The Wretched of the Earth

OTHER WORKS BY FRANTZ FANON

PUBLISHED BY GROVE PRESS:

Black Skin, White Masks

A Dying Colonialism

Toward the African Revolution

THE WRETCHED

OF THE EARTH

Frantz Fanon

Translated from the French

by Richard Philcox

with commentary by

Jean-Paul Sartre

and

Homi K. Bhabha

Copyright 1963 by Prsence Africaine

English translation copyright 2004 by Richard Philcox

Foreword copyright 2004 by Homi K. Bhabha

Preface copyright 1961 by Jean-Paul Sartre

Originally published in the French language by Francois Maspero diteur, Paris, France, under the title Les damns de la terre, copyright 1961 by Francois Maspero diteur S.A.R.L.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, or the facilitation thereof, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Any members of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use, or publishers who would like to obtain permission to include the work in an anthology, should send their inquiries to Grove/Atlantic, Inc., 841 Broadway, New York, NY 10003.

Published simultaneously in Canada

Printed in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Fanon, Frantz, 1925-1961.

[Damns de la terre. English]

The wretched of the earth / Frantz Fanon ; translated from the French by Richard

Philcox ; introductions by Jean-Paul Sartre and Homi K. Bhabha.

p. cm.

Originally published: Damns de la terre. Paris : F. Maspero, 1961.

ISBN-10: 0-8021-4132-3

ISBN-13: 978-0-8021-4132-3

1. FranceColoniesAfrica. 2. AlgeriaHistory1945-1962. I. Philcox,

Richard. II. Title.

DT33.F313 2004

960.097 1244dc22 2004042476

Grove Press

an imprint of Grove/Atlantic, Inc.

841 Broadway

New York, NY 10003

Distributed by Publishers Group West

www.groveatlantic.com

09 10 11 9 8 7

Contents

III. The Trials and Tribulations

of National Consciousness

Mutual Foundations for National Culture

and Liberation Struggles

From the North Africans Criminal

Impulsiveness to the War of National Liberation

Foreword: Framing Fanon

by Homi K. Bhabha

The colonized, underdeveloped man is a political creature in the most global sense of the term.

Frantz Fanon: The Wretched of the Earth

And once, when Sartre had made some comment, he [Fanon] gave an explanation of his egocentricity: a member of a colonised people must be constantly aware of his position, his image; he is being threatened from all sides; impossible to forget for an instant the need to keep up ones defences.

Simone de Beauvoir, The Force of Circumstance

Frantz Fanons legend in America starts with the story of his death in Washington on December 6, 1961. Despite his reluctance to be treated in that country of lynchers, Fanon was advised that his only chance of survival lay in seeking the leukemia treatment available at the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland. Accompanied by a CIA case officer provided by the American Embassy in Tunis, Fanon flew to Washington, changing planes in Rome, where he met Jean-Paul Sartre but was too enfeebled to utter a single word. A few days later, on October 3, Fanon was admitted to the hospital as Ibrahim Fanon, a supposedly Libyan nom de guerre he had assumed to enter a hospital in Rome after being wounded in Morocco during a mission for the Algerian National Liberation Front.

For my brother Sorab: doctor of my soul; healer of my mind. HKB

His body was stricken, but his fighting days were not quite over; he resisted his death minute by minute, a friend reported from his bedside, as his political opinions and beliefs turned into the delirious fantasies of a mind raging against the dying of the light. His hatred of racist Americans now turned into a distrust of the nursing staff, and he awoke on his last morning, having probably had a blood transfusion through the night, obsessed with the idea that they put me through the washing machine last night.

merely a vain hope? Does such a lofty ideal represent anything more than the lost rhetorical baggage of that daunting quest for a nonaligned postcolonial world inaugurated at the Bandung Conference in 1955. Who can claim that dream now? Who still waits in the antechamber of history? Did Fanons ideas die with the decline and dissolution of the black power movement in America, buried with Steve Biko in South Africa, or were they born again when the Berlin Wall was dismembered and a new South Africa took its place on the worlds stage? Questions, questions....

As we catch the religiosity in Fanons language of revolutionary wraththe last shall be the first, the almighty body of violence rearing up... The legacy of Fanon leaves us with questions; his virtual, verbal presence among us only provokes more questions. And that is as it should be. O my body, make of me always a man who questions! was Fanons final, unfinished prayer at the end of Black Skin, White Masks.

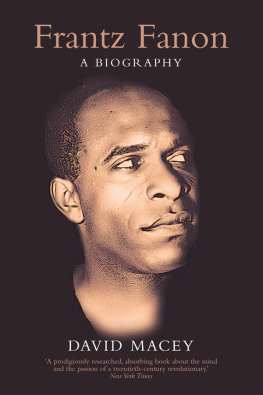

The time is right to reread Fanon, according to David Macey, his most brilliant biographer, because Fanon was angry, and without the basic political instinct of anger there can be no hope for the wretched of the earth [who] are still with us. Fanon writes in The Wretched of the Earth, and it is my purpose, almost half a century later, to ask what might be saved from Fanons ethics and politics of decolonization to help us reflect on globalization in our sense of the term.

It must seem ironic, even absurd at first, to search for associations and intersections between decolonization and globalization parallels would be pushing the analogywhen decolonization had the dream of a Third World of free, postcolonial nations firmly on its horizon, whereas globalization gazes at the nation through the back mirror, as it speeds toward the strategic denationalization of state sovereignty. The global aspirations of Third World national thinking belonged to the internationalist traditions of socialism, Marxism, and humanism, whereas the dominant forces of contemporary globalization tend to subscribe to free-market ideas that enshrine ideologies of neoliberal technocractic elitism. And finally, while it was the primary purpose of decolonization to repossess land and territoriality in order to ensure the security of national polity and global equity, globalization propagates a world made up of virtual transnational domains and wired communities that live vividly through webs and connectivities on line. In what way, then, can the once colonized woman or man become figures of instruction for our global century?

Global duality should be put in the historical context of Fanons founding insight into the geographical configuration of colonial Spatial compartmentalization, Macey acutely argues, is typical of the social structure of settler societies like Algeria, but demographic duality is also found in other colonial societies that were divided between the club and the bazaar or the cantonment and the civil lines. Fanons emphasis on the racialization of inequality does not, of course, apply uniformly to the inequities of contemporary global underdevelopment. However, the racial optic if seen as a symbolic stand-in for other forms of social difference and discrimination does clarify the role played by the obscuring and normalizing discourses of progress and civility, in both East and West, that only tolerate differences they are able to culturally assimilate into their own

Next page