Translated and with an Afterword by John K. Cox

PREFACE

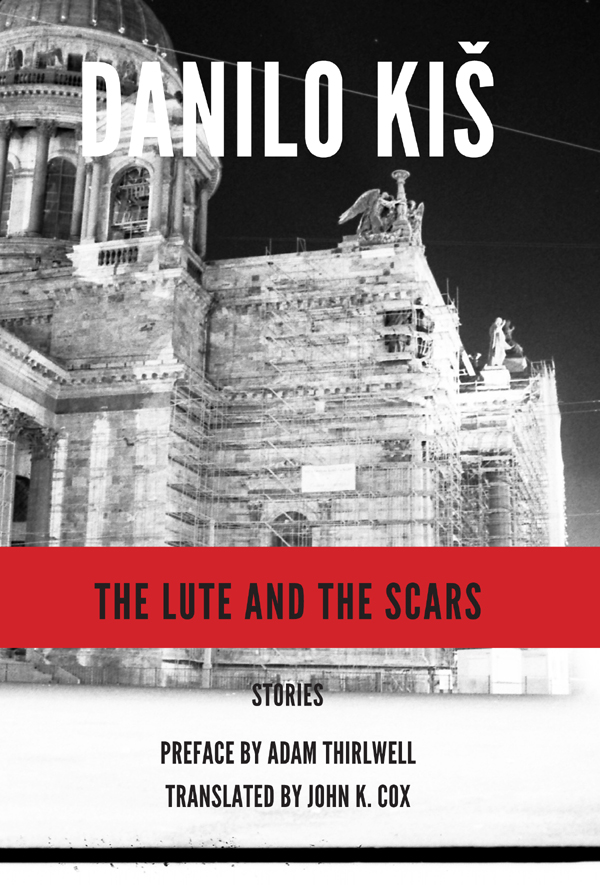

FOR DANILO KI

There are various ways of imagining a new era of world literature. My favorite is to remember the story of Danilo Ki.

His outside story is the devastated history of Central Europe. He was born in 1935. In 1944, his father, who was Jewish, was taken to Auschwitz, and did not return. In 1947, Ki was repatriated with his mother to Montenegro, where he studied art, then the violin, and finally entered the University of Belgrade in the Department of Comparative Literature. He would go on to teach Serbo-Croat to students in various French universities, and he eventually settled in Parisan emigrant in the self-imposed style of James Joyce. He died in Paris in 1989, when he was only fifty-four. But the inside story, the story of his art, is even more unique.

Can I put it in a highspeed sentence? His style was encyclopedia entries, definitions in historical dictionaries, legends told in footnotes, postscripts incorporating unsubstantiated rumor. His fictions very rarely looked like fictions. Instead, they adopted the look of annals or chronicles or pulp fictions. Because this, after all, is what happens to a life: if its remembered at all, its remembered in words. And this is the essence of the style called Danilo Ki: it is always an experiment with foreshortening.

And if his chronicler wanted to recount an exhaustive prehis-tory of this style, then traces could be found, sure enough, in Isaac Babel, and Dostoyevsky, as well as in Edgar Allan Poe. But the real precursor was Jorge Luis Borges. In Buenos Aires, in his fictions written in the first half of the twentieth century, Borges invented a way of writing stories by not, in fact, writing them at all. Instead, he described them in antiquarian summaries, as if these fictions were already written, already part of a minute literary history: in fake entries from catalogues or encyclopedias. In his essays and his interviews, Ki kept offering up new definitions of Borgess radical invention. It was, he said once, a

new way of using documents. It enabled him to compress his material to the maximum, which is, after all, the ideal of narrative art. I repeat: the document is the surest way to make a story seem both convincing and true, and what is literature for if not to convince us of the truth of what it tells, of the writers literary fantasies. Such is the direction Borgess investigations take, and they lead him to the pinnacle of narrative art and technique.

Or sometimes he put it like this, in the language of logic: The story... which emphasized detail and created its mythologemic field by means of induction, underwent a magic, revolutionary transformation in Borges: Borges introduced deduction... For this kink introduced by Borges into the normal order of a story was a liberation machine, an ejector seat. It allowed Ki to ignore so many of the old-fashioned problems, like character and psychologyall the otiose mechanics of verismo . I mean: you could make a Ki anthology of irritation at the previous deadend methods:

Example 1

What I cant stand is the serialized or feuilleton -type fiction of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries and its hidden omniscient author...

Example 2

... the omniscience of the narrator and the art of psychological portraiture, those most pernicious and persistent of literary conventions.

But the history of world literature isnt a history of repeats. The Borges system was a gorgeous thing, but Ki invented his own kink in that tradition too. For Borgess stories are inventions from the innocent half of the twentieth century. Whereas Ki came in the aftermath. The entropic centre of his electric fictions is the centurys twin death camps: the camps of the Nazi rgime, and the camps of the Soviet rgime. All history is crime, in Kis fiction. (No wonder he wrote a great, sympathetic essay on the fictions of the Marquis de Sade.) Borges had called one of his books A Universal History of Infamy , but his idea of infamy was so much more minor than anything Ki knew: it was barrio gangsters and pistolets. So that where Borgess stories were really always investigations of metaphysics, wrote Ki, he himself investigated the violent networks of commissars and kommandants . He used the document method to investigate history: mans soul having long since been given up to the Devil.

His impatience with the usual psychological novel, in other words, was part of a deeper investigation. Confronting imaginary characters with psychology is to my mind anachronistic... Well, sure! It had been taken over by what Ki called schizopsychology the mass and murderous neuroses.

Hiroshima is the focal point of that fantastic world, whose contours could first be discerned at about the time of the First World War, when the horror of secret societies began to come to life in the form of mass ritual sacrifices on the altar of ideology, the golden calf, religion... I say secret societies because I am speaking of the occult...

History is a history of violence. It always ends up as a garbage heap. And so, in response, literature has to itemise and restore the garbage. This was Kis wisdom. He once imagined a story that would be a description of a trash can (just as Calvinoanother student of the Borges systemwould try in his own late essay on garbage.) I believe that literature must correct History, wrote Ki. Its job, in other words, was the restoration of corrupted texts.

In Kis early fiction ( Garden, Ashes , or Early Sorrows ) he invented his first method of restorationa kind of luminous autobiography, in the magical imploded first-person voice of a child. This voice is only foreground, an encrusted surface of detail that wont givebut it gives everywhereonto the catastrophic history underneath. It is total indirection.

And this indirection is one of Kis most savage innovations. You dont know what showing means, I think, until youve read his stories. This kind of indirection might have been the professed nineteenth-century ideal, a prim dislike of telling, but Kis indirection is more wayout and final than, say, the grand fictions of Henry James. It was the only way he could find to encompass his vast material. For to name is to diminish. Only by concealing a theme can you approach its total description. And so the reader is slowed into stillness by the density of detail in his prosealways about to transform itself into a list. I mean: you could make another anthology out of Kis love of the list:

Example 1

This non-alphabetic enumeration, the onomasticon, is the system perhaps best suited to reflect the chaotic crisscross of the prose of the world , the magma that verbal mechanics merely seems to set in order...

Example 2

Reading the Bible, Homer, or Rabelais, I keep finding devices engendered by the disparity and incongruity of objects in chance encounter.

Which is another way of saying that the detail in Ki is part of his new deductive method, its based on his deep principle of collagenot the dead inductive methods of previous fiction. And this is why, in the 70s, when Borges was translated into SerboCroat for the first time, it was possible for Ki to develop a new technique out of the old one. And so, in his great books from the 1970s, Hourglass and A Tomb for Boris Davidovich , he moved from the first person to the third person. In Hourglass , this created the intricacy of its form: where alternating manuscripts are finally endstopped by a single document: a letter dated April 5, 1942. In A Tomb for Boris Davidovich , this created the delicate juxtapositions of his stories about the Stalinist machine: their principle of thematic germination. His technique of the legend became complicated by the technique of the document.