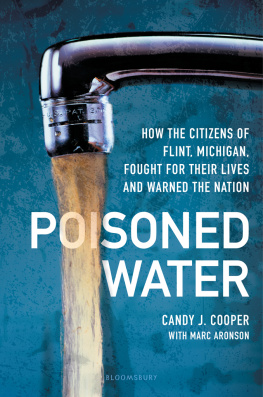

BLOOMSBURY CHILDRENS BOOKS

Bloomsbury Publishing Inc., part of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

1385 Broadway, New York, NY 10018

BLOOMSBURY, BLOOMSBURY CHILDRENS BOOKS, and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

First published in the United States of America in May 2020

by Bloomsbury Childrens Books

Text copyright 2020 by Candy J. Cooper and Marc Aronson

This electronic edition published in 2020 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

All rights reserved

You may not copy, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (including without limitation electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, printing, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc does not have any control over, or responsibility for, any third-party websites referred to or in this book. All internet addresses given in this book were correct at the time of going to press. The author and publisher regret any inconvenience caused if addresses have changed or sites.

Bloomsbury books may be purchased for business or promotional use. For information on bulk purchases please contact Macmillan Corporate and Premium Sales Department at

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Cooper, Candy J., author. | Aronson, Marc, author.

Title: Poisoned water / by Candy J. Cooper and Marc Aronson.

Description: New York : Bloomsbury Childrens Books, 2020.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019045874 (print) | LCCN 2019045875 (e-book)

ISBN: 978-1-5476-0232-2 (HB)

ISBN: 978-1-5476-0233-9 (eBook)

Subjects: LCSH: Lead poisoningMichiganFlintJuvenile literature. | Drinking waterLead contentMichiganFlintJuvenile literature. | Water quality managementMichigan FlintJuvenile literature. | Flint (Mich.)History21st centuryJuvenile literature. Classification: LCC RA1231.L4 .C58 2020 (print) | LCC RA1231.L4 (e-book) | DDC 615.9/25688dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov /2019045874

LC e-book record available at https://lccn.loc.gov /2019045875

Book design by John Candell

To find out more about our authors and their books please visit www.bloomsbury.com where you will find extracts, author interviews and details of forthcoming events, and to be the first to hear about latest releases and special offers, sign up for our newsletters.

To the raised voices and young people of Flint

C. C.

To the people of Flint, and to librarians such as Cindy and Lynn, who make sure young people have access to the true stories of our, of their, time.

M. A.

INCUBATION

It is 2016 and the City of Flint says,

Dont boil the water

I return to the city for the first time

since the story surfaced. Riding through the hood,

crossing at the corner of Pierson and Dupont,

stands a string of neon stanchions,

military servicemen, a gaggle of palettes,

a gaggle of bottled waters wishing us well.

My boy posts a picture of his back

bubbling with fissures in an even spread

having bathed in the citys northeast waters,

the contagion carries itself into the host,

bearing witness to a feast of skin

and other soft metals.

Jonah Mixon-Webster

Contents

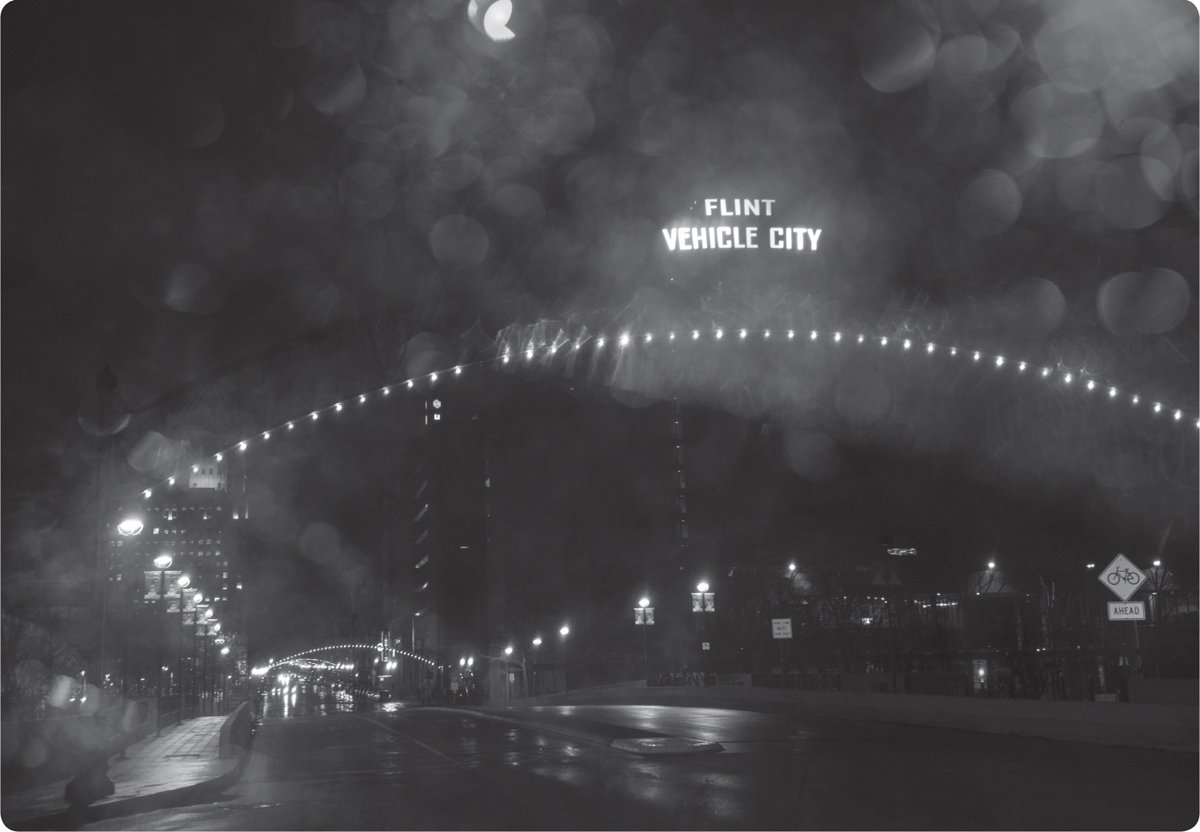

Flint is called Vehicle City because it thrived as a center for building horse-drawn buggies in the late 1800s. Horseless carriages, or cars, soon followed.

Prologue

A t Flint Odyssey House on a clear October morning more than four years after the Flint, Michigan, water crisis began, a few members of an organization of community groups have gathered for their monthly meeting. I am there to make a presentation as a visiting researcher.

The group, Community Based Organization Partners, brings together smaller health-related nonprofits in Flint to recognize and advocate for the community as an entity to be reckoned with all by itself, like a hospital or a university. The group includes academics, social workers, and clergy, and together they act as unofficial gatekeepers of outside research to be done in Flint, establishing their own community ethics review board. The matriarch of the group, E. Hill DeLoney, has specialized throughout a long activist career in advancing the health and well-being of black youth. DeLoney has spoken publicly a few times about the water crisis, once in 2016 when she sat on a University of Michigan health policy panel. There she described a parallel crisis that ran right alongside the disaster of Flints poisoned water: an epidemic of mistrust. Flint residents trustin elected officials, government workers, scientists, journalists, and researchers of all kindssounded as fragile as the shell of an egg. We need to understand that trust is very hard to get in the first placevery, very hard, DeLoney said on the panel. But it can dissipate in a matter of seconds.

Flint hadnt started out with very much trust at all. But when [the water crisis] happened, I cannot tell you how deeply mistrust almost became a cancer in our community. We dont trust anything they tell us, and its going to be a long time [before we do].

On this fall morning in late 2018, the esteemed DeLoney has had to leave unexpectedly due to a health emergency in her family. In her absence, two members of the group, Sarah Bailey and Luther Evans, preside. At least four more people have phoned in, including a pastor, a public health researcher, and Don Vereen, the director of community-based public health at the University of Michigan School of Public Health. Their voices rise out of a console telephone on the table.

I am there to describe the book I am hoping to write and to ask for the groups help. I am a native of Michigan and have worked and studied in the state, but I am aware of my Flint outsider status. The room is very quiet.

The woman to my left, Elder Bailey, is a lifelong Flint resident, a church pastor, a community health advocate, and an expert on acute care for stroke victims. I have heard her speak on a panel about the underlying social determinants of the water crisis, where she described the waters effects on her family, her friends, and her own health after she spent eight days in intensive care with a severe cough. Today she wears a jacket, her hair upswept in neat cornrows.

I am aware that race is the elephant in the room, as DeLoney has often said. She says it is in the water crisis room and in the room of America. I know that Flint is highly segregated by race and income level. I am white and Bailey, Evans, and DeLoney are black.

But I also know that water harmed everyone in Flint, not just one group or one house or one neighborhood. It harmed people who worked in Flint and lived outside of Flint. And the crisis inspired a comingling of racial, ethnic, religious, and income groups working together. Flint has a very strong community spiritedness that arises especially in moments of struggle, most famously during the brutal Flint Sit-Down Strike of 19361937, which led to the consolidation of the United Automobile Workers, the unionization of the US automobile industry, and the conditions that would help build the American middle class during the coming years.