About the book

Rupi birthed her eldest son squatting in the middle of a paddy field, shin-deep in mud and slush. Soon after, Gurubari, her rival in love, gave her an illness that was like the alakjari vine which engulfs the tallest, greenest trees of the forest and sucks their hearts out. Now Rupi, once the strongest woman in her village, lives out her days on a cot in the backyard, and her life dissolves into incomprehensible ruin around her.

The Mysterious Ailment of Rupi Baskey is the story of the Baskeysthe patriarch Somai; his alcoholic, irrepressible daughter Putki; Khorda, Putkis devout, upright husband, and their sons Sido and Doso; and Sidos wife Rupi. Equally, the novel is about Kadamdihi, the Santhal village in Jharkhand in which the Baskeys live. For it is in full view of the village that the various large and small dramas of the Baskeyss lives play out, even as the village cheers them on, finds fault with them, prays for them and, most of all, enjoys the spectacle they provide.

An astonishingly assured and original debut, The Mysterious Ailment of Rupi Baskey brings to vivid life a village, its people, and the godsgood and badwho influence them. Through their intersecting lives, it explores the age-old notions of good and evil and the murky ways in which the heart and the mind work.

About the author

Hansda Sowvendra Shekhar is a medical officer with the government of Jharkhand. His stories and articles have been published in Indian Literature, The Statesman, The Asian Age, Good Housekeeping, Northeast Review, The Four Quarters Magazine, Alchemy: The Tranquebar Book of Erotic Stories II and The Times of India .

The Mysterious Ailment of Rupi Baskey is his first novel

ALEPH BOOK COMPANY

An independent publishing firm

promoted by Rupa Publications India

This digital edition published in 2013

First published in India in 2013 by

Aleph Book Company

7/16 Ansari Road, Daryaganj

New Delhi 110 002

Copyright Hansda Sowvendra Shekhar 2013

No part of this publication may be reproduced, transmitted, or stored in a retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic, mechanical, print reproduction, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of Aleph Book Company. Any unauthorized distribution of this e-book may be considered a direct infringement of copyright and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

e-ISBN: 978-93-83064-64-9

All rights reserved.

This e-book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated, without the publishers prior consent, in any form or cover other than that in which it is published.

Marang-Buru hirla, Jaher-Ayo hirla

Bonga-Buru ar Hapram-ko lagid,

ar Baba-Bo-Biti lagid

Contents

~

The Strongest Woman of Kadamdihi

Rupi Baskey cannot believe she was once the strongest woman in Kadamdihi, who bore her eldest squatting in the middle of a rice paddy, shin-deep in slush.

This happened in Ashadh, in the middle of the planting season. At the time, Rupi had been in the fields with the other women, transplanting rice saplings. Her sari and petticoat were hitched up to her thigh and there were generous splashes of mud on both. Her hair had come loose over her face and, in pushing it back, she had put streaks of mud on her cheeks and forehead.

Though Rupi was not as big as she should have been at the end of a full term, her belly was quite rounded. And as she was heftily built, the duration of gestation, too, was hard to reckon. Rupi had herself been unsure, as she had never been trained in the ways of motherhood by either her mother or her mother-in-law. She only knew that she would be with child the day her husband touched her. And once she conceived, her monthly bleeding would stop. Since her knowledge was so scanty, Rupi could hardly be blamed for not knowing when she conceived. So, by the time she realized that her monthlies had ceased, the hardness in Rupis belly had risen almost up to her navel. Then Gurubari, who had a daughter of her own, estimated that Rupi had been with child for four or five months and recommended that she visit a dhai-budhi.

Fifth, the midwife had declared on her very first visit.

After the dhai-budhis declaration, Rupi had begun to count down the days to her confinement. She had not returned to Nitrawhere she and Sido stayed and where he had, in all likelihood, touched her in the conceiving waybut stayed on in Kadamdihi and enjoyed the benefits of being a mother-in-waiting, but only as far as her nature allowed her to do so.

~

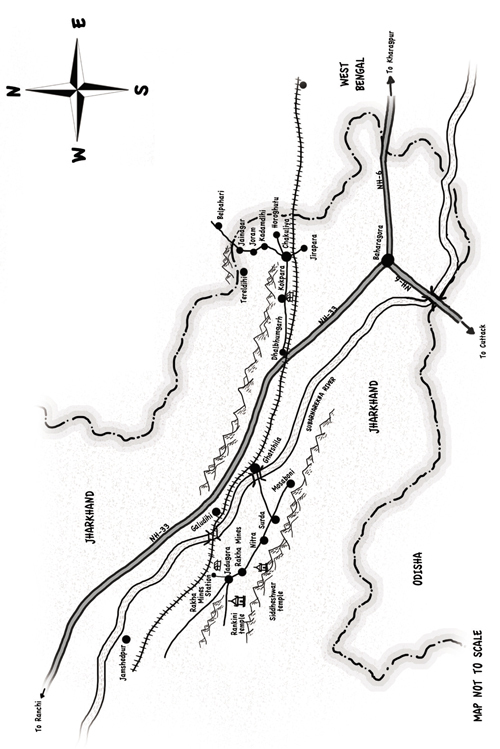

Rupi was from Tereldihi, a village in the hills. She had grown up hunting sparrows with slingshots even as she performed the routine tasks expected of any girl in a village. She cleaned the house, washed utensils and clothes, and drew water from the well. She threw grains to the fowl and grazed the cattle and goats. She helped raise her younger siblings and cousins. She went shopping at the weekly haat in the neighbouring village of Joram, some seven kilometres from Tereldihi. Every month, she joined other girls and boys as they walked to the ration depot in Jainagar, a village at the base of the hills, and carried home bags of sugar and canisters of kerosene. In Jainagar, she attended the annual Buru-Bongathe Worship of the Hillheld on the first Saturday of Ashadh. On some days, she visited the ancient shrine to Marang-Buru on top of the hill. She also never missed the annual Baraghat-pata. Besides all this, Rupi worked the familys fields.

After Rupi was married to Sido and brought to Kadamdihi in the plains, her life had become easier, but only just.

~

Any doctor, had she visited one, would have advised Rupi rest and proper nutrition. Food, she had in plenty. For lunch and dinner she ate rice with vegetables of all kinds: brinjal, potato, kundri, saaru; arak-kohra made from several kinds of greens; crescents of onions, tomatoes, green chillies and salt. Occassionally, there was fish, chicken, even pigeon meat. For breakfast she ate bowls of puffed-rice khajari or beaten-rice taaben soaked in water and mixed with sugar, and a tall glass of tea.

While she had adequate nutrition, Rupi knew no rest. She had to be doing something or the other all the time. If she was not sweeping the racha, she would be cutting firewood. Or she would be boiling all the dirty quilts of the household in water and washing soda. The only pause Rupi made in her labours was a daily ritual. She would sit at a pond, scrub herself clean with a smooth, egg-shaped stone, and then wash dirty clothes with the famed Bottle-brand soap of Chakuliya.

Sido would come home from Nitra every Saturday. He would bring, along with the occasional sweets and clothes, best wishes from Bairam and Gurubari. Over the weekend he would travel to nearby villages with his younger brother, Doso, hiring labourers to work in their fields. Before leaving for Nitra, Sido would repeat to both Doso and Khorda, his father, his standing instruction to not let his pregnant wife perform any physical labour. However, once Sido left, both Khorda and Doso would forget his instruction and the entire family would collectively get down to the business of planting rice.