EDITORS NOTE

From May to July 1948 the journal Les Temps Modernes, directed by Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir, published three extracts from a forthcoming work on the situation of woman, with the general title Woman and Myths. They were part of the third section of the first volume of The Second Sex and dealt with the image that Montherlant, Claudel and Breton gave of women in their novels. Her analysis was harsh, her tone biting, and the often-virulent criticism was not long in coming. Simone de Beauvoir wrote on 3 August to the American writer Nelson Algren, with whom she was involved for a year: [The Second Sex] is a big and long work that will take at least another year. I want it to be really good [...]. I hear it said, and this really pleases me, that the part published in Les Temps Modernes infuriated several men; it is a chapter devoted to the absurd myths that men cherish about women, and to the ridiculous poetry they manufacture about them. The men seem to have been hit where it hurts.

The first volume was finished in autumn, recalled Simone de Beauvoir in Force of Circumstance, and I decided to take it right away to Gallimard. What should I call it? I thought about it for a long time with Sartre [...]. I thought of The Other, The Second: that had already been used. One evening, in my room, we spent hours throwing words around, Sartre, Bost and I. I suggested: The Other Sex. No. Bost proposed: The Second Sex, and upon reflection, it fit perfectly. I feverishly set to work on the second volume.

As of May the following year, Les Temps Modernes published three new extracts from the second volume: Sexual Initiation, The Lesbian and The Mother. The first two are in the part called Formative Years and the third in Situation. Franois Mauriac, a journalist at LeFigaro newspaper, was particularly outraged by Simone de Beauvoirs writing on sexuality and started an inquiry into the so-called message of Saint-Germain-des-Prs and expected young intellectuals and writers to totally disavow the surrealist and existentialist movements whose influence he claimed to see in Simone de Beauvoirs work. Reactions were not long in coming and the Catholic writer, probably to his great surprise, did not find the unanimous condemnation he was expecting. Authors brought quite nuanced answers to the question that rather proved, with all due respect to Mauriac, that an inevitable evolution was occurring in postwar France, an evolution in morals and mentalities and in mens and womens relations.

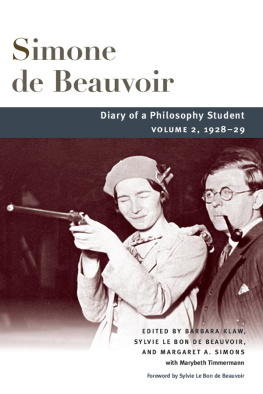

In June 1949 the first volume of Le Deuxime Sexe (The Second Sex), subtitled Les Faits et les mythes (Facts and Myths), was published by Gallimard (with the authors name in black capital letters on an ivory cover, and the title in red capitals). It carried a strip embellished with a picture of Simone de Beauvoir and Jean-Paul Sartre at the Caf Flore, with the caption Woman, this unknown. The book was dedicated to Jacques Bost, and the dedication was followed by quotations from Pythagoras and Poullain de la Barre, one of the first, in the seventeenth century, to have defended the equality of the sexes. Twenty-two thousand copies were sold in the first week, while reviewers went wild.

In August Paris-Match published extracts from the second volume in its issues of 6 and 13 August: A woman calls women to freedom, the weekly proclaims. This volume, subtitled Lived Experience, came out in November. It carried two quotations as epigraphs, one by Kierkegaard and the other by Sartre. One is not born, but rather becomes, woman can be read in the first lines of the first chapter. No biological, psychical or economic destiny defines the figure that the human female takes on in society; it is civilization as a whole that elaborates this intermediary product between the male and the eunuch that is called feminine. From then on, it was no longer a question of simply mentioning facts and analyzing a few forms of literary mythification, but of striking at the heart of the edifice of collective representations. Repeated then thousands of times, in all languages, the phrase served as the keystone of feminist thinking for the second half of the twentieth century, and what it says belongs to a veritable conceptual revolution.

In 1949 Simone de Beauvoir was forty-one years old. One word encapsulates her existence up to that point and for a long time afterward: freedom. In her autobiographical opus in which, starting in the 1960s, she resuscitated the past with rare openness, the notion was felt, as of adolescence, as a profound and irrepressible drive. Superficially, the destiny of a girl of the Parisian bourgeoisie in the 1920s seemed all worked out: marriage and motherhood will raise her to the rank of wife and then mother; society doesnt expect anything else of her. If by chance she is educated, if she likes studying enough to want a profession, shell feel very quickly that there are necessary sacrifices: she will give up her career plans to devote herself entirely to her family. That is what Colette Yvers novels, which Beauvoirs father liked so much, taught; and that is what the adolescent firmly rejected. She will not be a housewife, she will be mistress of her own life. The struggle was first of all on an individual level. Exist for oneself, break with existing patterns, be free to dispose of ones own life. How? By acquiring a financial and intellectual autonomy, by studying to be able to have a real profession. Simone de Beauvoir counted on becoming free through her own capacities, and not without difficulty. In her family, as in thousands of others, everything was a question of powerful prejudices and harsh discussions: the books one could read, the friends one could see, the young men with whom one was allowed to go out, the studies that could be envisaged. The adolescent stood fast (without having total control), decided she would be a teacher (a feminine profession) and then that she would sit for the philosophy