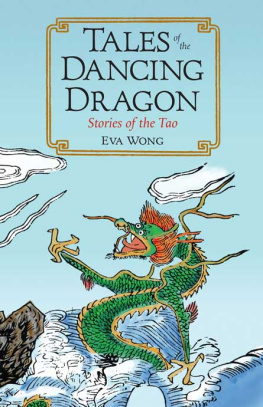

TALES

FROM

THE TAO

Contents

Introduction

Stories have always formed a large part of Taoist teaching. The books of Chuang Tzu and Lieh Tzu are full of interesting, entertaining, illuminating, puzzling and often downright funny stories. They are primarily teaching stories, using narrative and character to share some aspect of Taoist thought or practice. The only drawback is that they are so short, often only a paragraph or two. This work is an attempt to flesh out these stories, giving them more room to breathe, to evolve, and to give the characters of the stories more time to develop into fully realized people.

These tales introduce traditional Taoist principles and ideas about many of the most basic human experiences birth, death, loss, gain, simple dignity in the face of challenge, how to judge the character of a person, when to move forward, when to retreat, how to deal with fame and how to surrender to the most fundamental experience of the Tao itself.

Most of the stories are from the classical writings of Chuang Tzu and Lieh Tzu but then again some are entirely original, being inspired by traditional Taoist tales, such as how the famous Tao Te Ching was written. The stories are from the early days of Taoist thought, the golden age of Lao Tzu, author of the most famous Taoist text, the Tao Te Ching (the classic text of the Way and its virtue); Chuang Tzu, author of at least part of the book that bears his name; and Lieh Tzu, whose work also bears his name.

A word on Taoism here. In its early days Taoism was more of a philosophy or way of life than a religion. In later years, various strands of Taoist religion were formed, two of which are still active today the Tianshi Dao or the Way of Heavenly Masters and the Quanzhen Dao or The Way of Complete Perfection. Today many people use the terms Daojio and Daojia to differentiate between the religious school of Taoism and the philosophical teachings of Lao Tzu and Chuang Tzu. Interestingly, when Buddhism came into China in the 5th century, it became mixed up with the native Taoist traditions and became quite a unique form of Buddhism, called Chan, which later on travelled to Japan where it was taken up by the samurai class, who laid over it a layer of their own bushido philosophy and named it Zen.

In these texts we are introduced to ways of living our lives in harmony with the forces of nature and the world as well as the inner forces of our own often confused and ignorant self-nature. Much emphasis is placed on being true to our own authentic nature, which Chuang Tzu calls the Authentic or Real Person. Over and over we are shown that to be authentic or enlightened means to be at once a part of the world of change and yet also to be able to operate outside space and time (as described by contemporary scientists who are working with quantum theory).

We are taught that to be truly free we must be able to work with change rather than against it we must be able to dance gracefully with the ever-unfolding panorama of change that constitutes life. We are also taught that to remain simple, even if it appears to the outside world that we are simpletons, is the best way to align ourselves with the ever-unfolding Way. In addition we must be humble, flexible and detached from outward form.

Life in the modern world is full of stress and anxiety; appearing to speed up at an ever-increasing rate such that many things of lasting value have no currency in this age of internet dating and reality television programming. Yet it is still possible to gain both understanding and knowledge from these tales of the Tao, written thousands of years ago.

My intention with these stories is to stimulate thought, insight and even emotion as regards the lessons of this ancient yet evolving body of teachings. The ancient stories of Taoism are as relevant today as they were in the Han dynasty and before. The insights and ideas that they present to us can be of great assistance in troubled times.

So sit back, relax and with your breath rising from your heels, spend some time with these thought-provoking, heart-opening, funny-bonetickling tales.

SOLALA TOWLER

The Tales

TALE 1

To Be or Not to Be, A Butterfly

The butterfly flitted on its way, unmindful of the gentle breeze that ruffled its wings. It flew here and there, content in its own way to wander without a goal, without any needs except to be part of the breeze that blew past its wings as it flew along, unhurried, unfurled and even.

This little butterflys life had been brief. From caterpillar to chrysalis inside its quiet and heavy cocoon, it had stayed for what seemed eons of time quiet, patient, waiting for the moment when it could break out of its prison, unfurl its wings and fly straight up into the air.

Now it did just so, flitting around in circles, occasionally meeting up with another butterfly, always mindful of predators or a strong and sudden gust of wind that could tear at its thin, translucent wings and send it hurtling down to earth.

Now and again the butterfly seemed to have glimpses of another life, another form. It seemed to be a much heavier and more ponderous life, this other one. But usually the butterfly ignored these unsettling inner sightings and just did what butterflies do, without thought, without motive, without any other goal than just to be what it was, a butterfly flying free.

And as it did so the day lengthened into night and the butterfly headed back to the tree where it slept through the long period of darkness. It flew gently toward it and then suddenly stopped.

The man lay in his bed, bewildered, bemused, lost in thought. It had seemed so real to him, this gentle butterfly life. He lay in the early morning light, listening to the sounds of the village as it slowly came to wake all about him. He heard the creaking of doors as people made their way to the outhouses. He heard the sudden squall of an infant, the bark of a dog, the clomp of an ox as it trudged out to the fields, led by its sleepy master. He heard the sounds of fires being built, the tea kettles and the rice pots being readied for breakfast.

He lay there a long time, without rising, without moving, other than the slow and deep rising and falling of his belly as he breathed his way into the day. His dream, if that is what it was, had been so vivid, so real. He had actually experienced himself as that butterfly had felt the breeze on his wings, felt himself carried through the air as light as a seed, had thought only butterfly thoughts. Yet now, here he was, back in his human body, back in the world of cause and effect. But which was truly real and which was the dream himself as a butterfly, or himself as a man, waiting here for his students to come and drag him out into the light of day with their incessant questions and demands?

How did he know that what he was experiencing now was not the dream? That he really was that butterfly, living its simple butterfly life, unattached and a part of the great natural world of Tao. He smiled in the darkness then. Truly, it did not matter if he was a man who had dreamed he was a butterfly or a butterfly who was now dreaming he was a man. He knew what he knew and he knew what he didnt know. That was what sustained him through the long days and nights of his human life. What he knew or experienced in his butterfly life was also there, just outside the periphery of his vision.

Next page