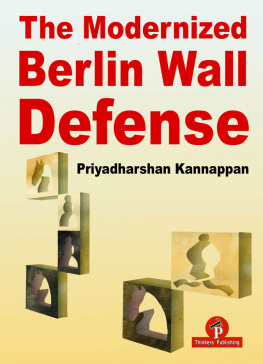

Free Berlin

Free Berlin

Art, Urban Politics, and Everyday Life

Briana J. Smith

The MIT Press

Cambridge, Massachusetts

London, England

2022 Massachusetts Institute of Technology

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher.

The MIT Press would like to thank the anonymous peer reviewers who provided comments on drafts of this book. The generous work of academic experts is essential for establishing the authority and quality of our publications. We acknowledge with gratitude the contributions of these otherwise uncredited readers.

This book was set in Arnhem Pro and Frank New by New Best-set Typesetters Ltd.

Publication of this book has been aided by a grant from the Millard Meiss Publication Fund of CAA.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Smith, Briana J., author.

Title: Free Berlin : art, urban politics, and everyday life / Briana J. Smith.

Description: Cambridge, Massachusetts : The MIT Press, [2022] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021045983 | ISBN 9780262047197 (hardcover)

Subjects: LCSH: Art and societyGermanyBerlinHistory20th century. | Avant-garde (Aesthetics)GermanyBerlinHistory20th century. | Art and societyGermanyBerlinHistory21st century. | Avant-garde (Aesthetics)GermanyBerlinHistory21st century.

Classification: LCC N72.S6 S538 2022 | DDC 701/.03dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021045983

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

d_r0

To the free cities of my youth, and the people I met there.

Contents

Introduction

Berlins Provincial Avant-Garde

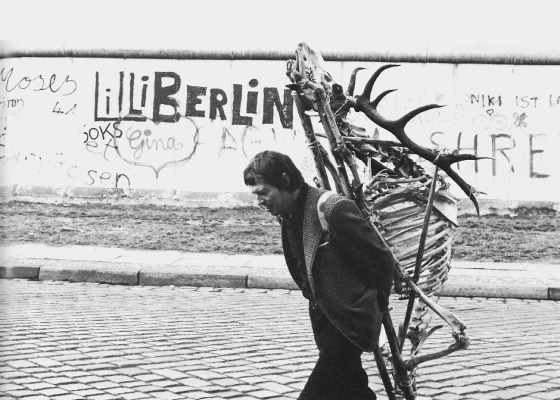

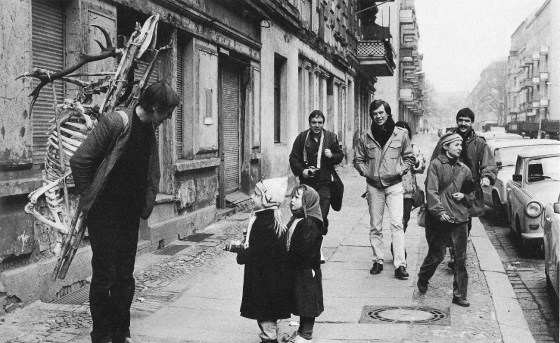

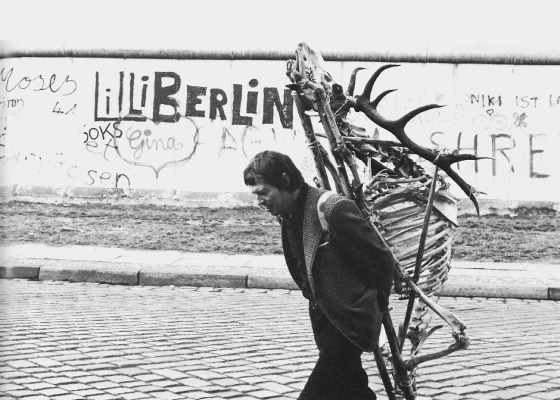

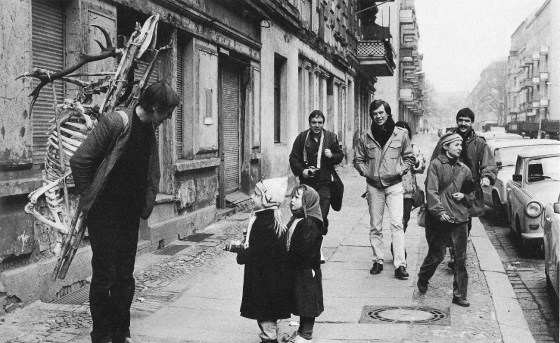

In the spring of 1984, Nikolaus Lang strapped a deer skeleton to his back and walked the streets of Berlin. The artist began in West Berlins eastern Kreuzberg district, where he followed the path of the Berlin Wall north and west toward the site of the former Nazi Gestapo headquarters on Prinz-Albrecht-Strae (figure 0.1). He ended his walk at the Checkpoint Charlie border crossing. The following day, Lang resumed his action in East Berlinhitching a ride across the border with a West German diplomat. Lang began his walk at Kollwitzplatz in the Prenzlauer Berg neighborhood, an area known for its large population of artists. A trail of curious onlookers formed behind him, as if he were the Pied Piper of Hamelin. West German critic Walter Aue later characterized Langs action as a symbol of rebirth and awakening life, and noted the skeletons role as a guide through the realm of the dead. It was also a great conversation starter, spurring encounters with children, dogs, elderly women, workers, and border guards (figure 0.2).

Although Lang was a visiting artist from Bavaria, his two-day art action, Showing the City to the Stag, was of a wholly local vintage. Within the geopolitical anomaly of Cold War Berlin, located some 100 miles behind the Iron Curtain and divided between two rival ideologies, artists on either side of the Berlin Wall pursued their own exceptions to the rule. Rather than being housed in museums and galleries, these artists asked, what if art was everywhere? Rather than limited to elite practitioners, what if art was an everyday activity for everyone to participate in? What if moments of social exchange and dialogue were works of art? What if art could make people smile, laugh, and think more critically about the world around them?

Figure 0.1

Nikolaus Lang, Showing the City to the Stag, West Berlin, 1984. Knstlerhaus Bethanien Berlin, 1985. Photographer unknown.

Figure 0.2

Nikolaus Lang, Showing the City to the Stag, East Berlin, 1984. Knstlerhaus Bethanien Berlin, 1985. Photographer unknown.

Free Berlin introduces readers to the individuals and collectives who raisedand answeredthese questions during Berlins final two decades of division, and continued to do so after the citys reunification in 1990. It reveals the emergence of an egalitarian and socially engaged visual culture in the divided city that elevated art and creativity as an essential component of civic life. This book argues that this visual culture was equally formative of the citys durable tradition of participation, civic engagement, and lively urban agitation. The art unleashed within the quotidian spaces of divided Berlin invited residents to consider how other areas of urban space might be remade, or reclaimed, through their own actions. These impulses live on in contemporary Berlin: fueling artists resolve to work outside the market and organize in solidarity, and residents vigorous defense of green spaces, affordable housing, and collectivist projects from capitalist incursions.

In an account of her own Prenzlauer Berg tour, East German writer Daniela Dahn described encountering Nikolaus Lang and his train of followers, who included the East Berlin action artist Erhard Monden (figure 0.3). This may come as a surprise to readers who are more familiar with characterizations of both East Berlin, the capital of the German Democratic Republic (GDR), and the walled city of West Berlin as gray, bleak, and hostile. Dahns comment and Langs walk hint at the local color hidden just beneath the surface, and the need for historical revision.

Figure 0.3

Nikolaus Lang, Showing the City to the Stag, East Berlin, 1984. Erhard Monden, back left with camera. Knstlerhaus Bethanien Berlin, 1985. Photographer unknown.

Free Berlin sets out to recover these everyday peculiarities, collective joys, and grassroots provocations. This granular perspective offers a new understanding of the divided city as the site of both limitations and vast possibilities. Readers will encounter a largely forgotten world of artists and art collectives who turned to art as a stimulus for imagining new forms of social and artistic life in the city. These artists suggest how the citys state of exception invited detours from artistic traditions that carefully distinguished between art and non-art, or the artist and the dilettante. These detours reveal paths leading toward the adoption of a more capacious role for art in our own lives, cities, and societies. Accessing this history at street level, readers are invited to tag along with these artists as they traverse the city center and peripheries, ruins and aging industrial infrastructures, consumer hubs and major tourist sites, amid the citys final decades of division and transformation to the reunified German capital. Along the way, distinctions between art, politics, and everyday life will become increasingly blurred.

Unlike Nikolaus Lang, who returned to his artistic career in Bavaria following his two-day sojourn through Berlin, most of the individuals and art collectives featured in this book are unknown to art historians. Many prefer it that way, and willingly extracted themselves and their work from the system of individuals and institutions traditionally responsible for bestowing artistic value: galleries, curators, collectors, and critics. Instead, they pursued a more direct relationship with society. This involved relinquishing bourgeois notions of career advancement or making a name for oneself in favor of collaborative, participatory, and anonymous practices. This book is not a belated attempt to bring these artists to the attention of art-world influencers. Instead,

Next page