INTRODUCTION

I. THE WORK

There is a set-phrase in Chinese referring to the phenomenon of Li Po: Winds of the immortals, bones of the Tao. He is called the Banished Immortal, an exiled spirit moving through this world with an unearthly ease and freedom from attachment. But at the same time, he belongs to earth in the most profound way, for he is also free of attachments to self, and that allows the self to blend easily into a weave of identification with the earth and its process of change: the earth perpetually moving beyond itself as the ten thousand things unfold spontaneously, each according to its own nature.

In Chinese, this unfolding is tzu-jan: literally self-so or being such of itself, hence natural or spontaneous. Li Pos work is suffused with the wonder of being part of this process, but at the same time, he enacts it, makes it visible in the self-dramatized spontaneity of his life. To live as part of the earths process of change is to live ones most authentic self: rather than acting with self-conscious intention, one acts with selfless spontaneity. This spontaneity is wu-wei (literally: doing nothing), and it is an important part of Taoist and Chan (Zen) practice, the way to experience ones life as an organic part of tzu-jan. Educated Chinese had always been imbued with Taoist philosophy, and Chan had become very influential among the intellectuals of Li Pos time, many of whom associated with Chan monks and spent time in Chan monasteries. Wu-wei was therefore a widely-held ideal, appearing most famously in wild-grass calligraphy (begun by Chang Hs and Huai Su, friends of Li Po who would get drunk and, in a sudden flurry, create a flowing landscape of virtually indecipherable characters), in the antics of Chan masters, and in Li Po himself.

But for Li Po, it seems not so much a spiritual practice as the inborn form of his life, much of which was spent wandering. As this was primarily wandering on whim rather than traveling of necessity, it gives his life the very shape of spontaneity: sailing downriver hundreds of miles in a day or settling in one place for a year. Li Pos spontaneity also takes the form of wild drinking and a gleeful disdain for decorum and authority, as in the story where he fails to pay the proper respects when being introduced to a governor and, upon being reprimanded, quips: Wine makes its own manners. Li Pos poetry was itself often intended to shock his readers, and he was considered outlandish by the decorous literary society of his time. But it was in another aspect of his writing that Li Po embodies the principle of wu-wei in a more fundamental way: the headlong movement of the poem and its gestures. This movement is a natural result of the spontaneous composition process which is a major part of the Li Po legend. The story recurs in many forms, perhaps most famously in Tu Fus Song of the Eight Immortals in Wine:

For Li Po, its a hundred poems per gallon of wine,

then sleep in the winehouses of Chang-an markets.

The most essential quality of Li Pos work is the way in which wu-wei spontaneity gives shape to his experience of the natural world. He is primarily engaged by the natural world in its wild, rather than domestic forms. Not only does the wild evoke wonder, it is also where the spontaneous energy of tzu-jan is clearly visible, energy with which Li Po identified. And the spontaneous movement of a Li Po poem literally enacts this identification, this belonging to earth in the fundamental sense of belonging to its processes.

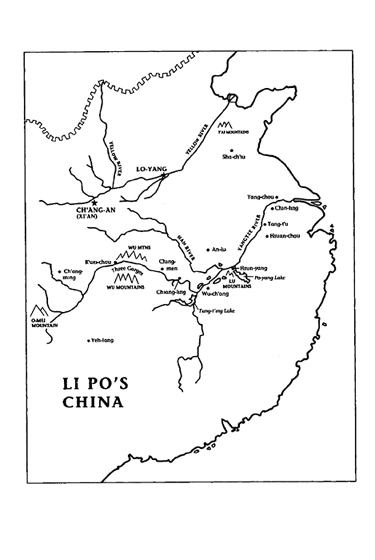

Li Po wrote during the High Tang period (A.D. 712-760) when Chinese poetry blossomed into its first full splendor, and he is one of the High Tangs three preeminent poets, Wang Wei and Tu Fu being the other two. A major catalyst in the High Tang revolution was admiration for a poet who had been neglected since his death three hundred years earlier: Tao Chien (365-427), the poet of fields and gardens. Wang Wei, Li Po, and Tu Fu are all direct heirs to Tao Chiens resolute individuality and authentic human voice. But Li Po is no less heir to Hsieh Ling-yn (385-433), the poet of wild mountains and rivers. Mountains were not merely natural, but sacred objects. Quite literally sites where the powers of heaven met those of earth, they were inhabited and energized by those powers. Rivers formed part of a single cosmic watershed. Beginning in western mountains where the Star River (our Milky Way) descends to earth, they flow east toward the sea, and there ascend to become again the earth-cradling Star River. And together mountains and rivers literally means landscape, wild landscape as a truly numinous phenomenon.

The moon, though, absorbed the Banished Immortal utterly. Appearing in over a third of his poems, it is a beacon from his homeland. Its difficult for us now to imagine what the moon was for Tang intellectuals, but it was not in any sense the celestial body that we know. In a universe animated by the interaction of yin (female) and yang (male) energies, the moon was literally yin visible. Indeed, it was the very germ or source of yin, and the sun was its yang counterpart. Like all other natural phenomena, a persons spirit was thought to be made up of these two aspects. It took the form of two distinct spirits: the yin spirit, which was called po and remained earthbound at death, and the yang spirit, which was called hun and drifted away into the heavens at death. The moon, too, was known as po or yin-po. Hence, the moon was the heavenly incarnation of, was indeed the embryonic essence of that mysterious energy we call the spirit (yin spirit, with the sun being the source of yang spirit). This is the conceptual context within which Li Pos poems operate, the cultures account of the moons mystery. But rather than account for it, the poems themselves evoke it directly, evoke it and yet leave it as it is, even now: an enduring mystery.

With the moon, inevitably, comes wine. Drinking plays an important part in the lives of most Chinese poets, acting as a form of enlightenment comparable to Chan practice. But only Tao Chien is as closely identified with the sage in the cup as Li Po. Usually in Chinese poetry, the practice of wine involves drinking just enough so the ego fades and perception is clarified. Tao Chien called this state idleness (hsien): wu-wei as stillness. But although Li Po certainly cultivates such stillness, he usually ends up thoroughly drunk, a state in which he is released fully into his most authentic and enlightened self: wu-wei as spontaneity.

During Chinas Tang Dynasty, a man named Li Po is born in the year 701, at the beginning of the great cultural flowering known as the High Tang. He wanders. The moon beckons from his homeland, dances with his shadow. The river flows on the borders of heaven. He meets Tu Fu in a country wineshop, and they share a few days. Armies burn fields and cities. The Tang smolders, a fitful ruin. In 762, Li Pos wandering ends south of the Yangtze River, at someone elses house, when he falls into a river and drowns trying to embrace the moon. The phenomenon of Li Po moves perpetually beyond the everyday facts which make up a life. He belongs at once to the realm of immortals and to the earths process of change, its spontaneous movement beyond itself. But his most enduring work remains grounded in the everyday experience we all share. He wrote 1200 years ago, half a world away, but in his poems we see our world transformed by winds of the immortals, bones of the Tao.