Contents

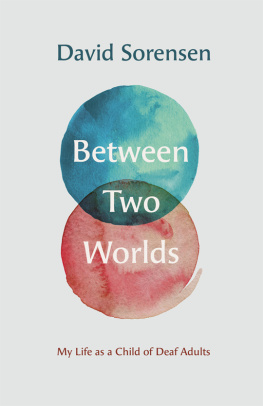

Between Two Worlds

Gallaudet University Press

Washington, DC 20002

http://gupress.gallaudet.edu

2019 by Gallaudet University

All rights reserved. Published 2019

Printed in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Sorensen, David, 1950

Title: Between two worlds : my life as a child of deaf adults / David Sorensen.

Description: Washington, DC : Gallaudet University, [2019]

Identifiers: LCCN 2018045408| ISBN 9781944838539 (pbk.: alk. paper)

| ISBN 9781944838546 (e-book)

Subjects: LCSH: Sorensen, David, 1950- | Children of deaf parents--Biography.

| Deaf--Family relationships--United States--Biography.

Classification: LCC HQ759.912 .S67 2019 | DDC 305.9/081--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018045408

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

Contents

Introduction

A Correspondence from My Homeland

O FTEN THROUGHOUT my adult years, having grown up in a deaf family, I divorced myself, by choice or by happenstance, from the Deaf community altogether. Sometimes, so much of my life has been like living in another country, my family on the opposite shore. It is only now, after thirty-nine years and many life experiences later, that I realize I have come full circle back into the country of Deaf people. I am a hearing child of deaf adults. We are called Codas, and we are our own breed.

Being a Coda within Deaf culture is distinguished by certain roles and characteristics. As the firstborn, my responsibility at an early age was that of an interpreter for my parents, which later was deferred to my younger sister. I was asked my opinion on certain adult decisions such as interpreting medical information. As I became older, I was a confidant to other deaf adults throughout their decision-making processes. Being born within a deaf family had its privileges, namely that I was accepted into the inner circle as a trusted member of the Deaf community even though I was hearing. However, there were limitations there, too. For example, sometimes I was not included, such as at a basketball tournament that permitted only deaf players.

Relations between my father and me and how we communicated (minimally), as well as his discipline style (inconsistent, at times with his belt and other times yelling), were scary and intimidating for a young kid. My attention-seeking and wanting my fathers approval or attention, by any meansstealing, lying, through sports, or interpretingwas a dynamic in our relationship. On the other hand, my mothers attempts to discipline were the opposite of my father. She was much more reserved and passive, and she would resort to wait until your father comes home. The relationship between my parents and the Mormon Church were big influences on the family dynamic, influences that sometimes broke us apartthings that I understand better now. There were times I felt my parents were vacating their roles as parents to attend to the needs of others, to the church, and to my grandmother. My relationship with my sister Christy was difficult at times. She was much younger, and our views differ greatly even today about our deaf parents and our experiences.

But here is what I learned in my home country, through my deaf family: How to teach American Sign Language, which I did at two community colleges in Arizona and Nevada. How to work in group homes for deaf individuals through the community outreach program for the Deaf in Tucson. How to become a teaching assistant at the Oregon School for the Deaf in Salem. How to get myself into graduate school at the University of Arizona. How to work as an educational assistant at the Arizona School for the Deaf and Blind in Tucson. How to counsel deaf individuals in Tucson. How to advocate for deaf services in the Nevada legislature. How to develop a deaf residential treatment program at Desert Hills in Albuquerque. How to work with private nonprofit agencies in developing two group homes for the deaf people, one in San Diego, another in Albuquerque, which was La Familia, which I led as clinical director. How to start my own private practice Southwest Services for the Deaf, in Albuquerque. How to be a strong voice on issues related to deaf people.

By profession, I am a mental health therapist who is fluent in American Sign Language (ASL) and understands Deaf culture. This fluency and cultural understanding allowed me to be trusted, accepted, and valued when I returned to my homeland, the country of Deaf people.

I was born and raised in a deaf family in a time when Deaf culture existed, but was not quite identified yet. Yes, there were schools for deaf people; yes, there was sign language; yes, there were Deaf clubs; and yes, there were national Deaf organizations. However, sign language back then was considered a system of gestures and manual communication, not a bona fide language. There was no Deaf culture; there were only a handful of agencies working with deaf populations. Interpreters? What interpreters? Interpreting wasnt a profession; it was a way to help deaf people. My familys interpreters were my sister, my fellow Coda comrades, and me. Even the term Coda was not invented; we simply said, mOther-father deaf. Contacting someone? Go next door to the neighbor familys house and use their phone or jump into your car, if you could afford it, and head over to your friend Bobs or Garys twenty to thirty miles away for a chat. If they werent home, tough luck; leave a note.

It was not until the late 1950s or early 1960s when the first teletypewriter, or telecommunications device for the deaf (TTY/TDD), was widely used for communication, as long as you could find another deaf individual or family that had a TTY. In the 1960s and 1970s, sign language was finally recognized and verified as a distinct language; it was not a code or version of English or other spoken languages. Community agencies serving deaf people started springing up everywhere. Research took place at various colleges and universities studying sign language, including the renowned Salk Institute. The Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf, a national certifying agency, was established in 1964. The term Deaf culture finally appeared in the 1970s and is now a household term.

Today, the United States has more than 125 interpreter training programs, along with a national interpreting certification. State commissions and agencies are committed to working with deaf people. About 175 residential schools, charter schools, and school programs for the deaf exist in the United States. Individual communication devices and technologies have gone from the TTY to relay services to videophones and even mobile devices, so that now deaf people can independently make doctor appointments, talk with their attorneys, schedule time to meet with their banks, set up appointments for haircuts, or order pizza. Laws have lessened, somewhat, discrimination at work and created better access for deaf people to programs and services. Most television programs are captioned. And now consider this... deaf people now have their own recognized language American Sign Language, which was the third most-used language in this country, according to a 2006 article in Sign Language Studies by Ross E. Mitchell of the Gallaudet Research Institute and colleagues. Deaf people have come a long way since the 1950s.