Stepping on the Cracks

Mary Downing Hahn

CLARION BOOKS NEW YORK

Clarion Books

a Houghton Mifflin Company imprint

215 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10003

Text copyright 1991 by Mary Downing Hahn

All rights reserved.

For information about permission to reproduce

selections from this book, write to Permissions,

Houghton Mifflin Company,

215 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10003

Printed in the USA

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Hahn, Mary Downing.

Stepping on the cracks / by Mary Downing Hahn,

p. cm.

Summary: In 1944, while her brother is overseas fighting in World

War II, eleven-year-old Margaret gets a new view of the school bully

Gordy when she finds him hiding his own brother, an army deserter,

and decides to help him.

ISBN 0-395-58507-4

[1. World War, 19391945United StatesFiction. 2. Bullies

Fiction.] I. Title.

PZ7.H1256St 1991 91-7706

[Fic]dc20 CIP AC

QUM 20 19 18 17

This book is dedicated to the Downing family:Especially to the memory of

my father, Kenneth Ernest Downing (190463),and my uncles:Dudley Downing, who was killed in Belgium in 1944 and

awarded the Distinguished Service

Cross for exceptional heroism in combat,andWilliam Alexander Downing, who survived the

Battle of the Bulge in the Ardennes forest.

One afternoon in August, Elizabeth and I were sprawled on my front porch playing an endless game of Monopoly (or Monotony, as Elizabeth called it).

"Your turn," I announced. I'd just passed the bank and picked up two hundred dollars to add to my pile of paper money. For once, I was definitely winning.

When she drew a card that told her to go to jail, Elizabeth threw it down. She was already broke and in debt to me because I owned Atlantic Place and her man kept landing on it. Every time that happened, she had to hand me five hundred dollars rent.

Elizabeth scowled at her little pile of money and ran a hand through her blonde hair, putting a few more tangles in it. Then she poked the Monopoly board with one bare foot, just hard enough to slide the expensive hotels and cottages off my property. Our little men rolled across the porch, and some of the paper money fluttered away.

"Let's go somewhere before I keel over and die of boredom," Elizabeth said.

Ignoring her, I crawled around, gathering up the playing pieces. Unlike Elizabeth, I was perfectly content to spend the rest of the day where we were. The heat had melted my bones away, and I felt as limp as a rag doll. "It's too hot," I muttered, "to do anything."

But Elizabeth wasn't listening. Climbing to the porch railing, she grinned down at me. "Dare me to jump?"

Before I could say yes or no, Elizabeth hollered "Geronimo!" Arching her body, she flew through the air like a circus acrobat and landed gracefully on the grass. "Come on, Margaret," she shouted.

Not wanting to be a sissy baby, I held my breath, leapt off the railing, and hit the ground so hard I knocked the scab off my skinned knee. As I spit on my finger to wipe the blood away, Elizabeth hopped down the sidewalk.

"Step on a crack," she yelled, "break Hitler's back! Step on a crack, break Hitler's back!"

Despite the heat, I stamped along behind Elizabeth. Under my bare feet, I saw Hitler's face on the cementhis beady eyes, his mustache, his mean little slit of a mouth. I shouted and pounded him into the pavement, and every time I said his name it was like swearing. It was Hitler's fault my brother Jimmy was in the army, Hitler's fault Mother cried when she thought I wouldn't hear, Hitler's fault Daddy never laughed or told jokes, Hitler's fault, Hitler's fault, Hitler's most horrible fault. I hated him and his Nazis with a passion so strong and deep it scared me.

Behind me, the screen door opened, and Mother called, "Margaret, how often do I have to tell you not to jump like that?" She frowned at me from the porch. "You won't be happy till you ruin your insides, will you?"

Elizabeth grinned at Mother, her eyes squinted against the sun. "Hi, Mrs. Baker," she said.

Mother looked at Elizabeth, but she didn't return her smile. "What was all that shouting?" she asked. "You two were making enough noise to wake the dead."

"It's a game I thought up," Elizabeth said. "Step on a crack," she yelled, jumping hard on the sidewalk to demonstrate. "Break Hitler's back!"

"When I was your age, we said, 'Step on a crack, break your mother's back,'" Mother told her. "We tried hard not to step on the cracks."

"That was before Hitler," Elizabeth said. "The world was different then."

Mother leaned against the door frame, her arms folded across her chest, and sighed. "Yes," she said, agreeing for once with Elizabeth. "I guess it was."

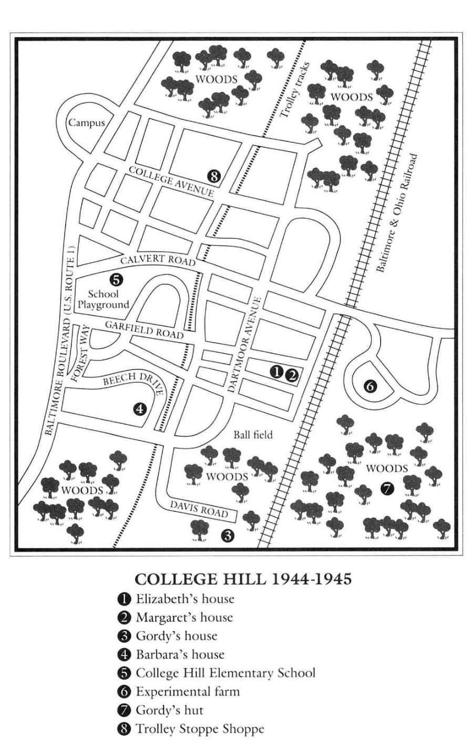

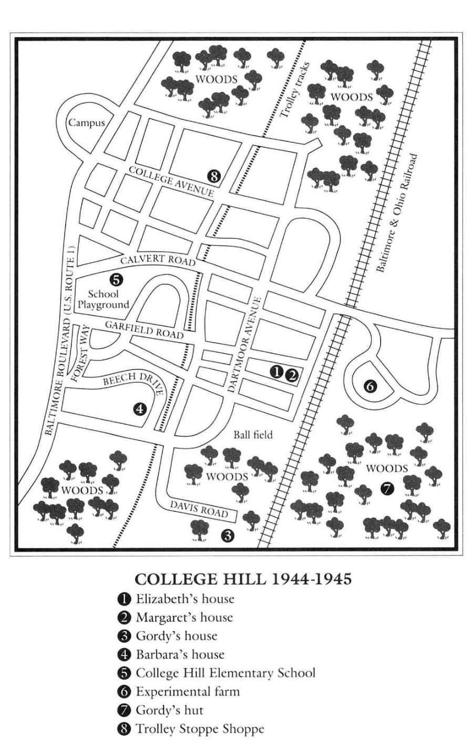

For a moment or two, no one said anything. I saw Mother glance at the blue star hanging in our living room window, and I knew what she was thinking. That star meant Jimmy was overseas fighting a war Hitler started. There was a star in Elizabeth's window, too, because her brother Joe was in the Navy. That summer, there were stars in lots of windows in College Hill, and not all of them were blue. Some, like the one across the street in the Bedfords' window, were gold. The Bedfords' son Harold had been killed in Italy last summer. That was what gold meant.

In the silence, I heard a surge of organ music from our radio. It was time for "The Romance of Helen Trent," one of Mother's favorite soap operas. As she opened the screen door to go inside, Mother paused and looked at Elizabeth. "Where are you two going this afternoon?" she asked.

"Bike riding," Elizabeth said, as if I'd already agreed.

"Don't you dare take Margaret down that hill on Beech Drive," Mother said. "You almost killed yourselves last time."

But she was speaking to the air. Elizabeth had already darted through a gap in the hedge between our houses. In a few seconds she was back with her brother Joe's bike, an old Schwinn. The crossbar was so high Elizabeth could barely straddle it, but she rode it anyway.

Taking my seat on the carrier over the rear wheel, I held on to Elizabeth's waist as she pushed off across the grass. Wobbling till she picked up speed, she pedaled along Garfield Road toward Dartmoor Avenue.

The hot sunlight poured down through the green leaves, dappling the dirt road with a lacy pattern of shadows, and the Schwinn's big balloon tires bounced over the ruts. Mrs. Bedford waved to us from her front porch, Mrs. Porter smiled at us from her side yard, where she was hanging her laundry out to dry, and old Mr. Zimmerman nodded to us from the corner. His little dog, Major, barked and wagged his tail. On a cooler day, he might have chased us.

Through the open windows of every house, we heard snatches of radio shows. The voice of Helen Trent and the happy song advertising Rinso laundry soap followed us down the shady street. College Hill was so peaceful, it was easy to forget the war. In fact, Helen Trent's love life seemed more real than the battles our parents talked about. Although it was 1944, and World War II had been going on for over two and a half years, nothing had happened to change our lives. Except for Jimmy's absence and a lot of shortages, everything was the way it had always been.

With me clinging behind her, Elizabeth crossed the trolley tracks and pedaled past the school, sleeping like a brick giant in the summer sunlight. Soon enough its green doors would open wide and swallow us up, but for now we were safe. Three more weeks of freedom before we faced sixth grade and the dreaded Mrs. Wagner.

Elizabeth turned a corner, and we glided down Forest Way toward Beech Drive. The road here was paved, and Elizabeth pedaled faster, zooming past big brick houses with mossy slate roofs. The bike tires made a hissing sound on the gritty surface of the macadam, and a dog barked at us from behind a picket fence. Otherwise, it was very quiet.

Next page