Contents

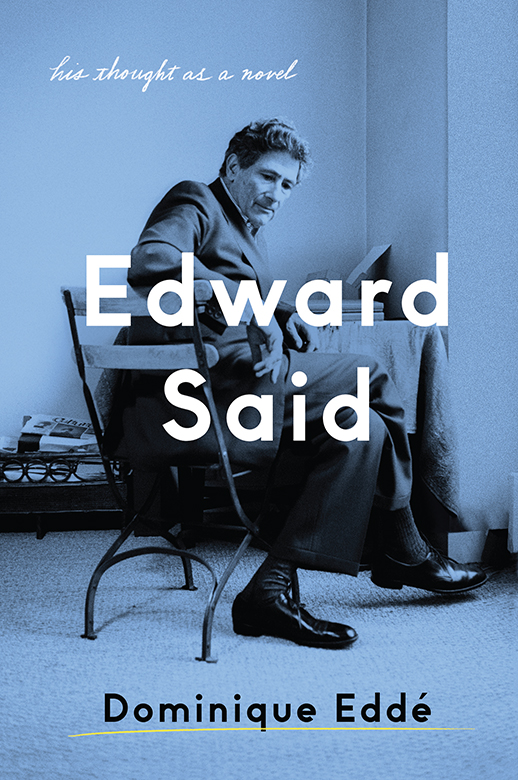

Edward

Said

His Thought as a Novel

Dominique Edd

Translated by Trista Selous and Ros Schwartz

This work is published with support from the French

Ministry of Culture / Centre national du livre

First published in English by Verso Books 2019

First published as Edward Said: Le roman de sa pense

Editions La Fabrique 2017

Translation Trista Selous and Ros Schwartz 2019

Quotations from the works of Edward Said reproduced

with permission from the Wylie Agency

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-78873-411-0

ISBN-13: 978-1-78873-412-7 (UK EBK)

ISBN-13: 978-1-78873-413-4 (US EBK)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

Typeset in Garamond by Biblichor Ltd, Edinburgh

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY

his thought as a novel

Edward

Said

Dominique Edd

CONTENTS

Edward Said was both an author and an extraordinary orator, who took as much pleasure as he gave from the act of turning his thought into a living thing into theatre. Standing before a packed audience, speaking low and fast, his eyes always watchful, sometimes amused, sometimes serious often both at once looking over round glasses set on the end of his nose, occasionally straightening his torso with a quick movement of his neck or arms, his hands accompanying his phrases with long, mobile fingers, he could turn the examination of a dry quotation from Auerbach or the latest agreement between the Israelis and Palestinians into a moment of pleasure. As a speaker he was an artist. He made skilful use of irony, gravity, paradox, erudition and repetition. He trusted his intelligence to hold the attention of his audience and his charm to win them over; he used his persuasive power to soothe his own deep, albeit invisible, anxiety. When moved by anger, he could sometimes wrestle it into icy irony, sometimes not. At these times, his sarcasm would break out, revealing the full extent of his hurt. Were it not for the help of music, the war machine against which he battled the combined political and military power of Israel and America would probably have exhausted his strength long before he developed leukaemia. He had the great courage to place his knowledge and energy at the service of a cause that could never be won in a single lifetime, at any price. Fighting doggedly in a western world traumatised by guilt at having allowed the genocide of the Jews to happen, while having redeemed itself on the cheap at the cost of denial and blindness in relation to the Palestinians, Said managed to maintain his positions without ever ceding an inch of his territory to the anti-Semitism he abhorred to the same degree.

His thought exposes the hasty reader to misunderstanding, because it moves in two directions at once. In counterpoint. The way you play the piano. The right hand is always at work on a construction that never stays still, where conclusions are rarer than they seem and anyway less crucial than the effort made by the left hand to reveal them. There are several tones of voice in Saids work one that is masterful and controlled, another that is irritated and passionate. And a great silence. This silence builds like a secret between him and himself, between Edward, the rebellious heir to an imperial history, and Said, the Palestinian Arab determined to be heard. As a result, there are two kinds of silence in his work. One is maintained by the domination weighing down on the oppressed, which he must break at any price; the other is the silence that allows reason to catch its breath, to turn against itself, which he must keep alight like a smouldering fire. The first is an enemy, the second an ally. Rereading his work in the light of these twin demands makes it much easier to understand. At the same time, Saids phrasing is that of a music lover. Like his friend Daniel Barenboim teaching Arab and Israeli musicians in Weimar, he knew that music must have a good reason to break the silence. And so must writing. But, in the domain of words, the good reason is never as clear or as audible as it is in music. Concluding his text on punctuation, Theodor Adorno, an author to whom Said refers throughout his work, approached the same issue in a different way: In every punctuation mark thoughtfully avoided, writing pays homage to the sound it suppresses.

A critic, writes Said in his first book, Beginnings, is a wanderer, going from place to place for his material, but remaining a man essentially between homes.as the word negritude has become inseparable from Aim Csaire, so the word orientalism now belongs to Said. Having become an obligatory reference in that field, Said then applied his method to contemporary events. Day after day, the abscess of the Palestinian issue fuelled his anger and vigilance, transforming him into a brilliant critic of injustice. He became the most fearsome intellectual opponent of IsraeliAmerican policy rooted in the omnipotence of one people over another. This policy, whose every annexation, confiscation and media lie he highlighted and deconstructed, one by one, did not prevent him from simultaneously emphasising the poverty and corruption of the Palestinian authorities. Nor did it prevent him from locating Zionism within the history of anti-Semitism and genocide he used the word holocaust thus distinguishing it from any old manifestation of colonialism. However, it did prevent him sometimes at least from exposing his ideas to lights that might have enabled a deeper, more complex examination. At such moments, the energy he expended on unmasking and disarming his enemy weakened the force of his critique, turning it into a weapon of riposte and strike. So, Covering Islam, written immediately after the success of Orientalism, is a book as courageous as it is incomplete, spread too thin on the one hand, reductive on the other. It avoids difficult questions which Said would later explore more deeply. These notably include the Quranic foundations of political Islam, the real danger from the lure of Islamism in Arab countries and the need to find a path separating the temporal from the spiritual. The Politics of Dispossession, a collection of writings covering a quarter century from 1968 to 1993, reflects the tireless work of adaptation, adjustment, continuity and correction that he carried out in support of his causes through thought that was always evolving. On this level and on this subject, he was one of the few if not the only one to keep going over the long term with so much rigour, impact and flexibility.

The constant loss of territory, both physical and political, inflicted on the Palestinian people is perhaps not unconnected to the weakening of Saids defences and the emergence in 1991 of his incurable leukaemia, which he kept at bay for twelve years. During those years his work did not change direction, but it did imperceptibly change colour. It aged in the best sense. It paled before the limitations of the project that impelled it. It did not desert its combat zones, but it gave music and the interpretation of the past, including Saids own, a central place that was in part released from any duty to convince. At this time, Said came up against the hard core of thought, which in itself resists the very possibility of solution.