Alessandro Manzoni - The Betrothed

Here you can read online Alessandro Manzoni - The Betrothed full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 1983, publisher: Penguin UK, genre: Art. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Betrothed

- Author:

- Publisher:Penguin UK

- Genre:

- Year:1983

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Betrothed: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Betrothed" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Betrothed — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Betrothed" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

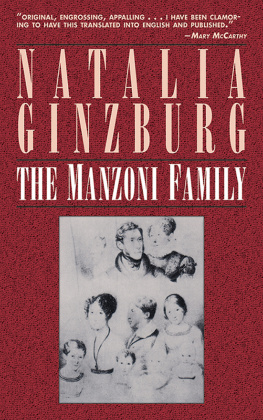

Alessandro Manzoni was born in 1785 on his fathers estate near Lake Como, Italy. From the age of five he was packed off to boarding-school, where his mother never visited him. When he was seven, she left his father and went to live in Paris with a wealthy Milanese liberal. As a young man Manzoni subscribed to the ideals of the French Revolution, and in 1801 he wore a poem which contained harsh anti-Christian views. He joined his mother in Paris in 1805, and in 1808 married Henriette Blondel, a Swiss Protestant girl. The marriage was a very happy one, except for a few tensions over religion which were resolved when they both became practising Catholics. Manzoni took his family to Milan in 1810. The next few years saw the publication of a series of odes, largely on religious subjects. Manzoni also studied Italian history, and wrote several historical plays in verse during the years following 1818. He began work on I Promessi Sposi (The Betrothed) in 1821, and published it in 1827; it was an instant success, and ran to nine editions in four years. Manzoni rewrote the book completely for a definitive, Tuscanized edition, which appeared in 1840 and virtually marked the end of his creative life. He lived another thirty-three years, but they were not particularly happy ones. He had long suffered from a nervous disorder, which now grew worse. Henriette had died in 1833, his second wife also died many years before him, and only two of his nine children survived him. When he died in 1873 he was given a state funeral, and Verdi wrote his famous Requiem for the first anniversary of Manzonis death.

Bruce Penman was a versatile linguist who had a good reading knowledge of ten languages, four of which he spoke fluently. His translation of The Betrothed was awarded a special prize by the Italian Institute of Culture in 1973. He edited Five Italian Renaissance Comedies for Penguin Classics in 1978, and himself translated two of the five plays it contains. In 1984, his translation of China by Gildo Fossati won the John Florio Prize for the best translation from the Italian of the year. His other published translations, from Italian, French and Spanish, include works in the fields of travel, ancient history and oriental art. He was married, with one son and one daughter.

Bruce Penman died in 1986.

Alessandro Manzonis mother was the beautiful and brilliant daughter of Cesare Beccaria, a distinguished writer on penal reform who enjoyed considerable fame not only in his native Lombardy, but also in liberal literary circles in pre-revolutionary Paris. By the time Giulia Beccaria was nineteen she had formed a friendship with Giovanni Verri, a member of another prominent Milanese liberal family, which was compromising for both of them; for Verri was a Knight of Malta and consequently stood to lose both his position and his income if he married. His family, rather than hers, took the initiative in regularizing the situation by marrying her off in 1782 at the age of twenty to someone else. This was Don Pietro Manzoni, a solemn, religious, conservative widower of forty-seven, with estates in the beautiful country near Lake Como which was to be described so well in I Promessi Sposi (The Betrothed). On 7 March 1785 the author was born, and put straight out to nurse. Seven years later his mother left her husband and went off to Paris with Carlo Imbonati, a wealthy Milanese liberal, with whom she lived happily and devotedly until his death. They had considerable social success in literary circles in the French capital.

There has been some controversy about Alessandros true paternity.

Alessandro clearly did not have a happy childhood. After a long time out at nurse and a short time back at home, he had been sent off at the age of five to boarding-school, where his mother never visited him, even before her elopement. A series of boarding-schools followed, none of which he enjoyed, though he studied well and acquired a good knowledge of Latin. His holidays were spent largely on the family estates near Lake Como, and his lasting love for that countryside clearly dates from this period. The unfortunate Don Pietro was probably not very good company for the boy.

Alessandro had several changes of scene during his school-days, owing to political developments. (These were the years when Lombardy was liberated from Austrian rule by French revolutionary forces under Napoleon.) But the education had a strongly ecclesiastical tinge throughout, and Alessandro seems to have been a pious little boy.

As he grew up, however, Alessandro, like many European liberals, fell under the spell of the French Revolution, and of the idea of Napoleon as the great liberator, which survived so many acts of tyranny on his part. After the Battle of Marengo and the Peace of Luneville in 1801, Manzoni wrote a poem entitled Il Trionfo della Libert, which contained some very harsh remarks about Christianity and shows that he cannot have been a believer at that time.

In 1805, when he was twenty, he received a letter from Carlo Imbonati, who was still living with Donna Giulia in Paris, inviting him to come and stay with them. He accepted the invitation, but before he could act on it Imbonati died. Not long afterwards Alessandro joined his mother in Paris and settled into her circle of literary friends. (He had himself already begun to make his mark as a poet.)

Manzonis reunion with his mother, whom he had scarcely seen since early childhood, was a great success. They got on very well now that he was grown up, and this can fairly be called the first period in which he experienced normal human affection. Donna Giulia made rather a cult of her attachment to the memory of Imbonati, in which Alessandro joined her to the extent of celebrating the dead mans virtues in one of his best-known poems. The death of Don Pietro Manzoni in 1807 does not seem to have moved him greatly.

Soon after this Alessandro, or perhaps his mother, began to think that it was time he took a wife. They started by tracking down a girl whom he had admired from afar a few years earlier, but when they found her in Genoa she was already married. Later on they went back to Lombardy, to visit the estate which Imbonati had left to Donna Giulia, and which subsequently became a beloved country retreat for Alessandro. Among Donna Giulias acquaintances in Milan was a Swiss businessman, Louis Blondel, who had had some dealings with Imbonati. Blondels sixteen-year-old daughter Henriette took the fancy of Donna Giulia and Alessandro, and the young couple became engaged.

The Blondels were Protestants, and Alessandro was a Catholic, nominally at least. Henriettes mother was bitterly opposed to the match for that reason, and made trouble both before and after the wedding. But Henriette was kind, gentle, intelligent and affectionate, and made Alessandro an excellent wife. She also got on very well with Donna Giulia.

Alessandro was far from being a convinced Catholic at this period, and he made no objection to a Protestant wedding, which took place in 1808. Six months later he returned to Paris and set up house there together with his wife and mother, and resumed his place in the literary life of the capital.

His first child, a daughter, was born in December of the same year. Should she be baptized as a Catholic or as a Protestant? The first stirrings of his reconversion to the faith were making themselves felt, and he insisted on a Catholic christening, rather to his wifes distress. Shortly afterwards he applied to the pope for the dispensation which is necessary for a mixed marriage according to the Catholic rite, and this ceremony took place in February 1810. A little later husband and wife both embraced the Catholic faith, whole-heartedly and permanently.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Betrothed»

Look at similar books to The Betrothed. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Betrothed and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.