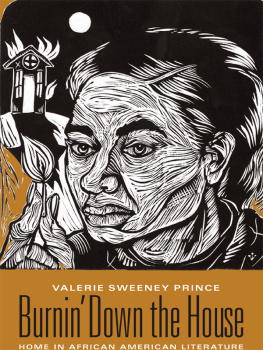

Burnin Down the House

VALERIE SWEENEY PRINCE

Burnin Down the House

Home in African American Literature

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS / NEW YORK

Columbia University Press wishes to express its appreciation for a donation toward the cost of publishing this book, given to Hampton University in memory of Frank Carmines.

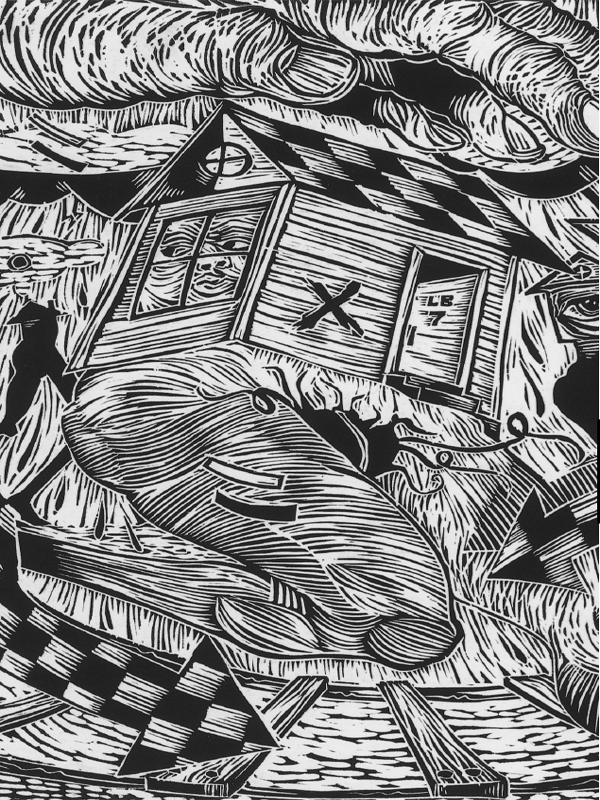

Grateful acknowledgment is given to Steve A. Prince for use of the following:

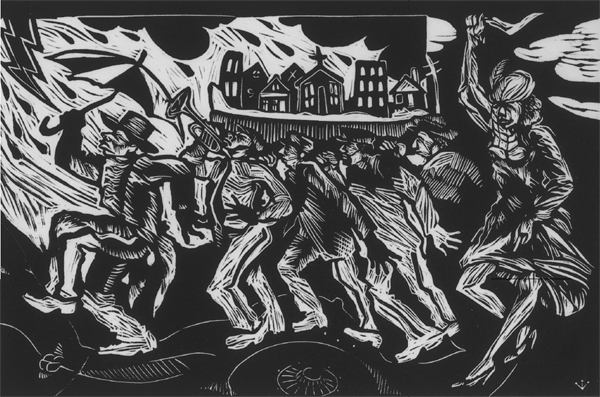

When I Think of Home (linoleum print, 9 x 12, 1998) from the Home Series [frontispiece]

Urban Dirge (linoleum print, 9.5 x 14, 2003) from the Home Series

Ghetto Squares (linoleum print, 8 x 15, 2003) from the Home Series

Migratory Tracks (linoleum print, 8 x 10, 2003) from the Home Series

Pot to Piss In (linoleum print, 5.5 x 10, 2003) from the Home Series

Ill Lay My Head on Some Lonesome Track (linoleum print, 7.5 x 14, 2003) from the Home Series

Sugarman Blues (linoleum print, 7 x 10 2003) from the Home Series

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2005 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-50879-7

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Prince, Valerie Sweeney.

Burnin down the house: home in African American literature / Valerie Sweeney Prince.

p. cm.

ISBN 0231134401 (alk. paper)ISBN 031134411X (pbk. : alk. paper)

PS374.N4P75 2004

813.0093552dc22 2004049444

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

To Amee, who said, Go!

Contents

How does any work get done except by the labor of many hands? This particular project has been in the making for more years than I generally acknowledge, but it initially crystallized in a single word during graduate school. The word was, of course, home. I returned home by the sea to finish this book and was received into the welcoming arms of so many peopleMargaret Simmons, Barbara Whitehead, Lois Benjamin, William R. Harvey, Joann Haysbert, John Alewynse, Joyce Jarrett, Mamie Locke, April Burris, Bradford Grant, Regina Blair, Jacqueline Regina Blackwell, and Amee F. Carmineswho stood tirelessly urging me forward. Amee, in particular, has been my friend and ally, reading and critiquing when no one else was around. My cousin Lois read an early draft and helped me find my own voice. I write of home because I have a family, not untroubled, not without conflict, not romanticized; I come from somewhere.

Over the years of work on this project, many students have inspired me and helped me to better articulate exactly what I mean. They have endured my obsession with the themes of space and place and home. But those at home have endured the worst of it. My parents, Robert and Lurlene Sweeney, are battle-worn soldiers who stood at the ready for me, always doing whatever was required. My children, Imani and Elijah, have learned patience, independence, and strength, having been born to a mother who simply must write. And my beloved husband, Steve, who can make art out of anything, makes it possible for me to do this work day to day. I thank him for the designs that grace the cover and head each chapter. He continues to be my inspiration.

My sister, Maria, her husband, Neil Osborne, and their daughter, Drexel, opened their home to me and endured my endless chatter without complaint on my trips to Cambridge during the last phase of this project. Their generosity and hospitality were invaluable to its timely completion. The editors at Columbia University Press, Jennifer Crewe and Leslie Kriesel, provided invaluable assistance in refining the finished product.

Carlo Rotella also motivated me. As I watched him speak at the MLA convention in San Francisco in 1998, he was a stranger, but during a time when I needed encouragement, his professionalism and intelligence made me hold to my convictions. His words about working until he finds just the right way to express what he means were not lost on me. One can be a hero without even trying sometimes.

Without the inspiration given by the Holy Spirit to lay everything down and to pick up only those things that Christ allows, I would never have been able to bear all the costs of seeing this project through. Most of all, I thank God for being my home in this world.

I would not change a moment of this walk. Although the work is secular, the journey has been sacred.

When I think of home, I think of a place Where theres love overflowing.

I wish I was home, I wish I was back there With the things I been knowing.

Charlie Smalls, Home

BONO: Searching out the New Land. Thats what the old folks used to call it. See a fellow moving around from place to place woman to woman called it searching out the New Land. Aint you never heard of nobody having the walking blues?

August Wilson, Fences

Not a house in the country aint packed to its rafters with some dead Negros grief.

Toni Morrison, Beloved

The search for justice, opportunity, and liberty that characterized the twentieth century for African Americans can be described as a quest for home. During the early part of the century, America witnessed the largest mass migration in history. African Americans left the South looking for opportunity promised by the industrial North. The North did offer relief from the despotism of Jim Crow, which was ruthlessly enforced by mob violence, but poverty and racism also awaited the migrants in northern cities. Overcrowded ghettos began to fester with the stench of unfulfilled promises and the rotting corpses of failed dreams lying unburied and unmourned upon hard ground. By the mid-twentieth century, Claude Brown had joined a chorus of talented black writers including Arna Bontemps, Countee Cullen, Claude McKay, Sterling Brown, Lorraine Hansberry, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Ann Petry, and James Baldwin, who were already voicing their frustrations. The dream that Harlem Renaissance author Langston Hughes wrote about had indeed been deferred. Anger arose as a wall built in defense of this sacred place of home. Black writers had invested too much to let the ideal die so unceremoniously. Passion for home ran like lifeblood through the African American psyche.

A look back upon the century of African American literature shows that home is ubiquitous and nowhere at the same time. Perhaps that is why authors express the longing for home utilizing the language and the sentiment of the blues. The blues form arose near the turn of the twentieth century out of the privation experienced by African Americans. It gives voice to the frustrations suffered by the masses of black people living in a culture of white supremacy and presents a unique worldview. The blues introduces a logic drawn from African American sensibility that makes the notion of home seem possible in a chaotic world.