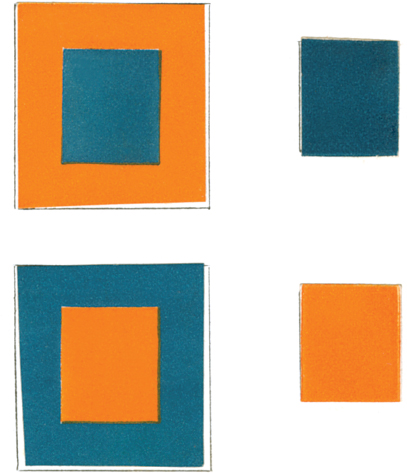

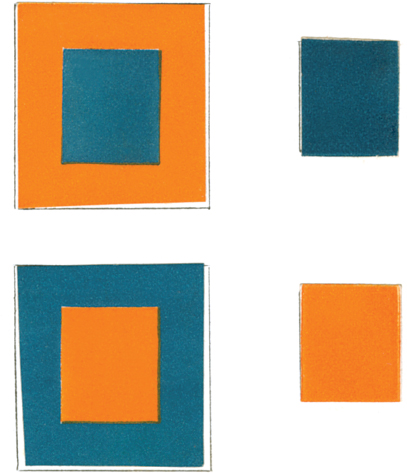

An example showing the reciprocal influence of blue and orange (see ).

Y ELLOW G REEN

G REEN WITH R ED

B LUE G REEN

B ROWN M ADDER AND O RANGE

B ROWN M ADDER AND G REEN

Examples showing how the perception of color can change when two colors act on each other (see ).

The Practice of Art

A Classic Victorian Treatise

The Practice of Art

A Classic Victorian Treatise

J. D. Harding

Illustrations drawn and engraved by the author

DOVER PUBLICATIONS, INC.

Mineola, New York

Bibliographical Note

This Dover edition, first published in 2016, is an unabridged republication of the work originally published by Chapman and Hall, London, in 1845, under the title The Principles and Practice of Art. The original color studies in chapter VII have been reproduced here in full color on the inside covers; they also appear in black and white in their original positions in the book.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Harding, James Duffield, 17981863, author.

Title: The practice of art : a classic Victorian treatise / J.D. Harding.

Other titles: Principles and practice of art

Description: Mineola, New York : Dover Publications, 2016. | Series: Dover fine art, history of art

Identifiers: LCCN 2016033252| ISBN 9780486811284 (paperback) | ISBN 048681128X

Subjects: LCSH: Art. | BISAC: ART / Techniques / General. | ART / Techniques/ Drawing. | ART / Techniques / Printmaking.

Classification: LCC N7425 .H3 2016 | DDC 700dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016033252

Manufactured in the United States by LSC Communications

81128X01 2016

www.doverpublications.com

PREFACE.

I N my Treatise on Elementary Art, which I intended as preparatory to the present work, I confined myself to the study of objects individually, and to their imitation by the simplest instruments of Art,the lead pencil or chalk; and I endeavoured to direct the mind of the student to those principles and laws of Nature, which it is so necessary constantly to observe and supply. Whilst giving this instruction, which may be considered as the Alphabet of Art, I urged on the student the importance and superiority of that kind of imitation which is mental rather than mechanical,which endeavours to express what the artist feels when viewing his subject as a whole, rather than to minutely copy that which he can only see when intently looking at a single part.

In the present work I have pursued the same course, from a conviction of its being at once the most simple, comprehensible, and useful; and in explaining the more recondite principles and more complicated practice of Art, I have constantly endeavoured to express my meaning in plain language, avoiding the use of technical terms, which, though current amongst artists, yet have even with them no definite value, but pass for what they are worth according to individual opinion.

In treating now of Imitation, with respect to the employment of composition, light-and-shade and colour, I have offered nothing which depends for its authority on myself, or on the practice of any school at any period. My object has been to explain truths which are ever-existent in Nature, to derive from them the principles of Art, and to show how those principles are to be carried into practice.

By the word practice, I do not mean the mere manipulation of the brushes and colours ; this is better learned in one day by seeing a painter at work, and receiving his viv voce instructions, than it could be taught in any book. All the methods of using the materials are simple enough when witnessed, but appear extremely complicated in a written description.

In the Elementary Treatise my object was to teach the Rudiments of Art : to explain its more recondite principles, to exemplify them graphically, and to instruct the student in their application, is the chief object of the present work. Although the selection of subjects depends on the predilections of the painter, yet the appropriate arrangement of the objects, the light-and-shade, and colour in a picture, may be suggested, if not strictly determined, by principles deduced from the study of Nature.

Throughout I have endeavoured to show, that, though pictorial Art is founded on imitation, yet to imitate mechanically by exact representation all the visible properties of objects is not only impossible, but, if it were possible, would be useless.

I have also endeavoured to show how the judgment and feelings, both separately and in combination, operate in the practice of Art. If I have succeeded in explaining myself, it will be apparent that no new faculty or sense is required to comprehend the principles upon which excellence and beauty in Art depend.

The remarks I have made on the works of some of the Old Masters may appear strange to those who have never heard their names mentioned but in connexion with the most extravagant terms of praise. I am not, however, one of those who think that the old masters, Dutch or Italian, are the exclusively excellent, nor that they have exhausted all that is beautiful and interesting both in Nature and Art ; neither do I regret, while honouring the talents of the really great among them, that we have no modern painters to rival them in the departments in which they have deservedly won distinction, and, from the right of pre-occupancy, made to a certain extent their own. Of their works there is no deficiency; and for the purposes of study we have more than enough, even if great painters could only be formed by studying and copying the works of their predecessors. But, in order to attain a high degree of excellence, something more than such a study is required. Nature puts in her claim to our attention : she is the great source of knowledge and feeling, and whoever neglects to seek inspiration at this source will never become a great artist.

Changes in manners and customs, as well as in the tastes, feelings, and opinions of society, have in more recent times given a new impulse to talent, and stimulated its exercise in other directions, and on other subjects, than those generally followed and chosen by the old masters.

Should it be objected, that the present work treats too much on Landscape, I would reply, that general principles are applicable in every department of Art; and that, if their application is not here so much exhibited in Historical Subjects as in Landscape, it is because I am not both an historical and landscape painter.

J. D. H.

L ONDON , 4, G ORDON S QUARE ,

3rd June, 1845.

ERRATA.

, line 9 from the top, for bad, read common-place.

, line 24 from the top for Example 2, read Example 3.

, in the Diagram, for black, read grey.

AUTHORS NOTE.

T HE Note at the foot of was written when I intended to give all the Illustrations in Lithotint ; but I afterwards adopted Engraving, as it more fully exemplifies my meaning.

Next page