geographical location but is taken by the mind wherever it goes. As I think back on those years of study with Mr. Echniz, his attitude toward the profession permeates the basic premise of this writing, that each of us is gifted enough and capable of being the medium for the composers thought.

Understanding the language of music is the skill for which all the musicians other skills must be cultivated. Growing older, to quote Schumann, one should converse more frequently with scores than with virtuosi. The language of a Beethoven sonata is as precise as a legal document; it should not be played without discerning its uniqueness any more than a contract should be signed without understanding every clause. To that end, the players tools are intuition, intelligence, and reflexes that respond to shapes in the score like fingertips reading brailleall coordinated by imagination. Imagination is like an unruly student with unbounded potential, brilliant but easily bored and irregular in class attendance. Once aroused, however, it becomes a tireless detective scrutinizing the score for the clue to what makes the piece tick.

The standards of a degree program, however beneficial the intent, all too often compel conformity instead of fostering independent thought, whether or not the conclusion reached is one the teacher deems correct. Buckminster Fuller addressed the danger in becoming educated, saying that learning is not done with an injection or a pump but by working alongside a loving pioneer while he is still pioneering. Just such a pioneer, Charles Kettering, the inventor of the self-starter and the spray-lacquer finish process in the early days of the automobile, once remarked that he preferred not to work with university-trained assistants; intent upon pursuing an expected result, they frequently failed to notice the unusual along the way. The inventor, he said, may fail hundreds of times before making an important discovery, while, in our educational system, failure normally relegates one to the bottom of the heap. Like the inventor, an interpreter, instead of accepting dictated answers, deals with questions about the inner working of a piece of music, questions that probe far deeper than whether the tone is singing, the runs are clean, and the style is correct.

The present work is not an exercise in musicology or performance practice, nor does it offer measure-by-measure analysis. Instead, it is a work about meaninga personal account of studying, teaching, and playing the Beethoven sonatas, the significance they assume in the innermost self, and, especially, the musical basis for their significance. The immediate purpose is to isolate ideas within the score and to perceive meaning in them and derive meaning from them. Meaning, the personal identification with musical symbols and relationships, is as difficult to measure as the moving air is to see. Nevertheless, like breathing, sensing meaning is divining the spirit within the music, in order to receive it into ones consciousness and be performed by it. Who has not been admonished at some point by a teacher, Dont become so involved? To be performed by the music is to become passionately involved with the relationship between musical symbols and human reasoning, impulses, and emotionsmotivated by inner necessity (to borrow a phrase from Martin Cooper).

In dealing with meaning and the language of music in any period, one should not be deterred by the fact that interpretive choices are always, to a certain extent, subjective. Although determinations of this nature in the pages that follow have been shaped by weighing the evidence, ones understanding has no sooner been formulated in the written word than it is already incomplete. At best, the discussions that are presented may be regarded as a starting point for the readers further reflection and formation of independent judgments.