The right of John Fairley to be identified as the Author of this Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Pen & Sword Books Limited incorporates the imprints of Atlas, Archaeology, Aviation, Discovery, Family History, Fiction, History, Maritime, Military, Military Classics, Politics, Select, Transport, True Crime, Air World, Frontline Publishing, Leo Cooper, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing, The Praetorian Press, Wharncliffe Local History, Wharncliffe Transport, Wharncliffe True Crime and White Owl.

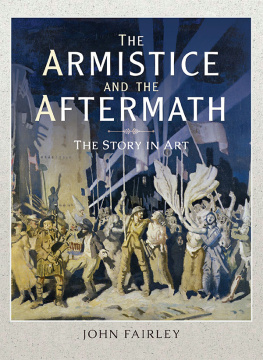

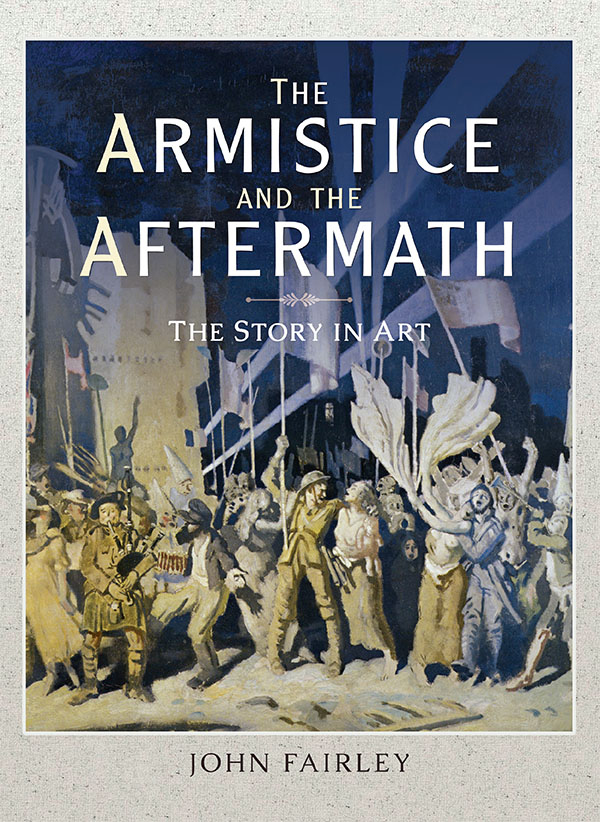

Armistice , 1918, Pierre Bonnard.

Chapter One

Peace at Last

Pierre Bonnards painting of Armistice night in Paris in 1918 is the most joyous picture of the most joyous day in the twentieth century. All the colour and verve of this most passionate of Impressionist artists is devoted to a scene of happiness and relief, yet it also seems to evoke the memory of the killings and carnage which had only ceased that very morning. The beautiful girl at the centre of the painting, entranced, it would seem, by the celebrations around her, perhaps also reflects a consciousness of the dreadful events of the last four years.

But for the men in the foreground, indeed the whole of the rest of the exuberant crowd, there are, it seems, no such inhibitions. The dancers and the diners are flinging themselves into the pleasures of peace. There are watchers at every window. The total blackness recedes and the bright blues and reds assert the confidence of that unique night.

It is in the poems and the paintings that the First World War stays in the minds and imagination of present generations. The painters were there at the heart of great events. So too were the poets, putting into words what the painters depicted on canvas. And both of them trying to illuminate what was happening in the aftermath of war.

Wilfred Owen was to die only seven days before the Armistice while his regiment was crossing the Sambre Oise canal as part of the assaults which were to finally convince Ludendorff and the German generals that they had to sue for peace. He left behind a poem that has continued to arouse emotions a hundred years on:

Move him into the sun

Gently its touch awoke him once

At home, whispering of fields unsown

Always it woke him even in France

Until this morning, and this snow

If anything might rouse him now

The kind old sun will know.

Think how it wakes the seeds

Woke, once, the clays of a cold star

Are limbs so dear achieved, are sides

Full nerved still warmed too hard to stir?

Was it for this the clay grew tall?

O what made fatuous sunbeams toil

To break earths sleep at all?

Wilfred Owen, like his friend and inspiration Siegfried Sassoon, had been wounded and yet gone back to war.

When the guns fell silent, Siegfried Sassoon wrote what was to become the Anthem of the Armistice.

Everyone suddenly burst out singing

And I was filled with such delight

As prisoned birds must find in freedom

Winging wildly across the white

Orchards and dark green fields, on, on, and out of sight.

Everyones voice was suddenly lifted

And beauty came like the setting sun

My heart was shaken with tears; and horror

Drifted away. O, but everyone

Was a bird and the song was wordless; the singing will never be done.

Sassoon, wounded once more in July 1918 and shipped back to England, had felt an intense longing to be back at the Front with his company There at least I had been something real, and I had lived myself into a feeling of responsibility for them. All that was decent in me disliked leaving them to endure what I had escaped.

In the first days of November, Sassoon had found himself recovered enough to rejoin the literary world, of which he was already a star. He met Winston Churchill, Full of victory talk, and just off to a War Cabinet meeting. The next day, he took a train down to the West Country to stay with Thomas Hardy, who told him that in 1914 he feared more than anything else that English literature might be wiped out by the Germans. Then it was back to Oxford to meet John Masefield. Sassoons diary for November 11 reads:

I was walking in the water meadows by the river below Cuddesdon a quiet grey day. A jolly peal of bells was ringing from the village church, and the villagers were hanging little flags out of the windows of their thatched houses. The war is ended. It is impossible to realise. Oxford had much flag waving also.

I got to London about 6.30 and found masses of people in streets and congested Tubes, all waving flags and making fools of themselves an outburst of mob patriotism. It was a wretched wet night and very mild. It is a loathsome ending to the loathsome tragedy of the last four years.

Robert Graves, recovered from wounds sustained at the Battle of the Somme, was at a camp in Wales when the Armistice came The news sent me out walking along the dyke above the marshes of Rhuddlan, cursing and sobbing and thinking of the dead.

The artists and poets coming back from the war brought its horrors with them in their minds. As Graves wrote, Shells used to come bursting on my bed at midnight. Strangers, in daytime, would assume the faces of friends who had been killed.

One of the most notable official war artists, Christopher Richard Nevinson, a wounded veteran who had painted La Mitrailleuse and Passchendaele, was in London that day when the news came through. He wrote:

For me, Armistice Day will always remain the most remarkable day of emotion in my life. When we heard the cheers outside, I dropped my brushes and rushed out with Kathleen. We jumped on a lorry which took us down to Whitehall. Here we saw Winston Churchill beaming on a mob that was yelling itself hoarse. With a thousand others in Trafalgar Square we danced Knees Up Mother Brown, then to the Caf Royal for food, where we were joined by a gang of officers and drank a good deal of champagne, and raided the kitchens because the staff had knocked off work. Then on to the Studio Club to find a crowd of demi-intellectuals terribly calm and indifferent to the noise of the multitude, and some of them even apprehensive as they saw the end of their well-paid jobs. Back into the streets to rejoice with human beings. And back again to the Caf Royal: poor Kathleen with an American cocotte lying over her knees crying, and another girl sobbing because no one was cheering for Serbia though she came from Birmingham. A crowd of journalists, including Scott of the Manchester Guardian, who, for no reason at all, was bitten by a French girl, who then bit me.