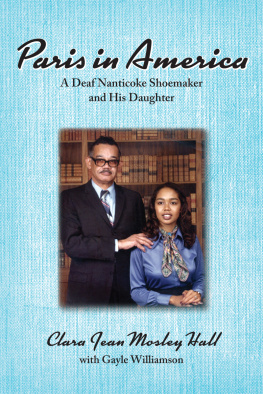

Clara Jean Mosley Hall - Paris in America: A Deaf Nanticoke Shoemaker and His Daughter

Here you can read online Clara Jean Mosley Hall - Paris in America: A Deaf Nanticoke Shoemaker and His Daughter full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: Washington, DC, year: 2018, publisher: Gallaudet University Press, genre: Home and family. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Paris in America: A Deaf Nanticoke Shoemaker and His Daughter

- Author:

- Publisher:Gallaudet University Press

- Genre:

- Year:2018

- City:Washington, DC

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Paris in America: A Deaf Nanticoke Shoemaker and His Daughter: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Paris in America: A Deaf Nanticoke Shoemaker and His Daughter" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Paris in America: A Deaf Nanticoke Shoemaker and His Daughter — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Paris in America: A Deaf Nanticoke Shoemaker and His Daughter" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Paris in America

A Deaf Nanticoke

Shoemaker and His Daughter

CLARA JEAN MOSLEY HALL

with

Gayle Williamson

Washington, D.C.

Gallaudet University Press

Washington, DC 20002

http://gupress.gallaudet.edu

2018 by Gallaudet University.

All rights reserved. Published 2018

Printed in the United States of America

ISBN: 978-1-944838-35-5

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Hall, Clara Jean Mosley, 1953- author. | Williamson, Gayle, 1966-author.

Title: Paris in America: a deaf Nanticoke shoemaker and his daughter / Clara Jean Mosley Hall with Gayle Williamson.

Description: Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press, [2018] | Includes bibliographic references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018032026 | ISBN 9781944838355 (pbk.) | ISBN 9781944838362 (e-book)

Subjects: LCSH: Hall, Clara Jean Mosley, 1953- | Nanticoke Indians--Delaware--Biography. | Children of deaf parents--Delaware--Biography. | African Americans--Delaware--Biography.

Classification: LCC E99.N14 H35 2018 | DDC 975.1004/97--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018032026

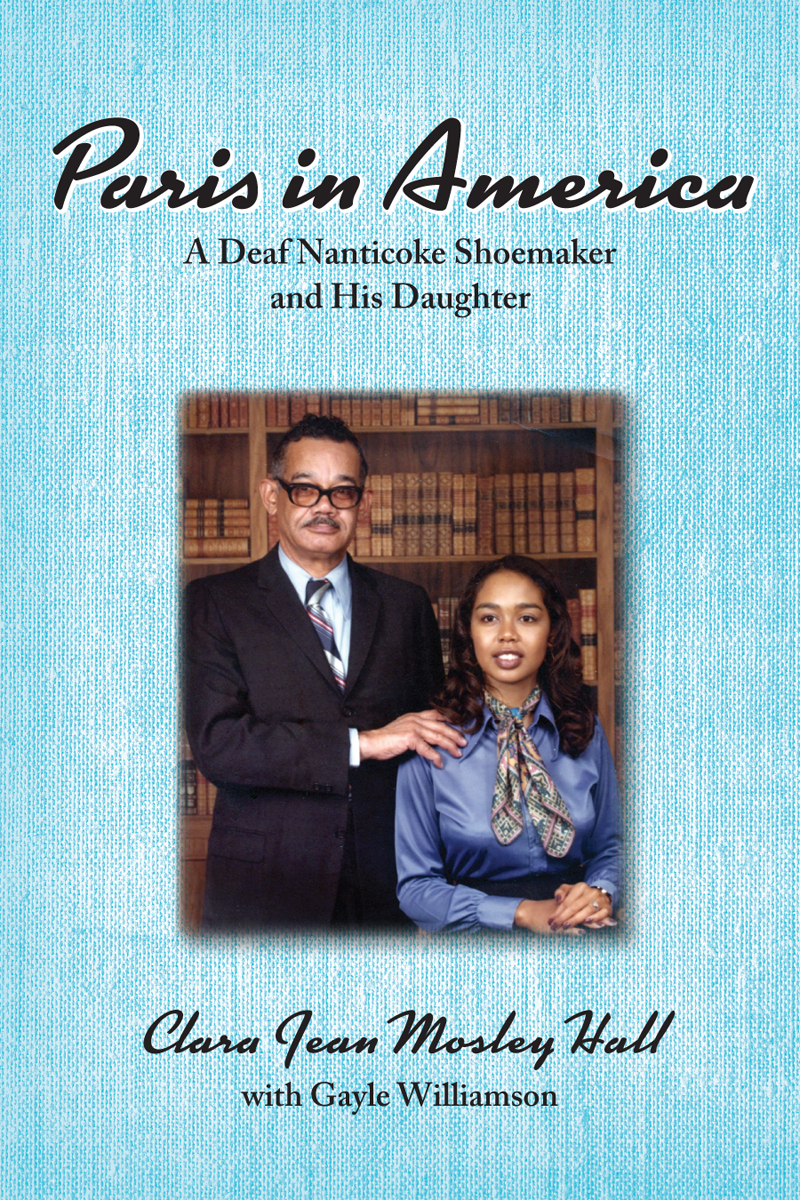

Cover photo: Courtesy of Jeanie Mosley Hall.

For more information and photos, go to nativeamericansofdelawarestate.com/Mitsawokett Photos/MoseleyJamesParis.htm.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

For my husband, Howard (Seeker of Truth), and daughters,

Ilea (Healing Hands) and Karelle (Spirit Dancing); the reason

for everything I do. I love you with every ounce of my being.

To the memory of my extraordinary father, James Paris Mosley,

who showed me the unwavering power of love.

Clink, Clink, Clink:

Interpreting Sounds Not So Silent and Other Things

AUTHORS NOTE

There is no label such as disabled

or handicapped in Native languages.

Linda J. Carroll, President

Intertribal Deaf Council 19982002

MY PURPOSE IN WRITING THIS MEMOIR IS TO DOCUMENT family history and culture: to provide a historical anchor that includes the cultures of Native Americans, African Americans, and Deaf Americans as they intersect with each other and with the broader population. By illuminating the capabilities of people who are deaf through the example of my father, James Paris Mosley, I also hope to be a support to you, the reader, in following your passion toward your dreams and goals no matter the obstacles you may face.

One of the foundations of Native American cultures is the circle. The medicine wheel is a circle of colors representing the people of the world, energy, and spiritual components, as well as the directions of the earth: north (white: representing air, animals, receiving energy, and mental capacity); east (yellow: representing fire or the sun, determines energy, spirituality, illumination, and enlightenment); south (red: representing water, plants, giving of energy, emotionality, innocence, and trust); west (black: representing the earth and physical aspects, holds energy, insight, and introspection). These are all connected to learning, balance, self, harmony, and beauty. The circle holds the world in balance. No one is above or below the circle; thus, everyone has been created equally.

If one aspect of the circle is missing, disturbed, or has been broken, problems will occur and there is discord. That is why historically in Native American cultures, people who were differently abled were not stigmatized or perceived and labeled as disabled or handicapped. There were no words to indicate such. All people, hearing or deaf, were considered gifts from the Great Spirit and a part of the circle. In fact, early Native Americans believed that the stronger spirits chose to inhabit a body with, for example, deafness or blindness, and they received honor for their choice. Before the arrival of Europeans, disease and deafness were not common among Native populations, which may also explain why there are no words to represent this condition in Native languages.

High value is placed on making wise and balanced choices in relationships and interactions with one another because they affect everyone. Our individual actions have an impact on others positively or negatively. This concept is expressed in the words of Chief Seattle who was a Suquamish Tribal Chief known for accommodating the White settlers. He said, Man does not weave this web of life. He is merely a strand of it. Whatever he does to the web, he does to himself. Therefore, in Native cultures, being deaf is merely a description, such as being short or thin. No stigma is attached to the explanation. These ideas represent long-established beliefs within Native nations. Unfortunately, not everyone within Native cultures has adhered to the traditional ways and beliefs. There are elders, however, who have stepped up to the challenge of bringing the old ways of thinking back to the present. They are preserving traditions, customs, and the way of life that revere people who are deaf because they represent the strongest, most spiritually advanced among us.

Native American deaf people from various tribes have had difficulty accessing their Native culture because of the language barrier between hearing and deaf indigenous people. This is true of any dual culture or multicultural deaf person (see, for example, Hairston and Smith, 1983; Anderson and Miller, 2004; and McCaskill et al., 2011). The National Multicultural Interpreter Project in El Paso, Texas, and the Southwest Multicultural Interpreters Network in New Mexico are helping to alleviate issues of erroneous interpreting for multicultural deaf individuals by mainstream interpreters who are not familiar with indigenous cultural differences. It is imperative that interpreters be well-versed in all languages and cultures they represent so that they can accurately convey both meaning and cultural aspects of the languages. Damara Goff Paris, one of the editors of Step into the Circle, the first collection of stories from Native Americans who are deaf, discusses how they come to terms with their dual identity. One writer summed it up by simply stating that he refers to himself as a Deaf American Indian when he is among people in the Deaf community where deafness and American Sign Language (ASL) form a common bond, and as an American Indian Deaf man when he is with the Native American community where Native culture is dominant.

Native Americans still experience a lack of services as well as isolation in the labor force. Certain Native populations, such as Alaska Natives, Cherokee, and Creek, have a higher rate of hearing loss due to otitis media (middle ear infections). This loss, which can lead to speech, language, and educational difficulties, can be partially attributed to the lack of access to adequate medical care, upper respiratory infections, and exposure to tobacco smoke. Some Deaf Natives have an additional barrier to deal withthe lack of access to clear and equal communicationand this has prevented them from learning about their heritage because they do not have easy access to the Elders and other spiritual leaders who could pass along cultural ways.

Historically, deaf children, like Native American children, were sent far away from their homes to schools where their heritage was not taught. Deaf Native children in American deaf schools learned ASL, which is different from American Indian Sign Language (AISL) and may not be known by hearing members of the Native Community. Karen Billie Johnson, a Din Navajo, remembers being sent to the New Mexico School for the Deaf when she was six years old. It was the first time that she had experienced electricity and running water. While at the school, she learned ASL and the importance of pointing to identify people or objects in a conversation or dialogue. When she went back home, she learned very quickly that pointing was considered an insulting gesture in her Native culture. Needless to say, Karen had to learn how to behave appropriately in both cultures (Anderson and Miller, 2004, 30). Today, only a few Native Americans know the sign language used by Native Americans long ago, and they are just now trying to teach those who never learned.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Paris in America: A Deaf Nanticoke Shoemaker and His Daughter»

Look at similar books to Paris in America: A Deaf Nanticoke Shoemaker and His Daughter. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Paris in America: A Deaf Nanticoke Shoemaker and His Daughter and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.