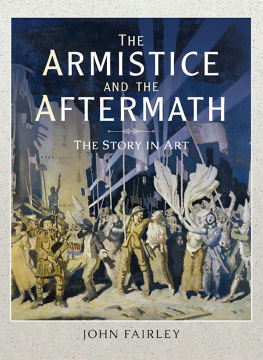

First published in Great Britain in 2015 by

Pen & Sword Military

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright John Fairley 2015

ISBN: 978 1 47384 826 9

PDF ISBN: 978 1 47384 829 0

EPUB ISBN: 978 1 47384 827 6

PRC ISBN: 978 1 47384 828 3

The right of John Fairley to be identified as the Author of this Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Typeset in Ehrhardt by

Mac Style Ltd, Bridlington, East Yorkshire

Printed and bound in India by Replika Press Pvt. Ltd.

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of Pen & Sword Archaeology, Atlas, Aviation, Battleground, Discovery, Family History, History, Maritime, Military, Naval, Politics, Railways, Select, Transport, True Crime, and Fiction, Frontline Books, Leo Cooper, Praetorian Press, Seaforth Publishing and Wharncliffe.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Acknowledgements

My thanks go first to the individuals and institutions named in the picture credits who have looked after and sought out for us these works of art, which have been largely hidden away for so long.

Then to the compilers of the many regimental histories, which contain the best available detail of the experiences of horsemen in the war. The war museums of the Empire also contain the most valuable personal testimonies.

In the vast literature on the Great War and the splendid London Library has an entire floor devoted to the conflict acknowledgement must be paid, above all, to the late Marquis of Angleseys lifelong devotion to restoring the reputation of the cavalry, and to the cohort of vets who put together the great authoritative official history of the animals recruited into service in the war, of the care they received and the fates that overtook them.

On a personal note, Henry Wilson of Pen & Sword has been unstinting in his encouragement, Sian Phillips of Bridgeman Art has been tireless in helping me track down these pictures, and George Chamier a perceptive and supportive editor.

Preface

In the Canadian War Museum in Ottawa there is this extraordinary painting of a cavalry charge. The horses hurtle forward in disciplined lines. The glistening threat of the sabres is thrust across the canvas. Men have already been hurled out of the saddle. Horses, too, are stumbling to the ground.

For all the world, this could be a companion piece to Lady Butlers famous painting of the charge of the Scots Greys at Waterloo. But there are clues to its difference. The uniforms are khaki, not royal red; the headgear is trench tin helmets, not dragoon casquettes; there are bandoliers of bullets. For this is taking place more than a century after Lady Butlers scene. It is Alfred Munnings picture of the Canadian Strathconas Horse, with Lieutenant Gordon Flowerdew in the foreground leading the charge in March 1918 which halted what had been until then the remorseless advance of the great German spring offensive.

By 1918 the Great War had spawned a vast array of new lethal technology. The tank had made its debut across the trenches and no-mans-land of Flanders. There was gas, and underground mines. Aircraft were fighting each other in the skies and dropping bombs on enemy lines. Armoured cars had appeared. The artillery had developed massive guns with huge range and great accuracy. The machine gun had reached a new and implacable rapidity.

It is scarcely credible then that the great German assault of 1918, so close to achieving decisive success, should have been turned at a key point by the means portrayed in Munnings painting cold steel on horseback.

Lieutenant Flowerdew was to die in the battle, shot through both legs and the chest but, to the last, urging his men on with the cry Carry on boys! We have won. He was awarded the Victoria Cross.

The battle at Moreuil Wood was the last throw in an attempt to close the gap between the British and French lines, thus preventing the Germans crossing the River Avre and breaking through to Amiens and the coast. Flowerdew had led his Strathconas Horse at full gallop against a phalanx of machine guns, rifles and artillery and cut right through them, then turned and continued to sabre the remaining enemy. The Strathconas lost two thirds of their men and horses. But the German advance was halted.

Munnings painting is the most spectacular refutation of the myth that the cavalry played no significant part in the Great War. Alfred Munnings had spent the winter and early spring of 1918 with the Canadian cavalry. Already blind in one eye and rejected by his Army medical board, he had been recruited by his artist friend Cecil Aldin into the Army Remount Service and from there was enlisted by Paul Konody, the Observer art critic, on behalf of the Canadian Government, to go out to France with their cavalry. He was with them through the monthlong March retreat, but still managed to create more than twenty pictures.

The Charge of Flowerdews Squadron, Sir Alfred Munnings. (Canadian War Museum, Ottawa, Canada/Bridgeman Images)

After the Recapture of Bapaume, Christopher Nevinson. (Rochdale Art Gallery, Lancashire, UK/Bridgeman Images)

Munnings appointment was part of a concerted effort by the British and Imperial governments to create a record of the war, with correspondents and artists selected and dispatched to almost all the theatres of war. Many of the painters had been distinguished equestrian artists, and it was inevitable that their eye was caught by the hundreds of thousands of horses meeting the demands of the various campaigns, whether in France, the deserts of Mesopotamia or the assault on the German colonies in Africa.

The first two official war artists were only appointed in April 1917, nearly three years into the conflict, in the wake of the growing sentiment that painters at home were not doing justice to the nature of the conflict. James McBey was sent out to Egypt, where he became attached to the Australian horsemen and produced some of the epic paintings of the desert war. William Orpen was sent to France. That same summer, two artists who had served at the Front and whose reputation was to be made by their war work, Paul Nash and Christopher Nevinson, both exhibited in London. Within weeks, along with Sir John Lavery and Eric Kennington, they were sent back to France as official artists. They were joined by Munnings and in the end by a score of other artists, including George Clausen and the intensely emotional Lieutenant Harold Septimus Power, who was attached to the Australian forces in France. His Bringing up the Guns became one of the most reproduced pictures of the War.

In the remaining fearful months of the War these painters produced the great body of work which records the courage and suffering not only of the men but also of the horses who endured so much alongside them.