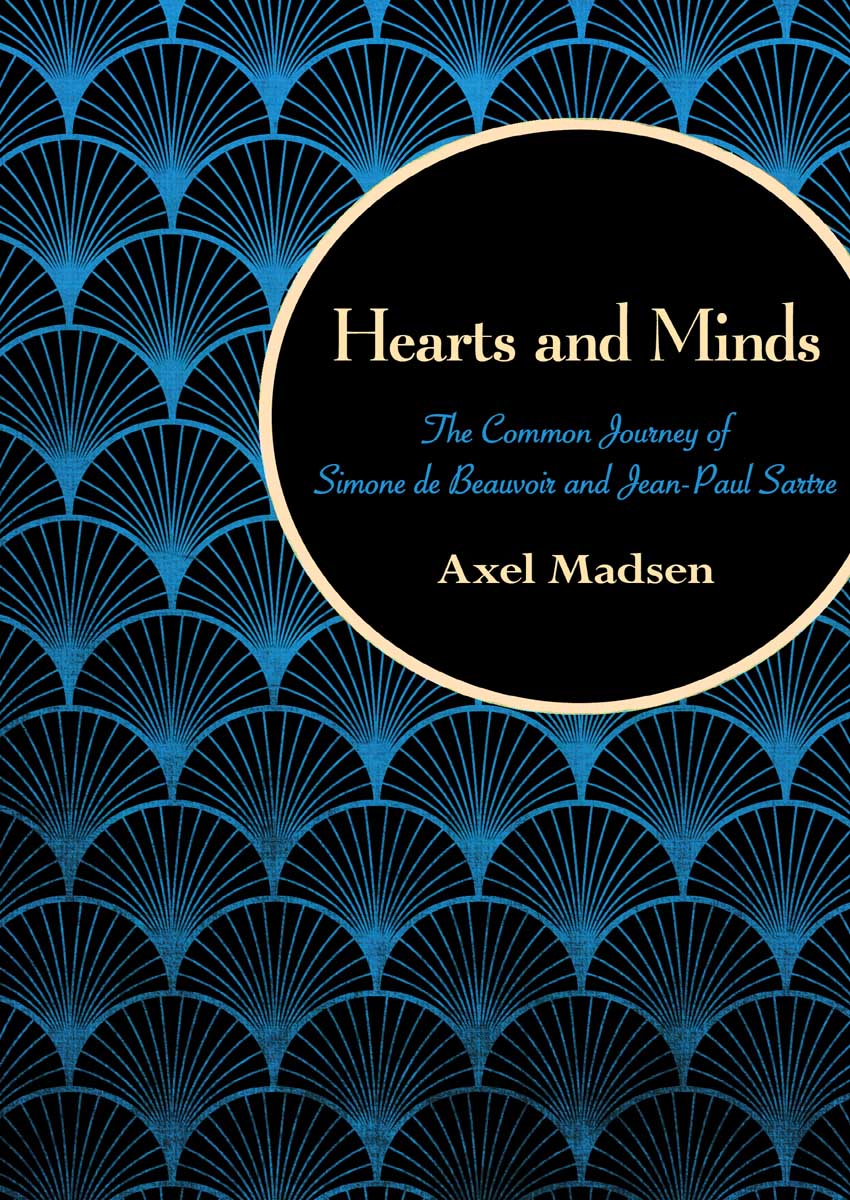

Hearts and Minds

The Common Journey of Simone de Beauvoir and Jean-Paul Sartre

Axel Madsen

CONTENTS

Works

by

Sartre

and

Beauvoir

Bibliography

Chapter 1

Summer of 1929

No books, Jean-Paul Sartre had decreed, just long walks and longer talks, even if the boggy hollows of the Limousin uplands were too much chlorophyll, as he joked. Simone de Beauvoir joined him every morning as soon as she could get away from her family, running across still dewy meadows to reach their secret rendezvous. There was so much to talk aboutthe friends, books, life and, of course, their future. They took long walks, two figures in an August landscape; she tall and gangly; he short and square and with a crossed right eye behind the schoolmaster glasses. He laughed a lot. They were brand-new teachers, the two top graduates of their class. They had worked terribly hard, but still, she said, she was sure her first paycheck would be a practical joke.

All too soon it was time for her return to Meyrignac for lunch while he sat under a hedgerow eating the cheese or gingerbread smuggled out of the Beauvoir kitchen by Simones cousin Madeleine who adored anything romantic. In the afternoon they were together again, picking up the discussions started in Paris before the holidays or in a chestnut grove before lunch. She had told her parents they were working on a book, a critical study of Marxism. Her idea had been to butter them up by pandering to their hatred of communism. All too soon the sun plunged into the hills beyond the Auvezre River, sending her back to Meyrignac and him to the Hotel de la Boule dOr and dinner among the traveling salesmen.

Like him, she was born in Paristhey might have played together in the Luxembourg Gardens, they discovered. Both had spent precocious childhoods in coddled surroundings and both thought a lot of themselves. The difference was the country. Every summer since she had been a little girl she had scratched at earth, played with lumps of clay, polished chestnuts and learned to recognize buttercups, ladybirds, and glowworms at her grandfathers five-hundred-acre estate. Meyrignac, which had been in the family since the 1830s, had a dammed-up stream with waterlilies and goldfish and a tiny island that could be reached via stepping stones. It had fields, cedars, willows, magnolias, shrubberies and thickets. At Meyrignac and at La Grillire, her uncles estate twenty kilometers away, she had always been allowed to run free and to touch everything. Uncle Maurices park was bigger and wilder but also monotonous and it surrounded a sinister turreted chteau that looked much older than it really was. Uncle Maurice, a member of the local gentry, had married Papas sister, Helene.

Jean-Paul had an eccentric grandfather. Charles Schweitzer was a handsome language teacher with a passion for the sublime, who in old age looked so much like God Almighty that repentent parishioners in a dimly lit church once took him for an apparition. Charles spent his life turning little events into great circumstances that his pudgy and cynical wife reduced to insignificance with a raising of her eyebrows. The Schweitzers were Alsatians and Protestants. Charles brother had become a Lutheran minister who in turn had begotten a minister, Albert, who was now a doctor-missionary in darkest Africa. Charles had become a teacher and coauthor of a Deutsches Lesebuch, used in German classes in all schools in France, and the father of two sons and a daughter. The elder son had settled into civil service and the younger had been a teacher of German until he died, still a bachelor, with a revolver under his pillow and twenty pairs of worn-out shoes in his trunks. Anne-Marie Schweitzer was gifted and pretty, but the family thought it distinguished to leave her gifts undeveloped. She had met Jean-Baptiste Sartre at Cherbourg, a young naval officer already wasting away with tropical fever. They had been married two years when he died and Anne-Marie had returned to her parents with her baby. Charles Schweitzer had found his son-in-laws untimely death insolent and blamed his daughter for not having foreseen or forestalled it. He had applied for retirement but without a word of reproach went back to teaching to support Anne-Marie and her infant son. Chilled with gratitude she had given herself unstintingly, keeping house for her parents and becoming an adolescent again, asking for permission to go out.

Maheu was also married. He never brought his wife to the Sorbonne and disappeared into a suburban train every evening. To Beaver, he liked to underline the difference between himself and Sartre and Nizan. He was a sensualist, he said, enjoying works of art, nature and women; they heaped scorn on exalted principles and had to find the reason behind everything. Werent they the ones who had thrown water bombs at the mundane and vaguely Nietzschean elitist students with shouts of Thus pissed Zarathustra!? Nizan, who was always biting his nails and wore steel-rimmed glasses, was up on artistic fashion and introduced the others to James Joyce and the new American novel. He belonged to various literary circles, had joined the Communist Party and lived with his in-laws in a smart apartment where his and Henriettes studio was decorated with a portrait of Lenin, cubist posters and a reproduction of Botticellis Venus. Most important, Nizan had had a book published.

Sartre had been writing since he was tenstories, poems, essays, epigrams, puns, ballads and a noveland he never stopped telling girls he met that they should also write. Only by creating works of the imagination could anyone escape from contingent life, he said. Art and literature were absolutes, which didnt mean he had any intention of becoming a professional man of letters. He detested literary movements and hierarchies and couldnt really reconcile himself to become a career person with faculty colleagues and college presidents.

There were many things Sartre didnt want to become. He would never be a family man, he would never marry, never settle down and never clutter up his life with possessions. He would travel instead and accumulate experiences that would benefit his writing. In theory, Simone admired dangerous living, lost souls and all excesses, but for her graduation had meant liberation, moving away from home. For her, life would begin in October.

She had never felt she was a born writer, but at fifteen, when writing in a girl friends scrapbook about the future, she had scribbled that she wished to become a famous author. At eighteen she had written the first pages of a novelabout an eighteen-year-old girl whose obsessive concern was to defend herself against other peoples inquisitiveness. When they had all crammed together in the Nizans studio, Sartre had made fun of her parochial-school vocabulary, although he, too, admitted he was really seeking salvation in literature.

What Simone liked about Sartre was that he never stopped thinking, never took anything for granted and that on the subject that interested her above all othersherselfhe tried to understand her in the light of her own set of values and attitudes. He told her she should hold on to her personal freedom, should remain curious and open and really do something about wanting to write. Only two and a half years older than she, Sartre impressed her by his maturity. Her cousin Jacques had been her first adolescent crush, Maheu had been the first man to make compliments on her figure. Sartre was the first man who was like her, only much more so, someone who wanted the same things as she, but who had more self-assurance than she could muster.

There were differences of course. Simone thought it was a miracle that she had managed to break free from her narrow upbringing and looked toward the future with excitement; Sartre detested adult life. At twenty-four, he didnt particularly look forward to military service and the necessity of teaching for a living, but all this didnt prevent him from saying that people should create their own lives and that freedom had to be the essence of