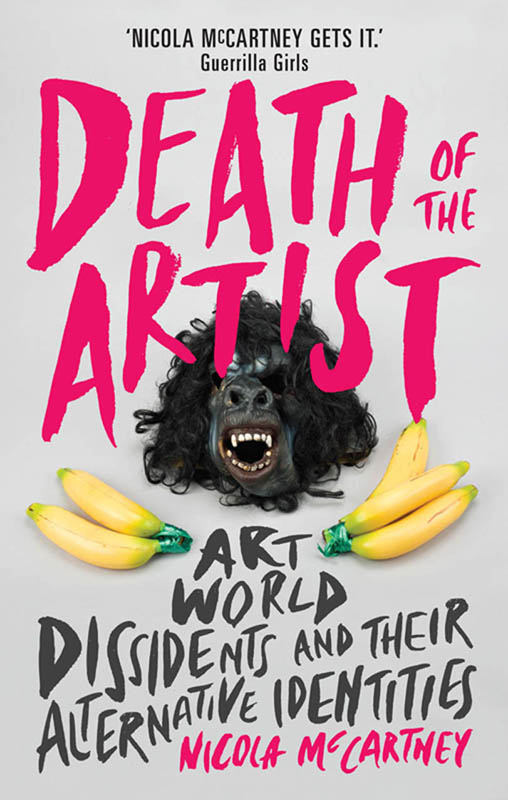

Nicola McCartney is an artist and educator. She is a lecturer in Cultural Studies at Central St Martins, University of the Arts London. She was previously Associate Research Fellow at Birkbeck, University of London, and has taught fine art and critical theory at The Sir John Cass Faculty of Art, Architecture and Design at London Metropolitan University. She is also a practising artist and has exhibited throughout London and the UK, received public commissions and undertaken residencies.

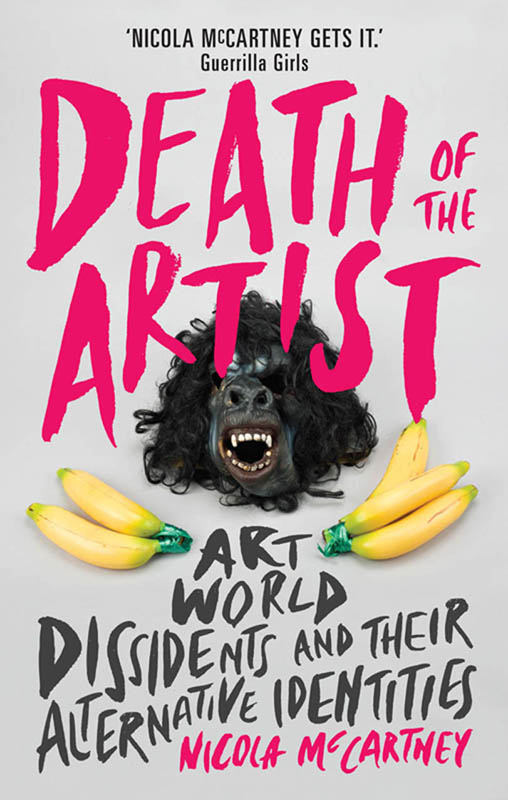

Nicola McCartney is part of a new generation of thinkers about art. Art now is more playful and indiscreet than it has ever been but it also aspires to talk to a political world that is both frightening but also where there is a possibility to reach new audiences. The idea of the artist in this new space is changing. In this book McCartney charts the careers of artists who question the role of the artist and who seek to subvert the notion that art is produced only by artists. McCartney asks: who do these artists think they are?

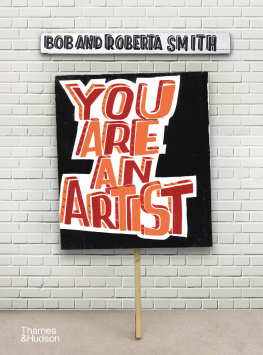

Bob and Roberta Smith

Nicola McCartney gets it: anonymous groups subvert the Western convention of the artist as a lone genius (usually a white male).

Guerrilla Girls

Nicola McCartney offers us a fresh and incisive analysis of moments in modern and contemporary art in which pseudonyms, anonymity, and collective identities are put to use. In doing so, McCartney interrogates the foundations of traditional art history and the art market. Death of the Artist is an important and exciting new contribution to our understanding of art's political efficacy.

Joanne Morra, Reader in Art History and Theory,

Central Saint Martins, University of the Arts London

Published in 2018 by

I.B.Tauris & Co. Ltd

London New York

www.ibtauris.com

Copyright 2018 Nicola McCartney

The right of Nicola McCartney to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by the author in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or any part thereof, may not be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Every attempt has been made to gain permission for the use of the images in this book. Any omissions will be rectified in future editions.

References to websites were correct at the time of writing.

International Library of Modern and Contemporary Art 26

ISBN: 978 1 78453 414 1 (HB)

978 1 78453 415 8 (PB)

eISBN: 978 1 78672 472 4

ePDF: 978 1 78673 472 3

A full CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

A full CIP record is available from the Library of Congress

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: available

For brave artists, especially those included here.

Contents

Interview: Socio-Art & The Art of Interaction:

James Early of LuckyPDF

Interviewed by Nicola McCartney on 9 May 2013

Interview: Feminist Avengers: Guerrilla Girls

Interviewed by Nicola McCartney on 14 August 2013

Performance and Collaboration:

No, Im Spartacus Chetwynd!

List of Figures

Man Ray, Belle Haleine, 1921. Gelatin silver print, 22.4 17.8 cm. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles. Man Ray Trust ARS-ADAGP.

Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore, 1928. Gelatin silver print, 11.8 9.4 cm. Courtesy of the Jersey Heritage Collections.

Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore, c.1928. Jersey Heritage Trust. Gelatin silver print, 12 9.4 cm. Courtesy of the Jersey Heritage Collections.

Man Ray, Marcel Duchamp as Rrose Selavy, c.19201. (1)(A). Philadelphia, Philadelphia Museum of Art. Gelatin silver print, 21.6 17.3 cm. Signed in black ink, at lower right: lovingly / Rrose Slavy / alias Marcel Duchamp [cursive]. The Samuel S. White 3rd and Vera White Collection, 1957. 2017. Photo: The Philadelphia Museum of Art/Art Resource/Scala, Florence.

Marcel Moore, 1930. Printed photomontage. Courtesy of the Jersey Heritage Collections.

Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore, c.1939. Jersey Heritage Trust. Gelatin silver print, 10.8 8.4 cm. Courtesy of the Jersey Heritage Collections.

Art & Language, Index 01, 1972, 8 filing cabinets, 48 photostats, 4 plinths. Installation dimensions variable. Collection Daros, Zurich. Art & Language? Courtesy Lisson Gallery.

Art & Language, Index: Incident in a Museum VI, 1986. Oil on canvas, 174 271 cm. Art & Language? Courtesy Lisson Gallery.

Ed Fornieles models, LuckyPDF s/s 2013. Photo: Oskar Proctor. Courtesy of LuckyPDF.

Chloe Sims, LuckyPDFs School of Global Art (TOWIEs Chloe Sims for the School of Global Art, featuring James Early and Chloe Sims). ICA, London, April 2012. Photo: Victoria Erdelevskaya. Photograph courtesy of James Early.

Original postcards sent from the Guerrilla Girls to artists asking them to agree to encourage their galleries to show more women and artists of colour. From Guerrilla Girls archive at Getty Research institute, LA, August 2013. Permission to reproduce granted by the Guerrilla Girls. Photograph taken by Nicola McCartney.

Guerrilla Girls, Guerrilla Girls Pop Quiz. 1990, 1995 Guerrilla Girls. Courtesy of the Guerrilla Girls.

Guerrilla Girls, Code of Ethics for Art Museums. 1989 Guerrilla Girls. Courtesy of the Guerrilla Girls.

A subscription request from a member of the public questioning the Guerrilla Girls varied rates for their journal Hot Flashes, found in the archives of the Guerrilla Girls, Getty Research Institute, LA. Photograph taken in August 2013. Permission to reproduce granted by the Guerrilla Girls. Photograph taken by Nicola McCartney.

Guerrilla Girls, Do Women Have to Be Naked to Get Into the Met. Museum? 1989, 1995 Guerrilla Girls. Courtesy of the Guerrilla Girls.

Bob and Roberta Smith, Dont Hate Sculpt (1997). Installation view, Chisenhale Gallery, 1997. Courtesy of Chisenhale Gallery.

The Art Party Conference 2013, presented by Bob and Roberta Smith on Saturday 23 November at The SPA, Scarborough. Photograph taken by Nicola McCartney at the event.

.

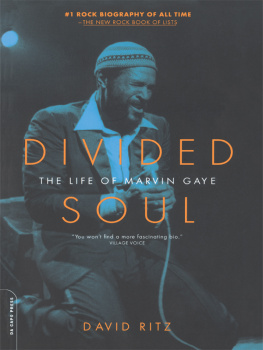

Bat Opera, Installation view, lower ground, Marvin Gaye Chetwynd (11 March26 April 2014, Sadie Coles HQ, London). Photograph taken by Nicola McCartney at the opening event of the exhibition.

Preface

Authorship is part of a discourse. How one attributes artists creations, the name they use, a chosen identity or whom else they might collaborate with can become complicated and political, a reflection of their time. The significance of who wrote a work, directed a film or spoke a poem varies by culture and history. Currently, the prevailing terrain of authorship in the commercial art world is that the signature still carries a lot of value and the personality of the maker contributes to our understanding of the cultural product. You might wonder, what does it matter? The work itself does not change. But authorship can make a difference. The novels authored by women in past centuries under male guises matter because they reflect socio-political times of oppression and their acknowledgement meant subsequent progress for womens emancipation. The films sold as a directors debut earn less because they attract fewer crowds. Art might be revered and sold for millions because it was made by a genius, who continues to haunt our galleries, retrospectives and histories, marginalising other artists, other cultures and concepts of art. This author thinks the traditional connoisseur is outdated; intellectual property and copyright is sacred yet, in the digital era, we appropriate and clash old with new media more than ever. We use apps to swap faces and mash up music, and photoshop is a verb. Our concept of authorship and its increasingly idiosyncratic and contemporary issues need to be updated. This project thus intends to reimagine artistic concepts of authorship and its current critique through a series of artists who complicate the debate with their identities and practices.

Next page