Table of Contents

For Amir and Sana

Contents

Cinema in India, as elsewhere too, is one of the most crucial parameters to gauge the changing shifts in society at political, sociocultural and even economic levels. A film is not created in a vacuum. It has its own distinct space, roots and character.

At the outset, I wish to declare that I believe in looking at Hindustani cinema based on Indian parameters. Cinema in India is a genre in itself. One should not look at and analyse it on parameters made commonplace by the West. The Western definitions of the words musical and melodrama are not applicable to Indian cinema. In the same way, the idea of a multi-starrer or a devotional film might sound alien in world cinema.

When a film is made for Indian audiences, it needs to be evaluated and understood from their perspective. The perspective of looking at a film should depend on the origins and circumstances of its viewers. I am not sure if

I subscribe to Paul Willemens Cinephilia, the theory which suffers from considerable neglect in film theory. Instead I consciously attempt to look at Indian films through a certain innate Indian-ness.

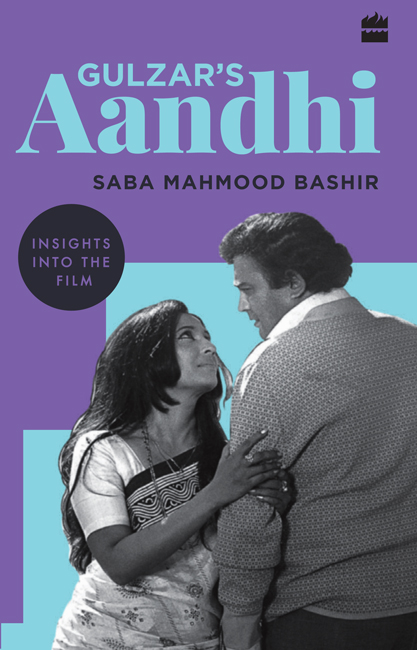

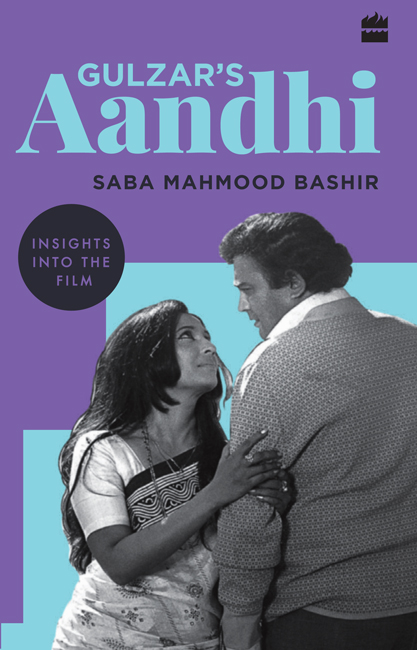

That said, I have translated Gulzars Aandhi on self-established paradigms. An attempt has been made to look at the structure of the film, by being cognizant of the fact that the story is set against the turbulent political backdrop of elections and politicking between various political parties and its leaders. The analysis of the cinematic text led to the exploration of the visual, narrative and self-reflexive elements of the film. This book further explores the very essence of the film: the love story between a hotel manager (JK), and his ambitious wife (Aarti), who aspires to be a minister one day. A close textual analysis has been adopted to view the film and delve into its layers.

Sumita S. Chakravarty points out that the Hindi-Urdu word for a film screen is purdah, or curtain that which hides rather than reveals. Popular Indian conception of the cinema, therefore, associates film with the invisible rather than the visible. Building on this premise, one can unravel the ambiguity apparent in a film.

I am also wary of the generic classification of films into art cinema and popular cinema. These parameters have been created by different theorists and critics. However, most films cannot fall in such distinct categories. What are the base parameters that put the films in tight compartments? Would a film be art if it depicted the harsh reality of a country? If it featured a romance-driven plot with song and dance sequences, would it be commercial cinema? It doesnt stop there. There are various categories in commercial cinema as well mythological, historical, action, romantic-comedy, etc. Also, there are Indian commercial films which do well overseas, and has an international presence. What about films like Pyaasa (1957), Mother India ( 1957) and Mughal-e-Azam (1960) to name only a few where the so-called boundaries between art and commercial cinema clearly seem to have blurred and merged? Aandhi is one such film. It was a commercial success featuring a strong, memorable love story, which was also a tongue-in-cheek comment on the then political scenario of the country.

This book is divided into five chapters. It begins by looking at its filmmaker, Gulzar, and how Aandhi is a directors film, all the way. The first chapter also focusses on why he chose this story, originally written by Kamleshwar.

The second chapter focusses on the controversy surrounding the film. Critics pointed out the resemblance of the films female protagonist, Suchitra Sen, to the then prime minister of India, Indira Gandhi. This eventually led to a ban on the screening of the film. It also expands on how Aandhi goes beyond a mere romantic film and becomes not only a statement of the then political situation in India, but also alludes to the undercurrents between the common man and his ideas about the political leadership of the country.

The next chapter is on the films stellar cast comprising not only the actors who played the two protagonists but also those in supporting roles, all well etched out.

Poetry plays a crucial role in the screenplay; so the fourth chapter is on the songs, which played a major part in making the film a commercial success. Three of the songs in the film showcase three different stages in the life of the couple and their complex relationship. Another important song, a qawwali, is a strong political commentary on how a common man views politicians.

The last chapter in the book looks at the language used in the film. The dialogues have both wit and humour both in scenes involving the personal lives of the couple and those highlighting the political drama.

The interview of the filmmaker has been referenced throughout the book. It has also been provided as an appendix, as it gives a strong insight into the many things that went into the making of Aandhi . The lyrics of the songs form the other appendix.

Toot ki skaakh pe baitha koi

bunta hai resham ke taage

lamha lamha khol raha hai

patta patta been raha hai

ek-ek saans baja kar sunta hai saudayee

ek-ek saans ko kholke apne tan pe liptata jaata hai

apni hee saanson ka qaidi

resham ka shaayar ek din

apne hee tagon mein ghutkar mar jayega

(Sitting on a mulberry branch

Weaves some silk threads

Unwrapping each moment

Picking each leaf

Listening to every breath

Drapes self with each breath

Prisoner of his own breath

This poet of silk

Will die smothered in his own threads)

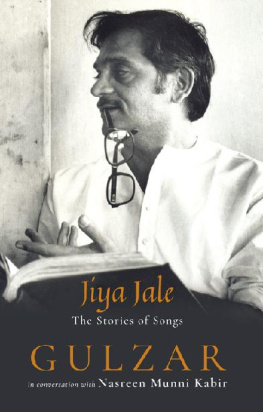

Gulzar. The name says it all. The poet, who is also a lyricist, filmmaker and dialogue writer, has more layers to his persona that one can delve into. Author of several anthologies of poems ( Kuch Aur Nazmein , Pukhraj , Raat Pashmine Ki , Triveni , Yaar Julahe and Pandra Paanch Pachchatar ) and writer of short stories ( Raavi Paar, Aththaniyan ), he has not only written extensively for children ( Bosky ka Panchantantra 15 , Karadi Tales , Potli Baba ki , Mangoo aur Mangli , Bosky ke Taal Pataal , Hindi for Heart and many more), but has also been translating from Bengali, Marathi and English.

Gulzars mass appeal, however, is through cinema. Writing for Hindustani cinema for more than half a century, Gulzar started his career with assisting filmmaker Bimal Roy for Kabuliwala (1961). Based on a short story of the same name by Rabindranath Tagore, it was for this film that he also wrote the song Ganga aaye kahan se (Ganga, where do you come from?). However, the song that got released first was from the film Bandini (1962); based on Vaishnavite poetry, the lyrics went: Mora gora ang lei le, mohe shyam rang dei de (Take away my fair colour, give me the colour of Krishna). Gulzar calls this song his entry pass into cinema. Although he was noticed with his very first song, it was with Humne dekhi hai in aankhon ki mehakti khushboo (I have seen the fragrance in these eyes) from Khamoshi (1969) that he truly arrived. On the one hand he was applauded for the use of his unusual and juxtaposed imagery which later became his signature style and on the other, he was also criticized by traditional poets for this approach. Whatever the argument may have been, it was this song that brought Gulzar to the forefront of poetry writing in cinema.