Books by Frithjof schuon

The Transcendent Unity of Religions

Spiritual Perspectives and Human Facts

Gnosis: Divine Wisdom

Language of the Self

Stations of Wisdom

Understanding Islam

Light on the Ancient Worlds

In the Tracks of Buddhism

Treasures of Buddhism

Logic and Transcendence

Esoterism as Principle and as Way

Castes and Races

Sufism: Veil and Quintessence

From the Divine to the Human

Christianity/Islam: Essays on Esoteric Ecumenicism

Survey of Metaphysics and Esoterism

In the Face of the Absolute

The Feathered Sun: Plains Indians in Art and Philosophy

To Have a Center

Roots of the Human Condition

Images of Primordial and Mystic Beauty: Paintings by Frithjof Schuon

Echoes of Perennial Wisdom

The Play of Masks

The Transfiguration of Man

The Eye of the Heart

Form and Substance in the Religions

Edited Writings of Frithjof Schuon

The Essential Writings of Frithjof Schuon, ed. Seyyed Hossein Nasr

The Fullness of God: Frithjof Schuon on Christianity, ed. James S. Cutsinger

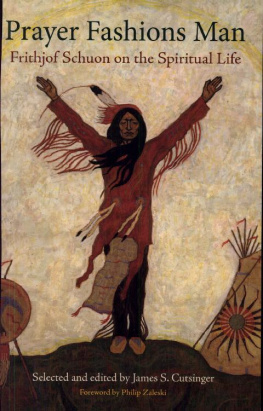

Prayer Fashions Man: Frithjof Schuon on the Spiritual Life, ed. James S. Cutsinger

Art from the Sacred to the Profane: East and West, ed. Catherine Schuon

Poetry by Frithjof Schuon

The Garland

Road to the Heart: Poems

Songs for a Spiritual Traveler: Selected Poems

Adastra & Stella Maris: Poems by Frithjof Schuon

Autumn Leaves &The Ring: Poems by Frithjof Schuon

Songs without Names: Volumes I-VI

Songs without Names: Volumes VII-XII

World Wheel: Volumes I-III

World Wheel: Volumes IV-VII

Biographical Notes

Catherine Schuon was born on August 13, 1924 in Bern, Switzerland. As the daughter of a career Swiss diplomat she was exposed to many cultures, spending her early school years in pre-war Berlin and then in Algiers, where she learned French and came to love North-African culture. She returned to Switzerland during World War II, where she studied languages and helped to care for refugee children. Just as World War II ended she joined her father, who had been named Swiss Ambassador to Argentina. While in Argentina she learned Spanish and developed her gift for painting. Having no affinity with the diplomatic life, she returned to Switzerland where she worked with Italian artists.

Her interest in world religions and spirituality brought her into contact with Frithjof Schuon, whom she married in May 1949. She accompanied her husband on all of his travels and helped him to receive visitors and answer correspondence from spiritual seekers, which brought her into contact with people from diverse religions and from across the world. She became fluent in English and conversant in Italian, in addition to the three languages of her youth: German, French, and Spanish. Along with her husband, she was adopted into the Sioux and Crow tribes.

The Schuons lived near Lake Geneva until 1980 when they moved to the United States and established themselves in the forests of Indiana. Since her husband's death in 1998 Mrs. Schuon spends several months each year traveling throughout the world to visit many of Frithjof Schuon's admirers, each time returning to the serenity of her home in the woods outside of Bloomington, Indiana.

Keith Critchlow is Professor Emeritus at the Prince of Wales Foundation in London and co-founder of the Te-menos Academy. He was a former professor of Islamic art at the Royal College of Art and Founder Member of the Research into Lost Knowledge Organization. An internationally known lecturer on Islamic Art, he is the author of books on geometry, anthropology, the principles of Islamic design, and the Neolithic origins of architecture, including Pythagorean Geometry, Islamic Patterns: An Analytical and Cosmologi-cal Approach, Order in Space, and Time Stands Still: New Light on MegalithicScience.

Barbara Perry was born on April 9, 1923 in Boston, Massachusetts, from old New England ancestry. Her father, Lauriston Ward, a "Boston Brahmin," was an anthropologist who taught at Harvard.

Barbara attended first Vassar, then Sarah Lawrence colleges, at the second concentrating in writing both poetry and prose under the tutorship of Maxwell Geismar,the New York literary critic. Later she met and married Whitall Perryauthor of the opus A Treasury ofTraditional Wisdom.

Meeting Whitall Perry spurred a joint interest in Eastern spirituality. They met the celebrated Orientalist, Ananda Coomaraswamy in New York, which inspired a venture East in search of a spiritual master. On their way to India, visa delays obliged them to stay in Cairo where they met the French luminary and metaphysician Rene Guenon, as well as the English Islamist and poet, Martin Lings, a meeting that in the case of the latter would turn into a lifelong friendship.

Settling in Egypt, in a home next to the Pyramids, the Perrys would summer in Switzerland; there they met the great metaphysician and foremost spokesman of the Sophia Perennis , Frithjof Schuon. Later, political unrest in Egypt forced the Perrys to move to Switzerland where they, along with their children Mark and Catherine, became next-door neighbors of the Schuons, a relationship and proximity that endured forty-six years until Schuon's death in 1998. They also undertook a number of important journeys with the Schuons across Europe, Turkey, Morocco, and the American West where the Schuons and Perrys established special bonds with members of the Sioux and Crow tribes. In 1963 Whitall and Barbara received Indian names from Benjamin Black Elk, the son of the famous Sioux medicine man.

Today Barbara, widowed in November of2005, lives quietly in a retirement community in Bloomington, Indiana.

Principles and Criteria of Art

The fundamental importance of art both in the life of a collectivity and in the contemplative life, arises from the fact that man is himself "made in the image of God": only man is such a direct image, in the sense that his form is an "axial" and "ascendant" perfection and his content a totality. Man by his theomorphism is at the same time a work of art and also an artist; a work of art because he is an "image," and an artist because this image is that of the divine Artist. Man alone among earthly beings can think, speak, and produce works; only he can contemplate and realize the Infinite. Human art, like divine Art, includes both determinate and indeterminate aspects, aspects of necessity and of freedom, of rigor and of joy.

Shiva Nataraja, Lord of the Dance, South India, 10th century

This cosmic polarity enables us to establish a primary distinction, namely the distinction between sacred and profane art: in sacred art what takes precedence over everything else is the content and use of the work; whereas in profane art these are but a pretext for the joys of creation. If within the framework of a traditional civilization art doubtless is never wholly profane, it may however become relatively so precisely because its motive force is to be found less in symbolism than in the creative instinct; such art is thus profane through the absence of a sacred subject or a spiritual symbolism but traditional through the formal discipline that governs its style.1