Table of Contents

Guide

Page List

Literary Awakenings

Copyright 2017 by Syracuse University Press

Syracuse, New York 13244-5290

All Rights Reserved

First Edition 2017

17 18 19 20 2122 6 5 4 3 2 1

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

For a listing of books published and distributed by Syracuse University Press, visit www.SyracuseUniversityPress.syr.edu.

ISBN: 978-0-8156-3487-4 (hardcover) 978-0-8156-1078-6 (paperback)

978-0-8156-5385-1 (e-book)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Available from the publisher upon request.

Manufactured in the United States of America

To my parents, George and June Koury, with love

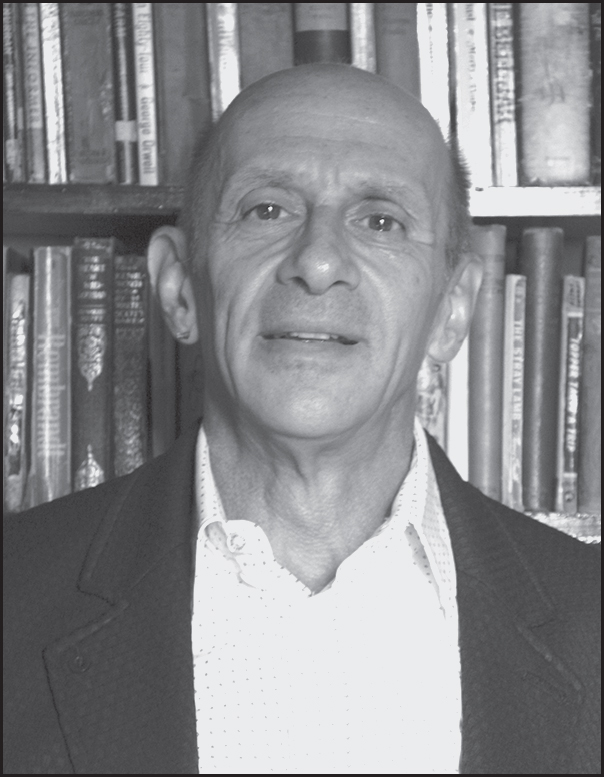

Photograph by Jane Bishop

Ronald Koury, a graduate of Columbia College with a degree in English, joined the Hudson Review in 1981 and has been its managing editor since 1985. He has been a speechwriter for the delegation of the Permanent Mission of the Kingdom of Bhutan to the United Nations. He lives in New York.

Contents

| RONALD KOURY

| WILLIAM H. PRITCHARD

| JEFFREY HARRISON

| ANTONIO MUOZ MOLINA

Apt Admonishment

Wordsworth as an Example | SEAMUS HEANEY

| ANDREW MOTION

| LOUIS SIMPSON

| WENDELL BERRY

| DAVID MASON

| CLARA CLAIBORNE PARK

Before I Read Clarissa I Was Nobody

Aspirational Reading and Samuel Richardsons Great Novel | JUDITH PASCOE

| DANA GIOIA

| IRVING SINGER

| BARBARA KRAFT

Prophet against God

William Empson (190684) | GEORGE WATSON

Whos Afraid of Virginia Woolf?

A Memoir | RICHARD HORNBY

| IGOR WEBB

| JOYCE ZONANA

| THOMAS M. DISCH

| SUSAN BALE

| JOSEPH EPSTEIN

Preface

RONALD KOURY

Around thirty years ago, the editors of the Hudson Review began to notice a new trend in literary criticism. Many of the best literary essayists and reviewers were sending us critical work written in a highly personal manner. They read like memoirs; in fact, some were clearly memoirs but literary criticism at the same time. This was in marked contrast to the theoretical, technocratic work that prevailed in many literary and academic venues, and in many places still does. We found these essay/memoirs refreshing. As time went on, the Hudson Review became a home for this kind of accessible, memoirist writing.

This collection features some of the best examples of this combination of personal impressions with literary criticism. The chaptersAwakening to Literature, Students and Teachers, Tributes, and Facing the Textexplore many facets of this theme. In the end, what unites these diverse contributions is the joy of appreciation, the pleasures of engaging with literature.

Pleasure is a loaded word in our culture; the very concept of it is, even today, suspect. The essays in this collection do not disappoint in that respectall are lively and full of surprises, some, even subversive.

I owe an enormous debt to many people whose work was essential in the creation of this book. First and foremost to Paula Deitz, editor of the Hudson Review, who helped me every step of the way with invaluable advice and encouragement. Every day, I learn from her, her input with this book being a prime example. I have always looked up to longtime Hudson Review advisory editor William H. Pritchard, so I was honored when he agreed to write the introduction, which is a tribute to the collection. To my colleagues at the magazine, Zachary Wood, associate editor; Eileen Talone, assistant editor; and editorial interns William Grosholz Edwards, Jessica Lucia Pacitto, and Bates W. Crawford, I am extremely grateful for proofing and preparing the manuscript. Everyone at Syracuse University Press was a joy to work with: Deborah Manion, acquisitions editor; Lisa Renee Kuerbis, the marketing coordinator; Lynn P. Wilcox, design specialist, whose beautiful cover so enhances the book; Ann Youmans, copy editor; Kay Steinmetz, editorial and production manager; Kaitlin Busser, editorial assistant. Deepest appreciation to Michael A. Boyd and his generosity in supporting this anthology. Of course, the writers are what make the bookmy enormous thanks to each of them.

Introduction

WILLIAM H. PRITCHARD

Among the memorable formulations in Wordsworths great preface to Lyrical Ballads, 1798, one may serve to characterize a common spirit in the essays collected here. His formulation attempts to define and celebrate what the Poet is and does:

He is the rock of defense for human nature, an upholder and preserver, carrying everywhere with him relationship and love. In spite of difference of soil and climate, of language and manners, of laws and customs, in spite of things silently gone out of mind, and things violently destroyed, the poet binds together by passion and knowledge the vast empire of human society, as it is spread over the whole earth, and over all time.

Twenty-eight years old when he composed this preface, the young Wordsworth calls upon his resources of eloquence and inclusiveness to conjure up this vision of universal strength and sympathy that, he believes, informs his and Coleridges collection of poems. Never before in English criticism had such claims been unapologetically put forth.

These essays by contributors to the Hudson Review are naturally pitched in a lower key, and their concerns are pointed in many directions with no obviously central theme uniting them. But although theme is too inclusive a word for what binds them together, there is a pervading spirit that, while not to be confused with Wordsworths matchless evocation of the Poet, is nevertheless comparable to it. Calling the spirit literary awakenings invites questions, since immediately the sophisticated reader, perhaps a professor of English, asks to know whats gained by evoking literary, an old-fashioned word that must earn its keep if its to have reputable value.

In the final item of this book, the veteran writer of familiar essays, stories, and biographical evaluations, Joseph Epstein, coming to the end of his essential, if impossible, attempt to locate the pleasures of reading, suggests that wide reading over time would or ought to confer on one the literary point of view. He puts it in quotes, as if to assure us that he knows how slippery a subject hes taken on, but proceeds to make perhaps the very least claim that can be made about the subject: that the literary point of view teaches a worldly-wise skepticism, which comes through first in a distrust of general ideas. And he quotes with approval Ortega y Gasset: As soon as one creates a concept, reality leaves the room. But Epstein doesnt merely endorse a healthy skepticism about general ideas as the final reward of wide reading; instead he has the temerity to insist that the literary point of view teaches us profoundly, and that what it teaches is the richness, the complexity, the mystery of life. Such a claim invites further derision from the sophisticated: mystery, richness, complexitywhat are these words but an admission that the product of wide reading is beyond words, beyond the resources of language altogether? Yet in a slightly different vocabulary, Wordsworth would have known and approved of what Epstein is advocating, and he would have sympathized with his essays title, The Pleasures of Reading, since for Wordsworth the production of pleasure was the first and last task of the poets art: It is a homage paid to the native and naked dignity of man, to the grand elementary principle of pleasure, by which he knows, and feels, and lives, and moves.

Next page

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.