The Mandarins

Simone de Beauvoir

Translated by

Leonard M. Friedman

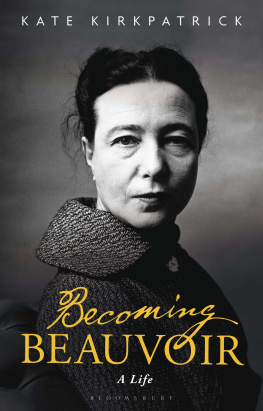

Simone de Beauvoir was born in Paris in 1908. She took a degree in philosophy at the Sorbonne in 1929, and was placed second to Jean-Paul Sartre, with whom her name was to be inextricably linked for the next fifty years. De Beauvoir taught in Marseilles and Rouen during the 1930s and in Paris during the war. After Liberation she emerged as one of the leading figures of the Existentialist movement and, with Sartre, Camus and many others, was to set the course of Left Bank intellectual life for many decades there after. Simone de Beauvoir's first novel, She Came to Stay, was published in 1943. The book explored a woman's quest for moral and intellectual self-determination, a theme which was to run throughout all her work. Author of six novels, de Beauvoir won the prestigious Prix Goncourt in 1954 for The Mandarins. The Second Sex, her classic account of the status and nature of women, was published in 1949; hugely influential, it confirmed de Beauvoir's role as a pioneer in the development of post-war feminism. Her other writings include her four-volume autobiography,

Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter, The Prime of Life, Force of Circumstance and All Said and Done, and a moving account of her relationship with her dying mother, A Very Easy Death. In her later years de Beauvoir was actively involved in many socialist and feminist causes, and in 1975 was awarded the Jerusalem Prize for 'writers who have pro moted the concept of individual liberty'. She died in 1986.

Harper Perennial

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

77-85 Fulham Palace Road

Hammersmith

London W6 8JB

www.harperperennial.co.uk

This Harper Perennial Modern Classics edition published in zoos

Previously published in paperback by Flamingo 1993 (as a Flamingo Modern Classic)

and 1984 (reprinted five times)

First published in France in 1954 by Librairie Gallimard

under the title Les Mandarins

First English translation published in Great Britain by Collins 1957

Copyright Librairie Gallimard 954

English translation copyright Collins 1957

Introduction copyright Doris Lessing 1993

A catalogue record for this book

is available from the British Library

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents

portrayed in it are the work of the author's imagination. Any resemblance to actual

persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

ISBN 0 00 720394 2

Set in Sabon

Printed and bound in Great Britain by

Clays Ltd, St Ives plc

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be

reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted,

in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical,

photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior

permission of the publishers.

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

To Nelson Algren

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

by Doris Lessing

Even before The Mandarins arrived in this country it was being discussed with the lubricious excitement used for fashionable gossip. Everyone knew the novel was about the political and sexual lives of Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir and their friends, a glamorous group for several reasons. First, they were associated with the French Resistance, and of all the heroic myths of the Second World War the Resistance was the most potent. Then, they were French, and it is hard now to explain the degree of attractiveness France had for the British after the war. It was only partly that we knew our cooking and our clothes to be inferior, that they had a style and panache we lacked. The British had been locked up in their island for the long years of the war, could not refresh themselves outside it, and France wore the features of some forbidden Paradise. And, too, intellectual communism, intellectuals generally, were glamorous in a way they never have been here, not least because what The Mandarins were debating along the Left Bank were questions about the Soviet Union scarcely acknowledged in socialist circles here, or, if so, only in lowered voices. There was another reason why The Mandarins was expected to read like a primer to better living, and that was the relationship between Sartre and de Beauvoir, presented by them, or at least by Sartre, as exemplary. It was close and matey, like a marriage, but without the legalities and obligations of one, while both partners had absolute freedom to pursue sexual adventures they fancied. This arrangement, needless to say, appealed particularly to men, and innumerable sceptical women were lectured by actual or possible mates on how they should take a lesson from Simone, a woman above the petty jealousies that disfigure our sex. As it turned out, women were right to be sceptical, but there was for us too an attraction in that comradely relationship over there in Les Deux Magots and the Flore, where Jean-Paul and his long-term woman Simone together with all his petites amies, where Simone and her steady, Jean-Paul, and her other little loves, male and female, all forgathered daily to partake of lofty intellectual fare, watched by hundreds of reverential disciples. But it turned out there was nothing of this ideal relationship in the novel, and the Simone figure, Anne, was presented as a dry and lonely woman, in a companionable marriage, resigned to early middle age.

Sartre then stood for an adventurous optimism about science. There was a film about him, showing him stepping out of a helicopter, then the newest of our toys, hailing the brave new world of technology, the key to unlimited progress. We needed this kind of re-evaluation, after watching for the years of the war how war used our inventions and discoveries for destruction.

And then, there was Existentialism. Just as most communists had never read more of Marx than