Jiya Jale

INTRODUCTION

The Journey of Songs

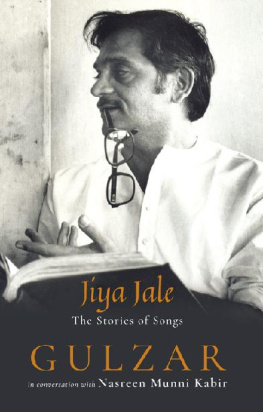

The idea for this book dates back to 2016, when Mani Ratnam asked me to subtitle the restored print of his film Dil Se (1998). Subtitling dialogue can be a challenge and translating songs particularly so. There can be an infinite number of interpretations and translations of any text, but ultimately there is only one original. So when I started working on the songs from Dil Se , I thought it would be hugely instructive if Gulzar saab, who had written the lyrics, could guide me in conveying the essence of his words.

Gracious as ever, Gulzar saab agreed and asked me to come over the next morning to his Pali Hill home in Bandra, Mumbai. Knowing he is fabulously punctual, I made it a point to arrive on time. He greeted me warmly, asked a staff member to bring me a coffee (Mummy-vali coffeethis is milk coffee, no sugarthe one they make for Raakhiji) and we settled down to work in his study. We began with the iconic Dil Se song, Chal chhaiyyan chhaiyyan. Though I had seen several English translations on the Net of this popular number, I found many very mediocre, while others seemed unashamedly comic. The best way to avoid a similar fate, I believed, was to discuss the song translations with Gulzar saab himself.

The result of this session made its way into the subtitles of the restored print of the film, and was later published in the Mumbai edition of The Hindu in January, 2017. The article featured the original song in romanized script accompanied by the English translation. Reading the article in The Hindu , it seemed such an interesting way of understanding song-writing from the point of view of the lyricist himself. Imagine how amazing it would be today to read Sahir Ludhianvi or Shailendra speak about their choice of words and images. Here was an unmissable opportunity of recording a leading lyricist of our time, Gulzar saab, and gaining an insight into his approach to song-writing.

To discuss the possibility of such a book, I went back to see Gulzar saab and fortunately he liked the idea. Straightaway he suggested contacting Ravi Singh at Speaking Tiger to ask whether hed like to publish Jiya Jale . Gulzar saab added: Ravi is a very soft-spoken and genteel manthe perfect publisher. He talks like a poet. Let me call him. Everything fell neatly into place, and over the next year, this book took shape.

Jiya Jale is, in fact, my second collaboration with Gulzar saab. The first being a book of conversations called In the Company of a Poet , published in 2012, which looked at the broader sweep of his life and work. The aim here is to focus on the backstories of how some of his most memorable songs came to be written, to discuss the work of the composers and singers with whom Gulzar saab collaborated and to translate a selection of his songs into English.

In my translations, I have avoided trying to make the lines rhyme in English, as this invariably leads to introducing new imagery into the lyrics. The translationswhich have been done with the expert advice of Gulzar saab himselfare not meant to be performed, as they were not written on the metre of a tune. Rather, the idea is to help us understand the many layers beneath the lyrics. This should allow a non-Hindi or non-Urdu fan of Gulzar saabs work to get a sense of the word meanings and the spirit of the songs.

A man of many skills, Gulzar saab is a poet, film director, screenplay writer, as well as the author and translator of countless poems and books. Many of his songs have become part of the cultural fabric of Indian life; songs like Kajra re are regularly played at weddings and Humko mann ki shakti dena is still sung at school assemblies. His songs evoke all kinds of emotionssome political or philosophical, while others are deeply romantic. In his film songs, he combines the skills of a poet with an understanding of the demands of the narrative. Often conversational in tone, many of his songs replace a melodramatic scene or dialogue with suble suggestion. Take Mera kuchh saamaan... from Ijaazat (1987), in which the end of a relationship is described in a heartfelt yet surprisingly matter-of-fact way. Instead of building up the drama the song words suggest a storm of inner emotions.

Many writers struggle to achieve a recognizable voice, but from his first song, Mora gora ang lai le ( Bandini , 1963), Gulzar saabs innovative style stood out. That said, some of his songs have come in for criticism over his use of metaphors. For example, critics asked how he could speak of the fragrance of the eyes in Humne dekhi hai un aankhon ki mehekti khushboo ( Khamoshi , 1970). Yet it is these very unusual juxtapositions of poetic images that set him apart. We can see, when analyzing his work, that his use of imagery is not intended to be literal, but rather evocative.

Gulzar saab and I began the conversations for this book in early 2017 and they continued in stop-and-start fashion till April 2018 (I live most of the year in London, and Gulzar saab is, of course, in Mumbai). Each of our fifteen or more sessions lasted for about two and half hours and were recorded on a digital recorder, then transcribed.

Gulzar saabs sense of discipline is hugely impressive; he is at his desk, writing or reading, six days a week from 10.30 to 1.30, with an hour for lunch, before going back to his study till 6 pm. He has several books on the go at any one time and is simultaneously writing a number of songs for a number of films. Many visitors drop in and his phone rings constantly, yet his attention remained undivided when it came to our work together. He does not rest until he finds the right word and the right tone for his expression.

When the manuscript was ready, Gulzar saab and I went over it several times to get the flow right and to make sure the book accurately captured the essence of our talks.

Today there is a welcome increase in the number of books on the history of film music. This book aims to provide a novel understanding of the Indian film song. In addition, it is a behind-the-scenes record of the process of song translation from the point of view of a master songwriter who believes: Translation is capturing the feeling that words evokethats more important to me than the meaning of the words.

NASREEN MUNNI KABIR

London

October 2018

Jiya Jale

Gulzar with Asha Bhosle and RD Burman.

Gulzar (G): Let us start with Jiya Jale.

That was the first song Lataji recorded with AR Rahman. Years before working on Dil Se , Rahman had grown up knowing the legend of Lata Mangeshkar, and the fact that he had not recorded a single song with her prior to Jiya Jale intrigued me.

One of Rahmans ways of working is thinking of a voice that would best suit his compositionand whether they are known or not, he will choose a singer whose voice matches his imagination. Hes a man who is honest to his vision and for him the texture of a voice must match the tune. The singer must also be someone who is happy to go to Chennai, if they live elsewhere, and record in Rahmans studio, even if it is late into the night.

So, like a film director who has the face of an actor in his minds eye while reading the script and understanding the nuances of a character, the face of a voice comes to Rahman. And it seemed that Latajis face had not appeared to him before Dil Se . We must remember that by the mid-1990s, Rahman was the leading film composer in India.