Contents

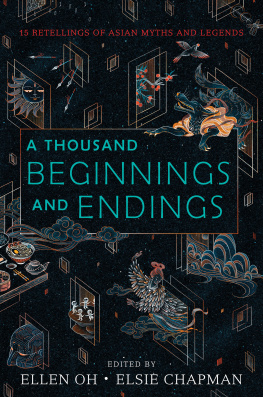

Dear Readers,

For one of us, it was the first book a librarian gave to her when she finally summoned up the courage to ask for a book recommendationThe Pink Fairy Book, by Andrew Lang. For the other, it was the one book she ever stole from her elementary school librarya book on mythology. (Not that it was okay to steal the book, but she will finally admit to it now, more than thirty years later, with the school shut down for good, and said thief living on the other side of the world from her hometown.)

We both went on to devour other mythologies: Greek and Norse, from Ares to Danae to Thor to Odin. We fell in love with all those myths about powerful gods being vulnerable, about humans becoming heroes. Such stories taught us about mythology, about the beauty of folktales and legends, and about how stories of gods and goddesses are also stories about the human heart.

But we never found similar compilations that were distinctly Asian. And so many times when we found Asian stories, they were ones retold by non-Asian writers that never felt quite right. They were always missing something. The stories felt superficial at best and at worst, quite hurtful. We longed for nuance and subtlety and layers, the embedded truths about culture thatmore often than notcan only come from within.

Thats why this anthology is so important to us. Here, diasporic Asians reimagine their favorite Asian myths and legends from their own viewpoints. We would have been overjoyed to have found this anthology, filled with characters with skin and hair and names more like ours, in our beloved libraries. Its the book that was missing in our lives for far too long.

Beautiful, heartbreaking, moving, and brilliantthere are not enough words to describe how much we love all of these stories. We hope that you will love them, too. To be able to bring this book to you, written by these amazing Asian authors, is a dream come true.

Elsie Chapman

Ellen Oh

D o not trust the fruit of Maria Makiling.

If you find your pockets full of thorny fruit, throw it out the window. Do not taste it. Do not stroke the rind and wonder at the impossible pink of its color... not meat pink or tongue pink, but that delicate rose of dawn pushing herself from the arms of night. It is not a color of this world.

Fill your pockets with salt. Turn your shirt inside out. Tell Maria you have taken nothing.

But when you walk away, say a prayer.

For it is not her fault.

The Mountain couldnt help but stare.

She had been staring since the moon was nothing but a knob of unripe fruit, and she had been leaning out over her palace since the sky was still the raw and wounded red of a newborn.

Mortals were not beautiful in the sense that their features were pleasing, although some of them had pleasing features, of course. But in truth, they were beautiful because you could only glimpse them. They were beautiful for their fragility, disappearing as fast as a bloom of ice beneath sunlight. And made more beautiful by the fact that they were always changing.

Dayang, said her father, peering down from his clouds. Be careful not to lean out so far that your heart falls out.

The Mountain merely laughed.

Her heart was safe.

It was an ill-fated thing to claim that a heart is safe. Hearts are rebellious. The moment they feel trapped, they will strain against their bindings.

And it was so with the Mountain.

Few visited her, for few could climb the sides of the Mountain. In this way, the Mountain diwata discovered loneliness. It was the feeling of negative space, the sudden cold of a column of sunlight moving slowly elsewhere. The diwata wondered what it would be like to be held by the same set of arms each day and night. The Mountain shed lovers like seasons. It was the diwatas way, just as fruit could not help but fall, and rain could not help but slide.

One day, the diwata went near the bottom of her slope and bathed in a small pool there. When she finished, she let her black hair dry on a sun-warmed rock. Her eyes closed.

She waved her hands lazily, sleepily. Beneath her palms, a cluster of anemones unfurled from the ground and nuzzled her fingers. A face rose to mind: a human boy with sloe eyes who had wandered up the Mountain a few days past. He had not seen her, which had not surprised her. But what had surprised her was the flare of disappointment in her heart. She wanted to be seen.

A quiet snap broke her thoughts.

A different silence chased the stillness. It was not the silence of emptiness, but intention. It felt like a living thing.

Someone had meant to stop.

The Mountain jolted upright.

There, standing in the clearing of the woods, was a young mortal man. He wore a beautiful hunting cloak and held a knife, but when he saw her, he dropped it. He sank to his knees, flinging out his arms.

Goddess, I beg your forgiveness, said the young man.

The Mountain held back a snort. It was not kind to laugh in the face of faith. Yet she was still young, too, and had not learned how to mask her features. Around her, the wind crinkled the leaves.

The young man looked up from his prostration.

I am no goddess, said the Mountain.

His eyebrows curved into a question. Are you not the spirit of the Mountain?

I am.

But she thought of her mother, her sistersthe ones who spent their time painting stars onto the sky, swelling rivers, and dreaming of new beings. Not like her, whose duty was to tend and not create. Not that the Mountain minded. She got to be close to something that was just a distant dream to the others. She got to be near humans.

The man stood. The Mountain stared. His eyes were not yet crimped by too much sun. His hair was raven lustrous and his muscles lean and sleek. Her heart, though still firmly behind her bones, leaned out curiously.

Then forgive my presumption, he said. I couldnt help but think that the most beautiful woman I had ever seen would naturally be a goddess.

She pushed herself off the rock and walked toward him. His eyes widened, wonder tilting his brows and parting his lips. A thrill ran through the Mountain. She laced frost in her hair like a bejeweled net to gather the black strands and expose the steep drop of her neck. Her dress shone sheer and iridescent, crafted of a thousand beetle wings and shells polished to the point of translucence. When she touched him, he shuddered. She wanted to put her lips at his necks pulse point, to sip lightly at all the things that made him human.

I would have you, she said simply.

The mans eyes widened. And the Mountain, though she could neither bend nor break, felt her landscape ripple beneath that gaze. He was the first human to see her. It was one thing to crouch unseen and stay separate. It was quite another to stand beheld.

She reached for him, and he reached back.

The Mountain had loved and been loved by many. But none had been human.

It was different. His blood ran hot beneath his skin. There was urgency here... and the Mountain wondered distractedly whether it might scorch her.

Immortals have no urgency. There was never any rush. All lovemaking was slow as poured honey.

This was not.

And the Mountain rather liked it.

What is your name? she asked, when they lay still on a bed of anemones.

Bulan, he said.

Language was not yet pleated into symbols. She could not trace his name upon his chest. Instead, she sounded out the name against his wrist, beneath his ear, upon his neck.