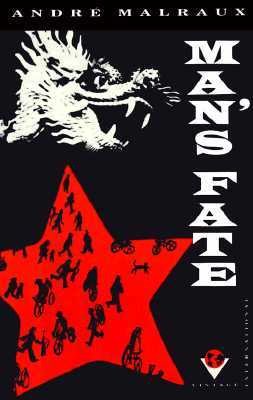

Silk Roads

The Asian Adventures of Clara and Andr Malraux

Axel Madsen

To Arnold Orgolini, a friend who continued to believe.

Contents

Foreword

In the years just after the Great War, adventure in faraway places was the thing for smart young people. Andr Malraux had been spared, not because of luck in the trenches but because the slaughter had stopped at his toes. By 1918 boys a year older were being called up, and when it was all over France had suffered nearly a million and a half killed in action, a third of them young men between eighteen and twenty-eight. Having been born in November 1901 instead of November 1900 made him and many of his contemporaries want to prove themselves by seeking perilous action and bracing ventures. Nor was Clara Goldschmidt much different. When the two of them got married (on a dare and to scandalize their elders) she, too, wanted to show her mettle. To go on a treasure hunt in the jungles of Southeast Asia was a sporting way of showing one belonged to the new Reckless Twenties.

This uncommon couple found more than they bargained for in colonial French Indochina, and their story is a tale of romance, crime, and political awakening. Claras nonchalant Jewishness and an upbringing that embraced antagonistic nationalities made her sympathetic to the grievances of Vietnamese, Cambodians, and Laotians. Because Andr was all French and because he modishly dismissed all political action, his reaction to the clammy paternalism of Indochinas French rulers was one of principle. Clara found racial injustice immoral; he scorned a society based on conformity, exclusion, and the surrender of principles.

Together and separately, Clara and Andr lived to see the yearnings, aspirations and defiance they encountered in Cambodia and Vietnam defeat the will of Western powers. They lived to see the follies of French colonialism, of one people ruling another, inflame American passions and pain. A year after President Lyndon Johnson threw Americas might into the rice paddies of Vietnam, Andrs visit to a forbidden China in the throes of its cultural revolution was also a covert mission to sound out Mao Zedong on the possibility of rapprochement with the Americans. In 1972, on the eve of President Richard Nixons historic trip to China, Andr was flown to Washington to brief the President.

In Paris three years later, the author speculated with Andr on the grand and collective Whither humanity? Helicopters were plucking Americans from the roof of the Saigon embassy while, at the end of his long and tumultuous life, Andr Malraux told his visitor that the major facts of our time are not events, not even such admittedly shattering occurrences as the advent of the nuclear age, but the shifts in the way we think, in the relentless way we question who we are.

We are, Andr Malraux believed, at the end of the empires because the sense of manifest destiny is disappearing everywhere, even in communism. It has never happened before that the worlds most powerful nation has no sense of what it wants. Yet the United States no longer has any manifest destiny, nor does Russia. The Chinese dont have it either. Domestically, yes; the national will power is very real. But when they say they want to change Tanzania, theyre talking propaganda. What will happen after the empires fall is hard to foretell, because profound change is, by definition, subterranean and because we have a tendency to take our problems for examples. The question is not one of morality but of destiny; were not looking for a new Moses to give us new laws, were trying to find out what we can be. He found it stupefying that the era that discovered nuclear physics and unlocked the genetic code is satisfied with conceiving man somewhere between Marx and Freud.

A few years later, an octogenarian Clara thought back to the time Andr and she were together, when she hated her own semifailures and resented the way Andr began to write her out of the novels that detailed their Asian adventures. In the name of their total commitment she had cut herself off from her family and accepted misery. He had felt no need to excuse himself. He not only insisted he had every right to transpose personal experiences into fiction but also believed that, rearranged in this fashion, events appeared more plausible. I was the repudiated wife of the great man and after that, through the peculiar independence that World War II gave me, I recovered my contours and stopped being someone you could see through. Vietnam, she would say, both wrecked and enriched us. With the weapons that were only his, Andr would try to dominate the world that, until then, had resisted him. Through his writing he would impose his vision. Our Indochina escapade, exploits, and enterprises would result in books that gave the adventures meaning. She too became a writer, first of fiction inspired by the Indochina ventures and, late in life, of a multivolume autobiography that earned her wide recognition.

If there is a challenge to writing about famous people it is to sketch the portraits while faces and traits are still fleeting and motives still tentative, to catch them before they know who they are, before the features are chiseled in accomplishments, fame, and guile. It is before we are somebody that we are interesting.

Here is Andr Malraux before he could talk about what Mao Zedong told him and what he told Trotsky and Kennedy; before the musings about historys finer ironies; before evocative memories of camels coming down the Pamirs, bellowing through the clouds; before his intuition that what makes humanity awesome and culture a great epic is not our own saying so but our questioning everything. Here is Clara before her difficult journey through life, a young woman of privilege and shining intelligence who would come to believe that her true dramaand that of many womenwas that to be fulfilled she needed the contact, stimulation, and embrace of a masculine mind stronger than hers.

This book is one of those looking-glass stories that both recreate an exotic world and illuminate the way we change. It is not American flaws and failure that are exposed here, but another peoples mistakes and failure to capture hearts and minds. Yet, unlike the missed opportunities of the British in India, the French failures in Indochina would come to haunt the American conscience. This book is both a prophetic journey and a backward glance, an evocation of a vanished world and a reflection on its consequences. It is a story of love, of emotional liabilities, and of commitments to a cause. Above all, it is the story of youth, a time before fame, when all was possible.

PART ONE

Chapter 1

Lorelei

They stood leaning on the port-side railing, a smart young couple in wispy summer clothes. She told him theyd hear the legendary echo when they got right under the cliff. He wondered whether the people living along the banks were as much influenced by the river as they were separated by it.

To fellow passengers they were a somewhat incongruous pair: he a lanky, nervously elegant youth, she a vivacious brunette barely tall enough to reach his shoulder. He was a pale and intense twenty-two-year-old with a flair for mocking gestures and a surly hauteur people found attractive because he looked even younger than he was. She was a diminutive woman of twenty-five whose plainness was forgotten in her elan, her sea-green eyes, her resonant laughter, and the movements of her butterfly hands.

The rhetorical question is whether there is such a thing as a Rhenish culture, he said.

Lorelei hurled herself into the river in despair over a faithless lover.

Do you think well