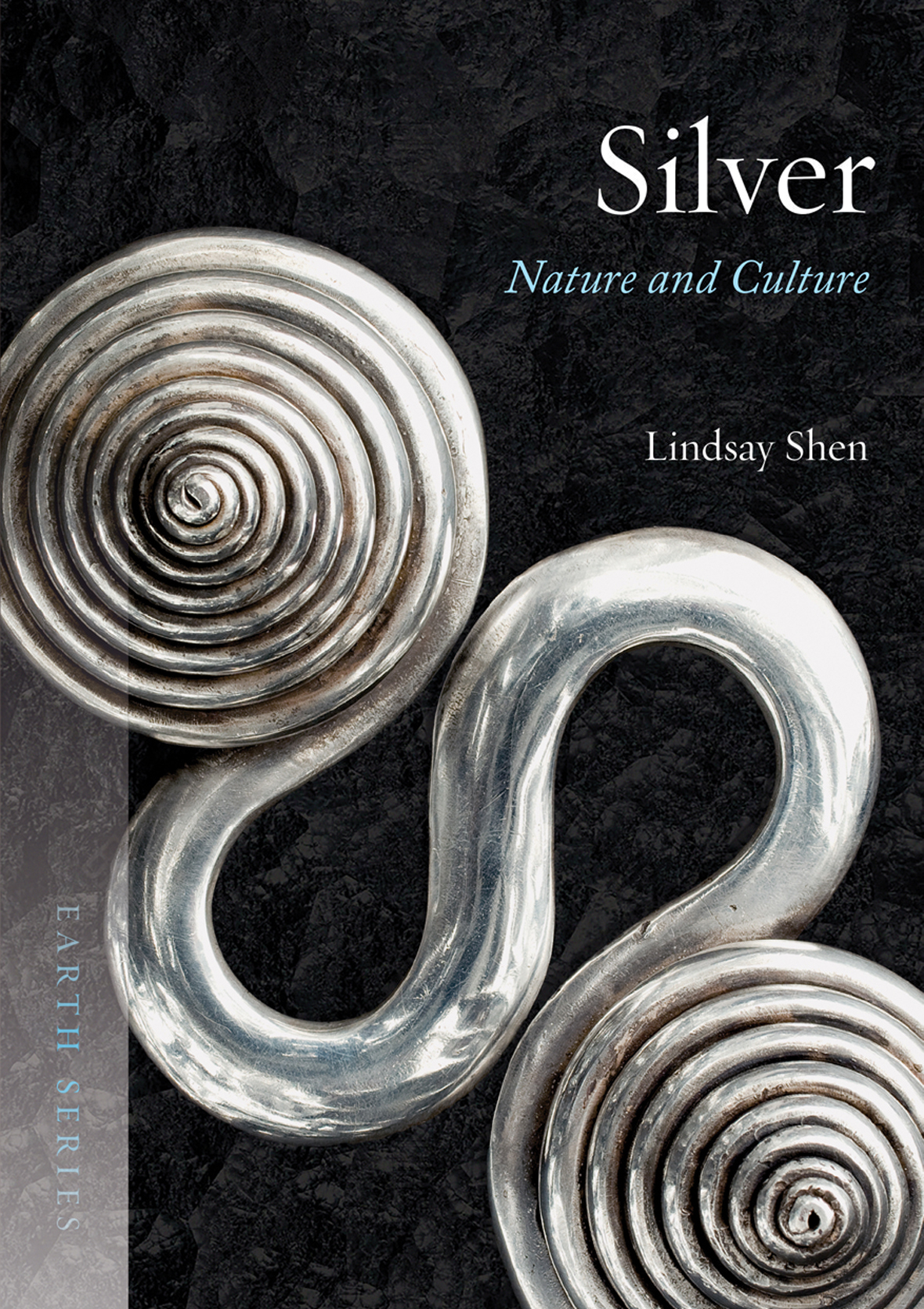

SILVER

The Earth series traces the historical significance and cultural history of natural phenomena. Written by experts who are passionate about their subject, titles in the series bring together science, art, literature, mythology, religion and popular culture, exploring and explaining the planet we inhabit in new and exciting ways.

Series editor: Daniel Allen

In the same series

Air Peter Adey

Cave Ralph Crane and Lisa Fletcher

Clouds Richard Hamblyn

Desert Roslynn D. Haynes

Earthquake Andrew Robinson

Fire Stephen J. Pyne

Flood John Withington

Gold Rebecca Zorach and Michael W. Phillips Jr

Islands Stephen A. Royle

Lightning Derek M. Elsom

Meteorite Maria Golia

Moon Edgar Williams

Mountain Veronica della Dora

Silver Lindsay Shen

South Pole Elizabeth Leane

Storm John Withington

Tsunami Richard Hamblyn

Volcano James Hamilton

Water Veronica Strang

Waterfall Brian J. Hudson

Silver

Lindsay Shen

REAKTION BOOKS

For my parents, Ewan and Audrey Macbeth, in gratitude

Published by Reaktion Books Ltd

Unit 32, Waterside

4448 Wharf Road

London N1 7UX, UK

www.reaktionbooks.co.uk

First published 2017

Copyright Lindsay Shen 2017

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers

Page references in the Photo Acknowledgements and

Index match the printed edition of this book.

Printed and bound in China by 1010 Printing International Ltd

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

eISBN: 9781780238012

CONTENTS

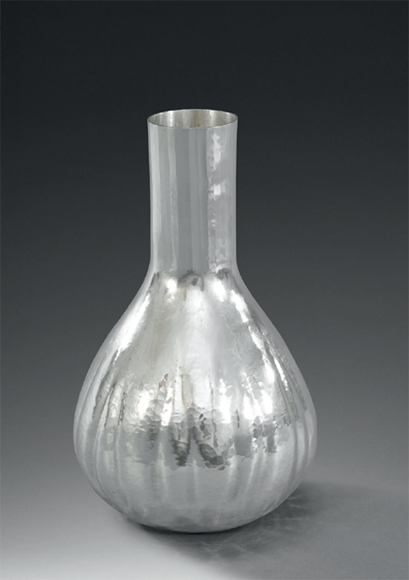

Charles Hall, water flacon, 2012, silver.

Preface: A Silver Object Lesson

Every cloud has a silver lining. And silver, like clouds, is seemingly everywhere. The aim of this book is to consider something that we have become so familiar with that we easily take it for granted. It is the stuff of our grandfathers coin collections and the hidden contents of our grandmothers cabinet drawers; it is in old photographs, our mobile phones and computer keyboards, our teeth, water, swimming pools, socks and bandages; it is what our New Age neighbours swallow as homeopathic medicine, and what investment gurus urge us to buy instead of equities; it is the banqueting dish offered at half a million pounds through the auction house, and the necklace on sale for 14.99 at the local accessories shop; it is in our language, our sayings and ideas (reports of silver bullets that will cure our problems surface in the media almost daily). Increasingly, with the development of nanotechnology, it is also in our bodies and those environments that have never been a natural home for silver. As an element, it is one of the building blocks of the earth, and like other building blocks such as oxygen, hydrogen, lead, sodium or iron, it simply exists.

But how? How does one silver object let us take a water flacon by the British silversmith Charles Hall come into being? At 24 cm (9.5 in.) high, the flacon is a modestly scaled object designed for holding and pouring water. The hallmark on its base provides us with a potted history of its making. The sponsors mark cfh is the initials of its creator. The letter n is the date mark, indicating that it was hallmarked in 2012. The leopards head is the symbol of the Goldsmiths Company Assay Office in London, where it was sent to authenticate the purity of the silver. The mark 999 is the millesimal fineness mark, which tells us it is 999 parts out of 1,000 pure silver. This is the standard we call fine silver, though most of the silver that we are familiar with is the lower purity sterling silver 925 meaning 92.5 per cent pure. The mark in the centre, depicting the Queens head in a diamond, is a special commemorative mark to celebrate Queen Elizabeth IIs Diamond Jubilee. It was handmade in Cornwall, but the silver did not come from a Cornish mine; there were silver (and tin, lead, zinc and copper) mines in Cornwall, but these have long since been worked out. Charles Hall sourced his silver in Italy, but his supplier drew on several sources. It did not come out of the ground ready to be worked. Unlike gold, little pure native silver exists in the earth. The material for this flacon had to be extensively refined before it reached Hall.

Hallmark on Charles Halls water flacon.

This book first asks the basic question, where does silver come from before it reaches the silversmiths workshop, medical laboratory or electronics factory? The silver for Halls flacon made a journey that can only be measured in geological time. Ore genesis (the forming of ores) takes millions of years. But, projecting beyond the formation of the earth, how did that process begin? Why are silver deposits found in certain places? What sort of geology allows silver to come into being? Nowadays mining exploration relies on geologists, geoscientists and engineers to determine the viability of mining in a promising location. But how were silver deposits discovered thousands of years ago? And what beliefs and mythologies grew up around the revelation of such a precious metal, the effort and expertise required to prise it from the earth and the almost mystical process of refining it?

An ancient idea held by many cultures is that of the miner collaborating with nature in birthing the precious metal. The reverse of this is the smith, through skill and ingenuity refashioning nature into art. Halls flacon, with its beautifully rounded shape that asks to be handled, was raised from a flat sheet of silver. Little wonder that the metalsmith has long been thought a magician. Raising is one of the oldest silver-working techniques we know about, and involves the smith hammering cold silver, which has a natural softness, over a form to create a dish or hollow vessel. A complex shape like the flacon, with its narrow neck, is more easily made from fine silver, which is especially soft. The greater the percentage of another material (usually copper), the harder the silver. It is not unusual for a smith to craft new tools for a project, such as the one Hall made to shape the specific curve of the vessel.

The flacons surface is textured with very visible hammer marks that change size and shape as they move up towards the rim. The hammering is functional in that it hardens the soft, pure metal, but it also creates shallow concavities that enhance the play of light over the surface of the earths most reflective metal. It is a surface that pools and flows and glistens like the water inside. The hammer marks were made by the hand of one particular silversmith, but belong to a craft stretching back millennia. The reverse of the question how is silver formed in nature? is how do humans form silver? How do silversmiths like Hall work with silvers natural properties, such as malleability and shine, to create objects of use, beauty, adornment and even magic? Silver has been cast into objects that even in their solid form seem fluid and living. It has been manipulated with such craft that over the millennia, smiths have conjured prancing horses, dancers, deities, flowers and landscapes from flat surfaces. It has been drawn on with engraving tools, drawn into wire, woven into sumptuous textiles and even crocheted.