Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

Copyright 2022 by Shen Fuyu

Translation copyright 2022 by Jeremy Tiang

Originally published in the Chinese language as Jiangren by Insight Media, China South Publishing & Media Group, 2015.

Socit purui de diffusion culturelle de Shanghai / ditions de la Dmocratie et de la Construction (Pkin) - 2015

ditions Albin Michel - Paris 2018

All rights reserved. Copying or digitizing this book for storage, display, or distribution in any other medium is strictly prohibited.

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, please contact permissions@astrahouse.com.

Astra House

A Division of Astra Publishing House

astrahouse.com

Publishers Cataloging-in-Publication data

Names: Fuyu, Shen, author. | Tiang, Jeremy, translator.

Title: The artisans : a vanishing Chinese village / Shen Fuyu; translated by Jeremy Tiang.

Description: New York, NY: Astra House, 2022.

Identifiers: LCCN: 2021917170 | ISBN: 9781662600753 (hardcover) | 9781662600760 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH ArtisansChinaJiangsu ShengHistory. | ArtisansChina. | Handicraft industriesChina. | ChinaSocial life and customs. | BISAC HISTORY / Asia / China | SOCIAL SCIENCE / Customs & Traditions | SOCIAL SCIENCE / Ethnic Studies / Asian Studies

Classification: LCC HD2346.C6 .F89 2022 | DDC 745.5/.0951dc23

First edition

Design by Richard Oriolo

The text and titles are set in GaramondPro-Regular.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

F ROM WHEN I WAS BORN, my family and I lived in a close-knit society. The people I knew in my hometown were either relatives or nearby neighbors, with several generations of affection between us. Its not like everything was sunshine and rainbowswe had misunderstandings and quarrels, and sometimes even came to blows. Still, we knew each other well enough that these never developed into lasting grudges. For several centuries, rules were formed around customs, ways of thinking and agreements, so although the village grew larger and larger, there was peace despite its many disputes.

My hometown is crisscrossing rows of white walls with dark roof tiles. It is ripples swaying through the wheat when the wind blows. It is the fallen ginkgo leaves that cover the ground. Im middle-aged now, and have traveled from my village to the big city, from China to countries thousands of miles away, and though Ive stayed in many places, none of them have made me feel as at ease as my hometown. Where I come from, people speak in loud voices with thick country accents, and their behavior is coarse. All these things are now dear to me, although they once filled me with loathing. As a young man, these signifiers of village life made me ashamed, and all I wanted was to free myself of them.

Until I turned eighteen, I couldnt stand what seemed to me like a dark future in the village. My father was obsessed with not losing face, and the non-stop stream of sarcastic remarks he directed at me were particularly hurtful. When I left the village, I was determined never to return. Now, though, I have gained some empathy. I return to my hometown so my father doesnt lose face, or for the New Year, or even for the birth anniversary of some long-departed ancestor. Even though Ive been going back more often, the swift decay of the village still shocks me. There are no longer any young people there, not even children. Virtually every time I return, I see a newly added grave. Along with the declining population, one old house after another falls into disrepair and then disappears. What used to be farmland is becoming occupied by the factories of the encroaching city. My hometown is no longer my hometown.

Waves of anguish wash over me. Ive realized that this is how hometowns workthe more energy you expend in getting away, the greater the force that pulls you back. And yet the road back has become overgrown with the weeds of time, and can no longer be seen.

When our hometowns vanish, we become rootless people, individual atoms existing in isolation within the ice-cold city. We who left our hometowns have nothing to rely on, and are anxiously absorbed by the prosperity of urban life. Surrounding us are the faces of familiar strangers.

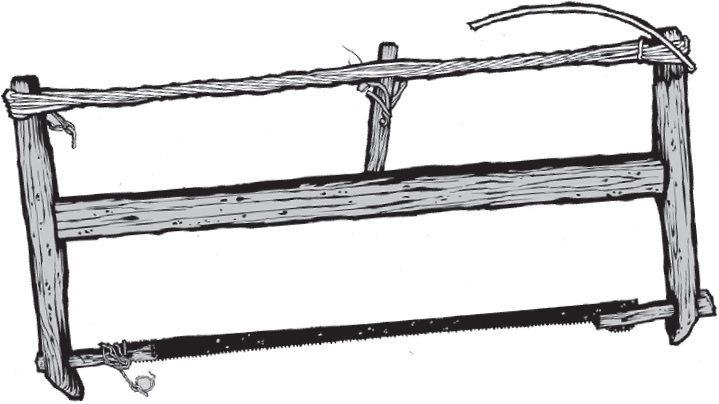

Yes, I know that all around me are lost souls, drifting by as lonely and solitary as I am. We have shared memories. In these recollections are the people we were close to in our hometowns, once so full of life. We knew them as the carpenter, the gardener, the barber, the bricklayer, and so on. Apart from being artisans, all of them were also farmers. And now, the farmers are gone too.

This memoir only goes back a hundred years, the limit of my fathers and grandfathers memories. The people they described to me, as well as the ones Ive known, are mostly gone now. They exist only in family records, just a line or two each.

And yet each person, no matter how humble, contains an epic poem of their own. These villagers may be unknown to the wider world, but they reflect a hundred years of history, especially the enormous changes that have taken place in Chinese society over the last thirty years.

They constitute an era, and have also been swallowed by this era. A rough-shod time, but also a tender one. And as long as this tenderness exists, so does my hometown.

PROLOGUE

O NCE UPON A TIME, EVERYTHING you needed in life could be found at the front and back of your house. Back then, life was straightforward, fresh, and warm as the palm of your hand. People treated each other with compassion and care.

At Gaogang in Jiangsu, the Yangtze River makes a large bend. A smaller river branches off here, extending eastward. Along it stands a line of ancient ginkgo trees. Follow these another twenty-odd kilometers east, and youll reach Shen Village, where even more ginkgos grow. People call it the village of ginkgo trees.

Six hundred years ago, a man named Shen Liangsan came to this place from Changmen in Jiangsu. He fell in love with this low-lying, sandy piece of land and decided to settle here. In 1970, the seventeenth generation of his lineage was bornincluding me. Shen Village was now a large settlement with tens of thousands of people. No one could have expected that I and people my age were destined to watch our village decline and fade away.

In 2001, after more than a decade away from home, I returned to Shen Village, and saw, for the first time, a deserted house, its doors locked tight. That was the paper craftsmans home. His grave was at the back of the house, in a courtyard whose gate was fastened with a rusty lock. Weeds had sprung up among the green tiles of the roof. Since that day, every few years, Id notice yet another house had been abandoned and was falling into ruin.

After so many years away, I was more familiar with places abroad than with my own hometown, but still felt a sudden jolt of bone-deep sorrow. The people I knew well were withering away, one by one. Soon, this village would no longer exist. As a kid, Id run freely through the wilderness; now, half of it had been built over with factories. When the steel and cement of the city reaches Shen Village, with its six hundred years of history, it may well be reduced to nothing more than a mirage.