The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

For my parents, Patrick and Patricia Clark, and for my sister, Elizabeth, and for my brother, Aaron

All water has a perfect memory

and is forever trying to get back to where it was.

Toni Morrison, The Site of Memory

I.

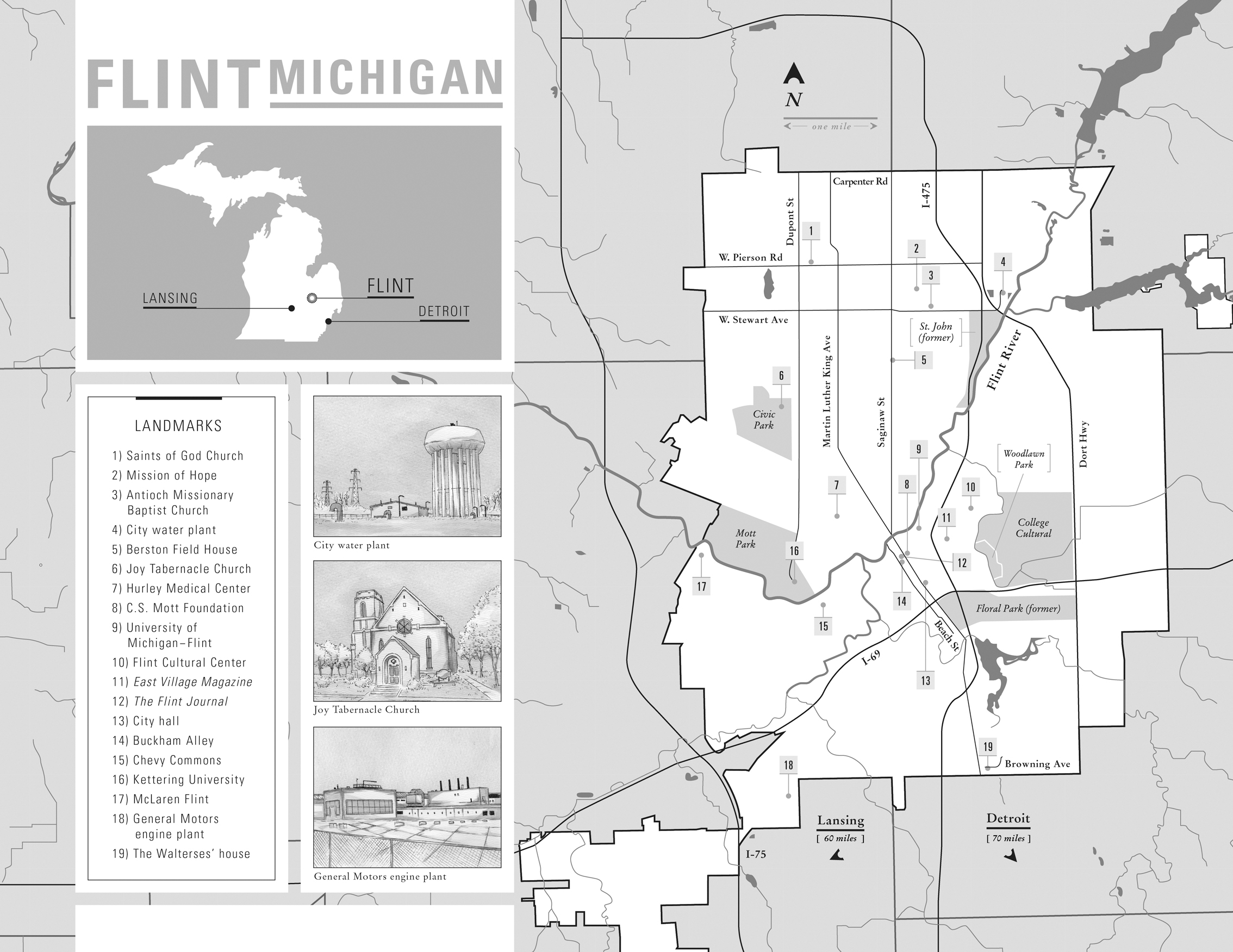

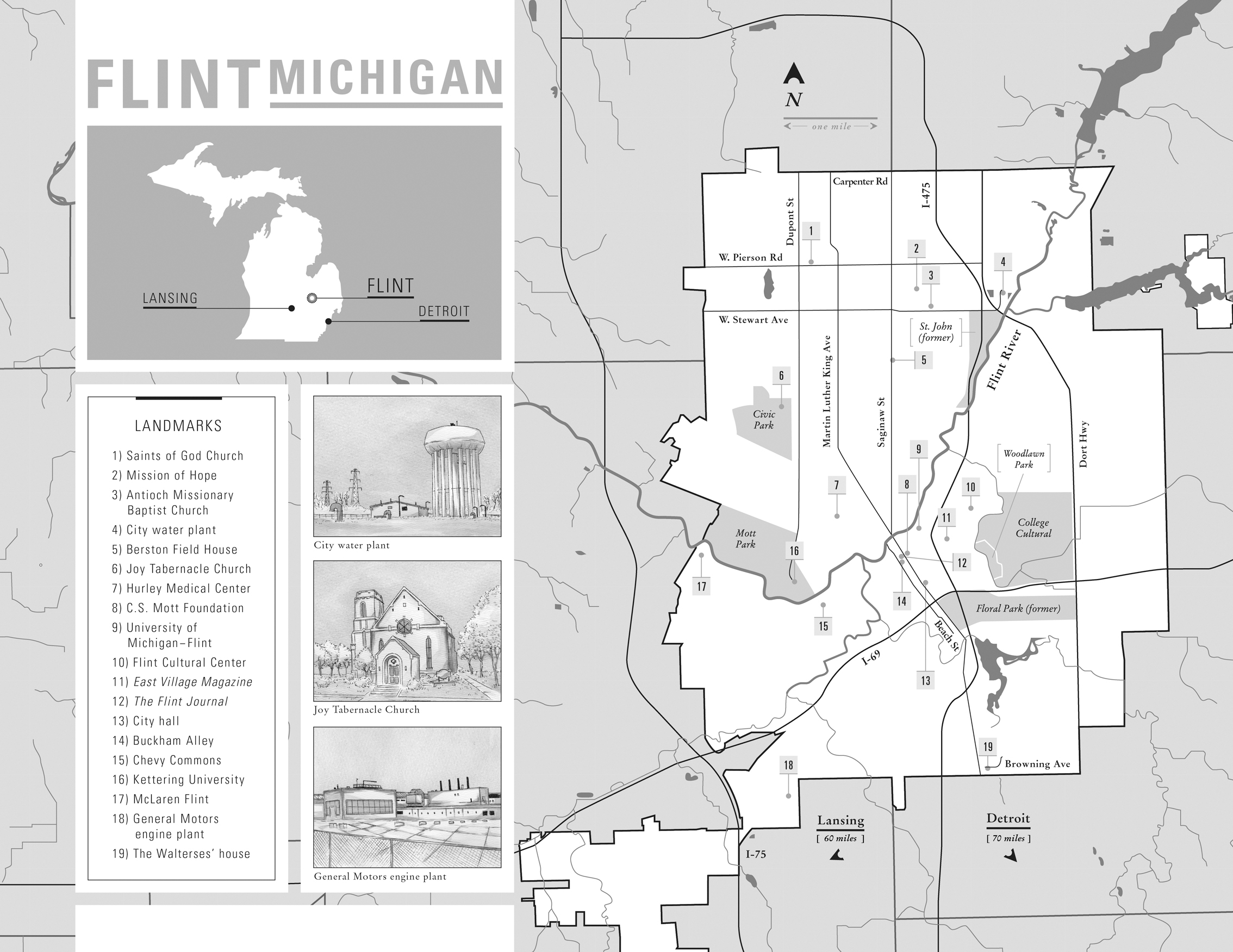

On a hot day in the summer of 2014, in the Civic Park neighborhood where Pastor R. Sherman McCathern preached in Flint, Michigan, water rushed out of a couple of fire hydrants. Puddles formed on the dry grass and splashed the skin of the delighted kids who ran through it. But the spray looked strange. The water was coming out, dark as coffee, for hours, McCathern remembered. The shock of it caught in his throat. Something is wrong here.

Something had been wrong for months. That spring, Flint, under direction from state officials, turned off the drinking water that it had relied upon for nearly fifty years. The city planned to join a new regional system called the Karegnondi Water Authority, and while it waited for the KWA to be built, it began bringing in its water from the Flint River. McCathern didnt pay much attention to the politicking around all this; he had enough to worry about at his busy parish. But after the switch, many of his neighbors grew alarmed at the water that flowed from their kitchen faucets and shower heads. They packed public meetings, wrote questioning letters, and protested at city hall. They filled clear plastic bottles from their taps to show how the water looked brown, or orange, and sometimes had particulates floating in it. Showering seemed to be connected with skin rashes and hair loss. The water smelled foul. A sip of it put the taste of a cold metal coin on your tongue.

But the authorities said everything was all right and you could drink it, so people did, McCathern said later. Residents were advised to run their faucets for a few minutes before using the water to get a clean flow. As the months went by, the city plant tinkered with treatment and issued a few boil-water advisories. State environmental officials said again and again that there was nothing to worry about. The water was fine.

Whatever their senses told them, whatever the whispers around town, whatever Flints troubled history with powerful institutions telling them what was best for them, this wasnt actually hard for people like McCathern to believe. Public water systems are one of this countrys most heroic accomplishments, a feat so successful that it is almost invisible. By making it a commonplace for clean water to be delivered to homes, businesses, and schools, we have saved untold lives from what today sound like antiquated diseases in a Charles Dickens novel: cholera, dysentery, typhoid fever. Here in Flint, it was instrumental in turning General Motorsfounded in 1908 in Vehicle City, as the town was knowninto a global economic giant. The advancing underground network of pipes defined the growing city and its metropolitan region, which boasted of being home to one of the strongest middle classes in the country.

McCathern is a tall, bald man with a thin mustache and a scratchy rasp in his baritone voice. At the time of the water switch, he had led the nondenominational Joy Tabernacle Church for about fifteen years. It was founded in the YWCA in downtown Flint, where it held baptisms in the swimming pool. But in 2009, it made a home in Civic Park, when a Presbyterian church closed after eighty-five years and gave its sanctuary over to the young and hopeful congregation.

By then, Civic Park, one of Americas oldest subdivisions, was a desert of deserted historically significant homes, the pastor said. Built between 1917 and 1919 by General Motors and DuPont and Company along curving, tree-lined boulevards, the tidy houses were designed for Flints autoworkers and their families. In the end, people just want to be seen.

The ghosts of the past went well beyond Civic Park. Between General Motors and the United Auto Workers (which won the right to collectively bargain in Flints sit-down strike in the 1930s), the city had been a flourishing hub for American innovation.

Away from the assembly lines and the executive suites, the people of Flint felt that the city shouldnt just be a place to work; it should also be a place to thrive. Charles Stewart Mott, an auto pioneer who became GMs largest single stockholder and a three-term mayor, created a nationally renowned community schools program that provided education, skills-building workshops, and social services. (His influence is still felt through the C. S. Mott Foundation, a philanthropic power broker headquartered in the city.) The Parks Department had a robust Forestry Division that cultivated a beautiful thicket of willow, oak, and elm trees along the avenues. The Michigan School for the Deaf expanded into new buildings that served hundreds of students from around the state. And on a green campus just east of downtown, the city invested in its cultural life by developing the Flint Symphony Orchestra, as well as a state-of-the-art stage and auditorium, schools for both the performing arts and visual arts, a youth theater, a sunny public library, museums of local history and classic cars, the largest planetarium in the state, and the sweeping Flint Institute of Arts, which lined its galleries with everything from Matisse paintings to Lichtenstein silk screens to carved African masks.

But in the latter part of the twentieth century, GM closed most of its plants in the city and eliminated almost all the local auto jobs.

With so much lost, Flint needed help. An emergency plan. A large-scale intervention of some kind. But not only was there no hope of a bailoutof the kind given to the auto industry and Wall Street banks in 2008 and 2009the State of Michigan exacerbated Flints woes by dramatically reducing the money that it funneled to its cities. In a practice called revenue sharing, the state redistributes a portion of the money it collects in sales taxes to local governments. That plus property taxes are what cities use to pay for public services. But between 1998 and 2016, Michigan diverted more than $5.5 billion that would ordinarily go to places such as Flint to power streetlights, mow parks, and plow snow. Instead, the state used the money to plug holes in its own budget. This was highly unusual. As Michigan made cuts, forty-five other states managed to increase revenue sharing to their cities by an average of 48 percent, despite a national economic downturn that affected everyone. Among the five states where revenue sharing declined, Michigan slashed more than any other, by far. For Flint, this translated into a loss of about $55 million between 2002 and 2014. That amount would have been more than enough to eliminate the citys deficit, pay off its debt, and still have a surplus. But the money never came, and, at the same time, Flint was thumped with the Great Recession, the mortgage crisis, a major restructuring of the auto industry, and a crippling drop in tax revenue.

If you wanted to kill a city, that is the recipe. And yet Flint was very much alive. In 2014, the year of the switch to a new source of drinking water, it was the seventh-largest city in the state. On weekdays, its population swelled as people commuted into town for work in the county government, the regions major medical centers, four college campuses, and other economic anchors. For all the empty space, teens in shining dresses still posed for prom photos in the middle of Saginaw Street, the bumpy brick road that is Flints main thoroughfare. Parents still led their children by the hand into the public library for Saturday story time. Older gentlemen lingered at the counter of one of Flints ubiquitous Coney Island diners, and the waitresses at Grandmas Kitchen on Richfield Road kept the coffee flowing. For about ninety-nine thousand people, Flint was home.

Next page