THE MAHBHRATA PATRILINE

For my family and teachers

The Mahbhrata Patriline

Gender, Culture, and the Royal Hereditary

Simon Pearse Brodbeck

Cardiff University, UK

First published 2009 by Ashgate Publishing

Published 2016 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 2009 Simon Pearse Brodbeck

Simon Pearse Brodbeck has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the author of this work.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Brodbeck, Simon Pearse, 1970

The Mahabharata patriline : gender, culture, and the royal hereditary.

1. Mahabharata - Criticism, interpretation, etc. 2. Patrilineal kinship in the Mahabharata

I. Title

294.5'923048dc22

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Brodbeck, Simon Pearse, 1970

The Mahabharata patriline : gender, culture, and the royal hereditary / Simon Pearse Brodbeck.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-7546-6787-2 (hardcover : alk. paper)

1. Patrilineal kinship in the Mahbhrata. 2. MahbhrataCriticism, interpretation, etc.

I. Title.

BL1138.27.B76 2009

294.5'923046dc22

2009003076

ISBN 9780754667872 (hbk)

This book surveys and discusses the Sanskrit Mahbhrata s central royal patriline which I call the Mahbhrata patriline even though (and partly because) it begins before Bharata and its implications and ramifications within the royal culture that the text imagines, retrojects, and projects. to Four.

What lies before you issued from a research project entitled Epic Constructions: Gender, Myth and Society in the Mahbhrata , which ran from 2004 to 2007 at the School of Oriental and African Studies in Bloomsbury, in association with the Department of the Study of Religions and the Centre for Gender and Religions Research. I thank Julia Leslie who set up the project; Brian Bocking who managed it after her death; the Arts and Humanities Research Board who generously funded it; and all those who participated in and supported the project, discussed my work with me, and assisted this books production in so many ways, most particularly my colleague Brian Black, who read the Mahbhrata with me and commented on the books first full draft, and my co-conspirator San Hawthorne, who has been crucial at every stage.

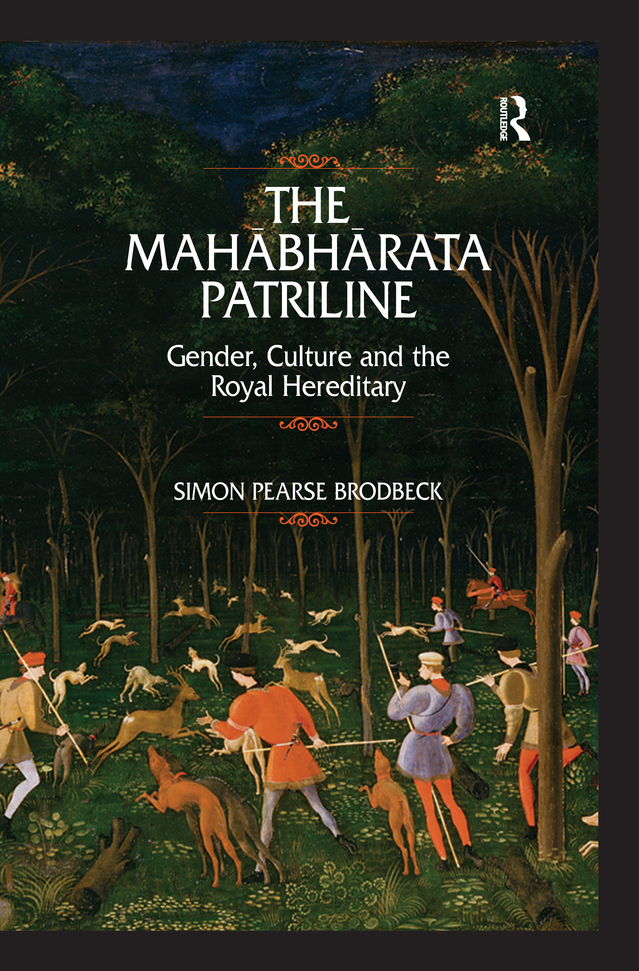

The picture on the cover is reproduced by kind permission of the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford. The lyrics to Welcome to the Machine are reproduced by permission of Roger Waters Music Overseas Ltd (all rights on behalf of Roger Waters Music Overseas Ltd administered by Muziekuitgeverij Artemis B.V.; all rights reserved).

There are many names in this book. The reader is invited to engage with them orally and aurally as well as visually. This pronunciation guide is approximate.

| see | say |

| m a , p a |

| s ee |

| bl ue |

| b ri ck |

| (the same but longer) |

| e | f ey |

| o | go at |

| c | ch eck |

| bar ny ard |

| , | sh oe |

| kh | ba ckh and |

| th | ho th ead |

| (and likewise other aspirated consonants gh, ch, jh, dh, ph, bh) |

| h-plus-half-a-vowel |

Welcome my son, welcome to the machine

Where have you been? Its alright, we know where youve been

Youve been in the pipeline filling in time

Provided with toys and Scouting for Boys

You bought a guitar to punish your ma

You didnt like school and you know youre nobodys fool

So welcome to the machine

Welcome my son, welcome to the machine

What did you dream? Its alright, we told you what to dream

You dreamed of a big star

He played a mean guitar

He always ate in the steak bar

He loved to drive in his Jaguar

So welcome to the machine

(Roger Waters)

Im sure my father felt these things but these are my words, and this is the real lie about my father. I cannot talk about him without talking about myself, just as I can never look at myself in the mirror without seeing his face. These days, when Halloween comes around, I observe the rites and I think about the chosen dead ... but none of them ever comes. Nobody comes but him, the one I dont choose ... He comes to the fire and stands just outside the ring of heat and light ... He has nothing to say to me, he brings no mercy, no forgiveness. He hasnt come to deliver a cryptic message or show me what he has found on the other side. All he is here to say is what he has said already: that we are not so very different, he and I; that, no matter how precious I get about it, a lie is a lie is a lie and I am just as much an invention, just as much a pretence, just as much a lie as he ever was.

(John Burnside 2006:2312)

Part One

A Royal Patrilineal Model

Chapter

Analogical Deceptions

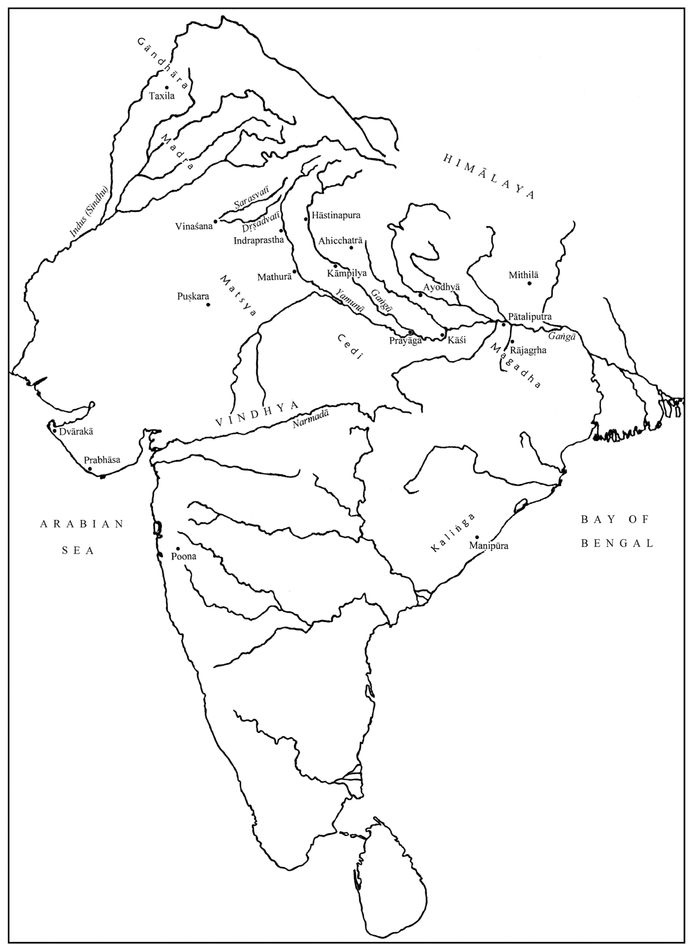

At Poona in western India, for much of the last century, a project team collated the existing Sanskrit Mahbhrata manuscripts and created, through their minute comparison, a reconstituted text (Sukthankar, Belvalkar, Vaidya et al. 193366). The idea was to isolate whatever all the manuscripts have in common. Passages peculiar to individual manuscripts or groups of manuscripts were deemed to be interpolations, and were presented separately from the reconstituted text, as apparatus. When I refer to the Mahbhrata or give references by parvan (book), adhyya (chapter), and loka (verse or prose-unit), I refer to the reconstituted Poona text.

This reconstituted text is hypothesised to approximate the common ancestor of all existing Mahbhrata manuscript traditions.

The names at the bottom denote scripts in which the various regional manuscript traditions keep their Sanskrit Mahbhrata s. The letters in the intermediate generations indicate intermediate versions of the Mahbhrata . For example, is inferred because there are many interpolations that only the Telugu and Grantha manuscripts contain.

This way of conceptualising the development of the Mahbhrata manuscript tradition has its weaknesses. For example, when a manuscript needed copying, it seems that repeatedly, rather than just copying the manuscript, several Mahbhrata manuscripts would be borrowed (sometimes from far afield) and used; so the next generation would contain material from other branches. This process, presumably carried out for purposes of textual enrichment, has traditionally been seen by text-critical scholars in terms of contamination (of one branch via another). If interpolations added in one specific branch of the manuscript tradition are contained only in the direct descendants of that branch, then they can easily be identified as interpolations by the critical editors; but if they are carried widely into other branches, then they may begin to look more and more like elements of an Ur-Mahbhrata. So it is nice to make the assumption that contamination is negligible. The hypothesis that the method reconstructs an ancient text also makes two other assumptions: that scribes would only add to the text, never subtract from it; and that the available manuscripts are representative of the tradition as a whole.