Axel Madsen - Malraux: A Biography

Here you can read online Axel Madsen - Malraux: A Biography full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2015, publisher: Open Road Distribution, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Malraux: A Biography

- Author:

- Publisher:Open Road Distribution

- Genre:

- Year:2015

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Malraux: A Biography: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Malraux: A Biography" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Malraux: A Biography — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Malraux: A Biography" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Malraux

A Biography

Axel Madsen

Chapter 1

To see an aquarium, better not be a fish.

Picassos Mask

The last meaningful revolution, you ask me? His gaze is keen and searching. Modern revolutions are either hangovers from 1917 or they are fascist takeovers, but of course the Russian Revolution, the Chinese Revolution require cobblestones to make barricades against cavalry. With the invention of the tank, revolutionary action really becomes obsolete.

Andr Malraux is an elegant and slightly bent septuagenarian of extravagant memory and prodigious knowledge who receives his visitor with formidable verbosity and a choice of Scotch or mint tea. He talks about what Mao Tse-tung told him and what he told Trotsky and Kennedy and about Historys finer ironies. He recalls camels coming down the Pamirs, bellowing through the clouds, and says that listening to Europes great composers in Asia makes him feel that the Wests deepest emotion is nostalgia. He talks about the next wara war for diminishing resourceswhile contrasting his darkening vision with faith in human resilience. He says God is dead, but that what ultimately matters is neither material rewards nor even happiness but spiritual dimension. What makes humanity awesome and culture a great adventure is not our own saying so, but our questioning everything.

His spare strands of hair are dark, his eyes green and his face, with its chiseled furrows and nervous twitches, is dominated by the arch of his brow. He examines his visitors half-finished sentences with intuitive impatience. He has a gift for taking quick and forceful possession of ideas and for formulating them in dazzling propositions. Yet his language is without redundancy or hesitancy. He never seems to feel his way toward ideas, and words flow from him at a rate that is almost the speed of thought. For punctuation, he may lift a long, apostolic forefinger and say, Mais, attention! as if to warn of upcoming illuminations. Objections are taken into account and a partner in conversation may come to feel grateful that doubts are entertained at all. Ideals are not defended with asperity but with common sense and a series of primo, secundo and tertio to keep matters straight until all extensions, consequences and impossibilities of various hypotheses have been disposed of and a cogent conclusion reached. When conversing with Malraux, Andr Gide has said, one doesnt feel very clever.

War puts questions stupidly, peace mysteriously. Our history is not a chronicle of ideologies or political abstractions, but of empires, of powers seeking to control events.

He has always felt the tragic dimension of modern man and his novels are peopled with characters who in violent situations fight to create their own transcendental usefulness. He believes our civilization no longer has a clear idea of man and is therefore bound to change or disappear.

You ask me if the universe has a purpose, if history leads somewhere or whether such questions are senseless. Not senseless, Id say, unintelligible. The Iranians have given the answer in the Koran a modern twist: Does the cricket run over by a truck understand the internal combustion engine? The cricket may think it has been run over by something very big and very nasty, but not how the internal combustion engine works. Nor what the engine thinks, or that it doesnt think at all. Man thinking of himself in biological terms started with Darwin. The idea of a common human fate is very recent, and we dont even know yet whether evolution is divergent or convergent.

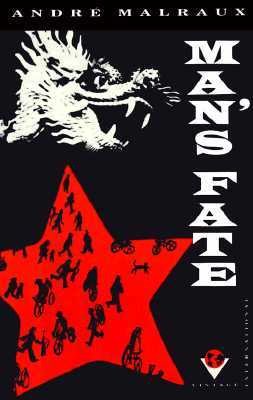

Malrauxs progression has been from high-pitched radicalism to political agnosticism and art as transcendence rather than beauty. His fiction is a tragic universe where individuals are opposed to society but at the same time draw their forces from it, a world where revolutions fail but justice rekindles justice and where to accept the unknown is to be fully human. A revolutionary movement is fraternal not only because it defends the individuals values but because in revolt the individual exceeds himself. In his books, clear-eyed revolutionaries and magnificent losers die so that others may live with dignity. What do you call dignity? It doesnt mean anything, a Kuomintang officer asks the captured Kyo in La Condition humaine, which in English received the title Mans Fate. The opposite of humiliation, the revolutionary answers. Pages later, he realizes that to die for human dignity is to die a little less alone.

Malrauxs last novel appeared in 1943. Since then, he has published over fifteen books, memoirs of his extraordinary life not always written in the first person and volumes about art and the creative process which say that what ennobles Man is what transforms him. Art is a dialogue we have always carried out with the unknown. We have come to distinguish the contours of the unknown through the unconscious, through religion and magic and we may soon begin to understand such totally modern emotions as the feeling that we belong to the future, that our civilization is the sum total of all others.

Five books appeared between 1974 and 1976, all parts of his ongoing life work. La Tte dobsdienne, which became Picassos Mask in English, sees art as its own absolute, freed even of a need to be beauty, and as promise of a universal language that allows modern man to converse across civilizations and time. It is also about Pablo Picasso and the traces the artist leaves behind. Lazare is a meditation undertaken in the limbo of critical illnessMalrauxs own voyage to the edge of death in 1972 when a collapsed peripherical nervous system threatened him with paralysis of the cerebellum and total amnesia. It is also about the realization that the medical technology that saved him had not existed a few years earlier. Together with other, as yet unpublished texts, La Tte dobsdienne and Lazare will form the second volume of the Antimmoiresanti because Malraux wants the ego talking about itself to yield to what is created in life. LIrrel and LIntemporel are the second and third volumes of The Metamorphoses of the Gods. LIrrelin English perhaps not so much the unreal as the non-realsees the Renaissance as the stupendous turning point when artists stopped re-creating the world according to sacred tenets and began re-creating it according to imaginary values. LIntemporelin Malrauxs view neither timelessness nor immortality, but the peculiar time warp that allows a work of art to escape its own eratraces the volte-face of modern painting since Manet with whom Venus ceased to be both naked woman and poetry to become color arranged in certain forms. With these two big, richly illustrated volumes, Malraux has finished The Metamorphoses of the Gods, his reflection on art and its transmutations, started in 1957 as an afterthought to the monumental Voices of Silence, his hymn to art as intelligence imposed on matter.

He receives his visitors at the Vilmorin family chteau in Verrires-le-Buisson on the southern outskirts of Paris where he lives surrounded by the affectionate attention of the sister and family of the last woman in his life. Louise de Vilmorin lies buried somewhere in the park-sized garden under a cherry tree. The cherries will rain down on my tomb and children will feast on them, the novelist wrote in her will. Verrires is less than ten miles from the city limits and only a last few fields from suburban high-risers. The lovers of Verrires, twentieth-century Chateaubriand and Madame Rcamier, found each other late and lived a whimsical if autumnal liaison. De Gaulle didnt exactly approve but when Madame de Vilmorin died, the president sent a rare personal note. A year later, he died.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Malraux: A Biography»

Look at similar books to Malraux: A Biography. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Malraux: A Biography and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.