The Origins of Cool in Postwar America

Joel Dinerstein

The University of Chicago Press

Chicago and London

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2017 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations in critical articles and reviews. For more information, contact the University of Chicago Press, 1427 E. 60th St., Chicago, IL 60637.

Published 2017

Printed in the United States of America

26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-15265-3 (cloth)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-45343-9 (e-book)

DOI: 10.7208/chicago/9780226453439.001.0001

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Dinerstein, Joel, 1958 author.

Title: The origins of cool in postwar America / Joel Dinerstein.

Description: Chicago ; London : The University of Chicago Press, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016049319 | ISBN 9780226152653 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780226453439 (e-book)

Subjects: LCSH: Popular cultureUnited StatesHistory20th century. | United StatesSocial life and customs19451970. | Cool (The English word)

Classification: LCC E169.12 .D566 2017 | DDC 306.0973/0904dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016049319

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

To Dave and Kenny, the cool men I grew up with

Contents

Figure 1. Miles Davis in Paris with Juliette Grco, the muse of the existentialists, in 1949 ( Jean-Phillipe Charbonnier, Getty Images).

Paris, 1949

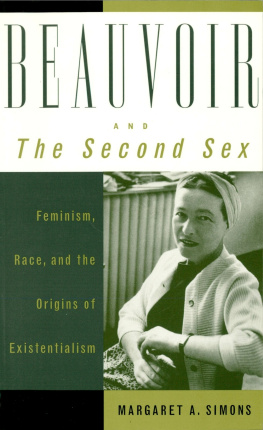

Boris Vian had been trying to orient the ears of Sartre and Beauvoir to bebopthe new jazz idiomfor three years. A year earlier, Dizzy Gillespie and His Orchestra thrilled the group with their precision, humor, and drive, all played without charts that had been misplaced. The night before, the circle had gone to the festival to hear Charlie Bird Parker, Vians favorite, one of the gods come to visit us on earth, he wrote in Jazz Hot, a God and a half! Charlie Parkers single, Cool Blues, had won Frances Grand Prix du Disque (best record) of 1948.

Earlier that evening the group had seen a quintet led by the young Miles Davis, featuring the pioneering bebop drummer Kenny Clarke. During the set, Miles espied Juliette Grco in the audience, dressed in her usual black, glowing without a spotlight. On a set break, he beckoned her onstage with an index finger. They did not have a common language, yet mimed their way through a set of flirtations about music and voice using the trumpet as a prop and fell into love at first sight.

They spent a week together. Grco thought Miles had an expressive manner like a Giacometti sculpture, a face of great beauty. Miles loved Grcos style, autonomy, and charisma, her minimalist sense of expression, the plasticity of her face, and lithe body. Later that year, Miles Davis would record the Birth of the Cool sessions. Grco was on the verge of a successful singing career that would eclipse her film roles.

Why dont you two get married? Sartre asked Miles later that same week. He could stay in France, Sartre appealed, perhaps thinking of the author Richard Wright and his wife Ellen, close friends of existentialisms first couple. Wright became a French citizen in 1947; James Baldwin had just moved there and joined the African-American expatriate group of artists in postwar Paris.

I cant do that to her, Davis thought but said aloud: I love her too much to make her unhappy. Davis did not have to state the obvious. Both Sartre and Beauvoir had written eloquently about racial oppression in the United States. And its much worse for white women married to black men, Davis added. Grco recalled Davis telling her, Youd be seen as a negros whore in the US... and this would destroy your career. And yet, and yet... to live in France and marry this woman, to feel the freedom, equality, and sense of belonging hed never felt even as a middle-class black kid in St. Louis? It was tempting. I had never felt that way in my life... the freedom of being in France and being treated as a human being, like someone important. Like an artist. Yet Davis also intuitedrightly, it turned outthat if he lived in France, he would lose touch with the currents of his art, with his fellow artists, with his country, and with jazzs social and ethnic content.

So he left on schedule, heartbroken. Davis and Grco saw each other in Europe now and then, especially in Paris, when he was touring. Five years later, Grco toured the United States and invited Davis to dinner at the Waldorf Astoria in New York, where African-Americans were unwelcome. Grco recalled: After two hours [of waiting], the food was more or less thrown in our faces. The meal was long and painful, and then he left. Later that night, Miles Davis called in tears and told Grco never, ever to ask to see him again on American soil. The experience proved him prescient.

When he toured Europe in 1957, Miles Davis played the Club Saint-Germain, where drummer Kenny Clarke was now the musical director, having joined the considerable African-American expat community in Paris. That night at the club, Davis met director Louis Malle, who hired him on the spot to provide a score for his first movie, a film noir called Elevator to the Gallows (Lascenseur pour lchafaud, 1958). Davis was only going to be in Paris for a few days but took the job anyway.

Davis hit on a simple, brilliant method to score the film: the musicians watched the rushes and improvised the music to the action. Miles called out when and where to stopcomposing, arranging and playing only to those images best enhanced by music. Other scenes were left to run without music. To watch the film now, the soundtrack still deftly evokes nighttime in postwar Paris, the vibrating tension of a man in the midst of a criminal act, an agitated woman walking through the crowds of a busy boulevard. The musicians finished recording the soundtrack in one overnight session.

The effectiveness of this soundtrack as ambient music for interior psychic moods points up an artistic tragedy: that in Jim Crow America, black jazz musicians were excluded from Hollywood, as composers, musicians, and even in studio orchestras. Jazz musicians would have been the natural composers for the genre of film noir. But there is one minor consolation: Daviss experience of improvising music to visual images helped trigger his next musical phase to the modal jazz of Kind of Blue (1959). Every Miles solo on the recordby far the best-selling jazz album of all timecan be heard as a scene in an unmade film noir. By 1959, Miles was an icon of cool and his quintet with John Coltrane was a gathering place for artists and celebrities: Marlon Brando and Ava Gardner often came together, and the audience often included Tony Bennett, Elizabeth Taylor, James Dean, Lena Horne, Frank Sinatra, and boxer Sugar Ray Robinson.

Like every artist, Miles Davis built his music from disparate artistic influences. In the 1950s, Daviss sonic signature was his spare, precise melodic phrasing on the muted trumpet. By his own admission, it owed a debt to Frank Sinatras cadences and something as well to Orson Welless radio voice. In the same year as Daviss visit to Paris1949Welles was In fact, he cast her as Helen of Troy in

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).