Table of Contents

Guide

Table of Contents

for Sylvia Ardyn Boone (19411993) & Robert Farris Thompson

who taught me what I knew to be true

FOREWORD

HENRY LOUIS GATES, JR.

There are 40 million black people in this country, and there are 40 million ways to be black. Some might take this claim of radical individuality as somewhat nave. The Princeton scholar Eddie S. Glaude, Jr. points out that such a formulation runs the risk of being a little too easy (he called similar thinking pimply faced in a recent lecture), in that it addresses the lives of black persons, but not of the black people.

When I gesture toward the myriad ways to be black, to act black, to feel black, I do not mean to suggest that we are all of us in our own separate boxes, that one black life bears no relation to another. Of course not. We are not a monolith, but we are a community. And the members of a community talk to each otherand talk about each other.

This book that Rebecca Walker has so creatively put together, Black Cool: One Thousand Streams of Blackness, is a compelling and sustained conversation about the multiple meanings of blackness in the United States today. In this brilliantly conceived and edited volume, we see a multiplicity of ways in which blackness is both definitive and interpretive, confining and liberating, imposed and embraced, perceived and, even at times, ignored. The essays in this volume encourage us to hold two seemingly contradictory ideas in our minds at once: On the one hand, blacks as a group share culture, language, and experience that join us inextricably together, but as individuals, we may well act in our own self-interest, without regard to the needs of the community.

In other words, it is a simple fact that sometimes we define ourselves in terms of each other, and sometimes we do not. The seminal essays in this volume show us, in careful and thoughtful detail, that it remains necessary and productive for African Americans to have a continuing conversation about this simple fact. This is a superbly edited collection, and constitutes a major contribution to our understanding of what we might think of as the fundamental problem for African Americans in the twenty-first century: how class differentials within the race compound individual experiences of anti-black racism, and ever more profoundly shape what it means to be black itself.

INTRODUCTION

REBECCA WALKER

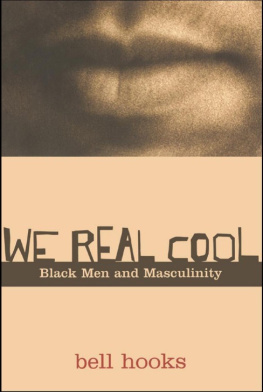

This book began to write itself many years ago, when I was a student at Yale and had the good fortune to study with three extraordinary human beings: art historian and anthropologist Sylvia Ardyn Boone, cultural critic and feminist icon bell hooks, and Robert Farris Thompson, a pioneer who has spent his life identifying, cataloguing, and excavating what we now call the Afro-Atlantic aesthetic tradition.

I grew up around this tradition. The mark of Africa was always in our home, mediated through the African-American artistic lens in photographs, books of poetry and prose, my mothers garden, and the music of Stevie Wonder and John Coltrane. But even as a young girl, certain things held my eye longer than others; some objects demanded to be touched, held, examined, apprehended with greater care than others.

There were chairs. In almost every room, my mother left a seat, a potential throne, open, and waiting for a visitor to come, human or spirit, whatever shape or form. There were even pictures of chairsin my mothers study, a Modigliani painting of a girl in a tall chair watched from above her desk. On the wall in the hallway, another painting of a chair: empty, red. In the living room, a long wooden bench of walnut, an old church pew. Leaving a space for spirit: a trope of West African ritual.

Quilts were carefully spread over beds in our house, and often admired for their design, color, or size of stitch. Intricate composition and surprising use of color held the cultural recognition of the value of cloth, the wealth that is both beauty and dowry, but also screamed the signature of the artist, who, through audacious aesthetic choices, asserted a profound authenticity and thus resistance to all that would rob her of subjectivity. As in many examples of African art, patterns often featured the zag, the break, chevron-like symbols that seemed to come directly from the cloths of West African art.

At my uncles home, cars filled the driveway, and sometimes the front yard, too. In West Africa, the Yoruba worship Ogun, the god of iron and war. In antebellum America, enslaved Africans were known for their blacksmithing skills, and forced to forge the iron of their own shackles because of it. In contemporary African-America, isnt a reverence for metal, that which comes from the very core of the earth and represents strength in the face of all obstacles, visible in the driveways of my uncles?

At my grandmothers house in rural Georgia, family photos spread like kudzu to cover the wall above her favorite chair in her living room. This massive display was nothing less than a symbolic manifestation of the power of kin.

And then there was the bath. While my mother or I soaked, the other would sit on the floor alongside the tub and tell the news of the day. After, coconut oils and amber potions were sampled, and more talking. Looking at our reflections in the mirror, laughing and sharing thoughts, my mother and I birthed ways to see the world and our places in it; we grew through those conversations, we became.

Like the Mende women Sylvia Boone so lovingly describes in her book Radiance from the Waters, my mother and I entered the space of cleansing waters and emerged renewed and radiant. Neku, the Mende call it. Beautiful. Fresh.

Cool.

I did not question these objects and rituals, or the others that marked our days, until I began to study art and aesthetics three thousand miles away from home, inside of cold, neo-gothic buildings stripped bare of color and heated with hard radiators that burned my fingers when I reached out to them for warmth. I knew then I had been in the presence of something else before I arrived in that icy city, which both fed my mind and chipped away at my spirit.

When I began to study with Boone, Thompson, and hooks, I learned in words what I had only known in feeling. They spoke of the other place, the other language I had left behind. Through their work, these teachers taught me that the language of my home came from a people whose names had been erased, whose tongues had been cut from their mouths, whose traditions had been deemed punishable by death. But, these teachers said, those people had not surrendered because their code was so deeply embedded in them, the specific contours of their humanness could not be vanquished.

My uncles taught me about heaps of metal that could take me where I needed to go. My grandmothers wall demanded I pay attention to ancestry, kin. The quilts taught me how to put shards, remains, and scraps of both the material and psychic worlds together to make myself a shield, a protective coat of arms. My mother taught me how to enter the bath an ordinary woman, and emerge a queen.

I began to see the fingerprints of Africa everywhere.

I was captivated in the same way by an image of President Obama during the election season of 2008. Once I put it on my wall and continued to look, this book continued to call itself into being, to knock on the door of my studio and demand to take its place in the empty chair I leave, always, beside my desk.