Professor John C. Wright, University of Kansas, Lawrence, for hisadditional information on noncontingent reward experiments;

Dr. Roger S. Fouts, University of Oklahoma, Norman, for his permission torefer to a forthcoming publication;

the Honorable Ewen E. S. Montagu, CBE, QC, DL, London, for his kind help inchecking on my presentation of Operation Mincemeat;

Dr. Bernard M. Oliver, Vice President, Research and Development,Hewlett-Packard Company, Palo Alto, for his extensive advice on problems ofextraterrestrial communication and his permission to reproduce the codingand decoding of a sample message.

The illustrations are by courtesy of Ann A. Wood.

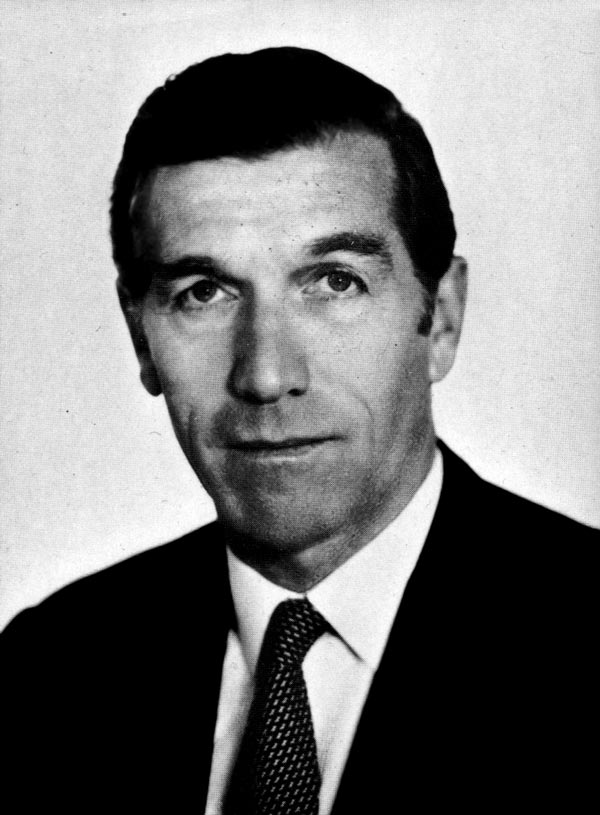

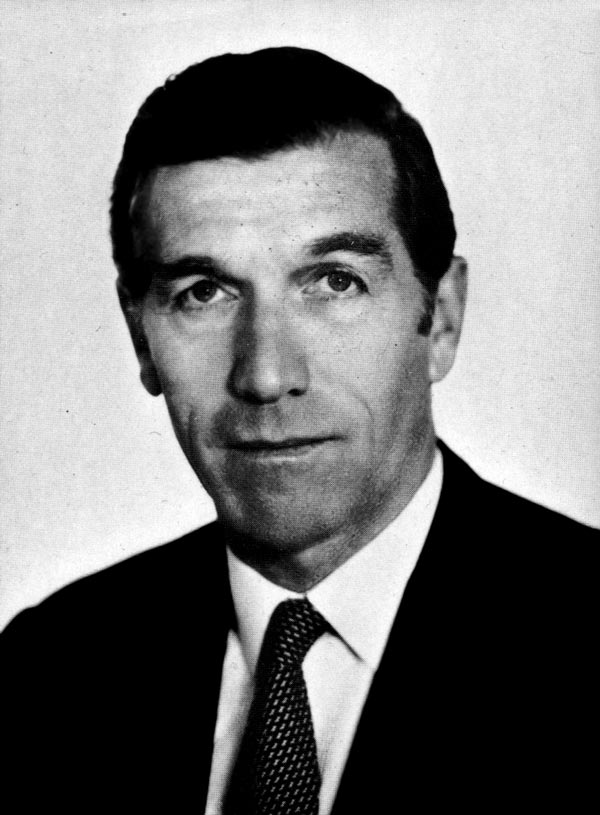

About the Author

Paul Watzlawick , research associate at theMental Research Institute in Palo Alto and clinical assistantprofessor in the Department of Psychiatry, Stanford University, wasborn in Austria, received his Ph.D. in philosophy and modernlanguages from C Foscari University, Venice, Italy, and studiedpsychotherapy at the C. G. Jung Institute in Zurich. He has beenprofessor of psychotherapy at the University of El Salvador, CentralAmerica, a research associate at Temple University Medical Center inPhiladelphia and guest lecturer at many universities and traininginstitutes in the United States, Canada, Europe and Latin America.He is principal author of Pragmatics of Human Communication and Change.

The Trials

of Translation

... let us go down and there confound their language, that they may notunderstand one anothers speech.

Genesis 11:7

All living things depend on adequate information about their environment inorder to survive; in fact, the great mathematician Norbert Wiener oncesuggested that the world may be viewed as a myriad of To Whom It MayConcern messages. The exchange of these messages is what we callcommunication. And when one of the messages is garbled, leaving therecipient in a state of uncertainty, the result is confusion, whichproduces emotions ranging all the way from mild bewilderment to acuteanxiety, depending upon the circumstances. Naturally, when it comes tohuman relations and human interaction, it is especially important tomaximize understanding and minimize confusion. To repeat here an oftenquoted remark by flora: To understand himself, man needs to be understoodby another. To be understood by another, he needs to understand the other[].

Confusion is not usually dealt with as a subject in its own right,especially by students of communication. It is something bad, to be got ridof. But because it is, in a sense, a mirror image of good communication,it can teach us quite a bit about our successes as well as our failures inreaching one another.

Translation from one language to another offers an unusually fertile fieldfor confusion. This extends far beyond plain translation mistakes andsimply bad translations. Much more interesting is the confusion caused bythe different meanings of identical or similar words. Burro, forexample, means butter in Italian and ass in Spanish, and this isresponsible for a number of weird misunderstandingsat least in the punchlines of Hispano-Italian jokes. Chiavari (with the accent on the firsta) is a beautiful resort on the Italian Riviera; chiavare(accented on the second a) is Italian vernacular for love-making.Needless to say, this provides the pointe for a number of somewhatraunchy jokes, all involving tourists who cannot pronounce Italian.Somewhat more serious and less forgivable is the amazingly frequentconfusion of words like the French actuel (the equivalent of theSpanish actual, Italian attuale, German aktuell,etc.), which sounds the same as the English actual (in its sense ofreal or factual) but means present, at this time and even up todate. The same is true of the French eventuellement (Spanish andItalian eventualmente and German eventuell), which hasnothing to do with the English eventually (in its meaning offinally or in the end) but means possibly, perhaps. Considerablymore serious is the frequent mistake committed by translators with thenumber word billion, which in the United States and France means athousand millions (109) but in England and most continentalEuropean countries it means a million millions (1012). There theU.S. billion is called miliardo, Milliarde, etc. The readerwill appreciate that confusion between butter and an ass is of minorconsequence, but the difference between 109 and 1012can mean disaster if hidden in, say, a textbook on nuclear physics.

This confusion about meanings, incidentally, is not limited to humans, asthe book of Genesis implies. Bees, we know from the pioneeringinvestigations of Nobel Prizewinning scientist Karl von Frisch, havecomplex and efficient dance languages, which differ from one species toanother. Since the species cannot interbreed, no language confusion canarise between them. There is, however, a startling exception, which vonFrisch discovered several years ago, involving the Austrian and Italianbees []. They are members of the same speciesand can therefore interbreed, but while they speak the same language, theyuse different dialects in which certain messages have a differentmeaning. When a bee has found a source of food, she returns to the hive andthere performs a peculiar dance which not only alerts the others to herdiscovery but also tells them the quality and location. Von Frisch foundthat there are three dances involved:

1. If a nectar source is quite near the hive, the bee performs a rounddance, consisting in alternating circles to the right and left.

2. If the source is at an intermediate distance, the bee goes into asickle dance, so called because it resembles a flattened figure 8bent into a semicircle, which looks like a sickle. The opening of thesickle points in the direction of the food, and as always in bee dances,the speed of the dance indicates the quality of the nectar.

3. If the source is farther away, the bee attracts the attention of herhive-mates by a wagging dance, moving for a few centimeters in astraight line toward the target, and then returning to the starting pointand repeating the movement. While moving in the direction of the source,the bee wags her abdomen.

The Italian bee uses the wagging dance for distances of more than fortymeters, but for the Austrian bee this dance means a much longer distance.Thus an Austrian bee, acting on the information supplied by an Italianhive-mate, will search for the food too far away. Conversely, an Italianbee will not fly far enough when alerted to food by the wagging of anAustrian colleague.

Bee languages are innate, not learned. When von Frisch producedAustro-Italian hybrids, he found that sixteen of them had body markingsvery much like their Italian parent but spoke Austrian in that they usedthe sickle dance to indicate intermediate distances 65 out of 66 times.Fifteen hybrids that looked like their Austrian parent used the round dance47 out of 49 times when they meant the same distance. In other words, theyspoke Italian.

What is most significant about this example is that we humans run intoprecisely the same kind of confusion when we use body language, which isinherited through tradition and which we are almost totally unaware ofunless we see a member of a different culture use it differently, in a waythat seems to us odd or wrong. Members of any given society share myriadsof behavior patterns that were programmed into them as a result ofgrowing up in that particular culture, subculture and family tradition, andsome of these patterns may not have the same connotations to an outsider.The ethnologists tell us that there are literally hundreds of ways of, forinstance, greeting another person or expressing joy or grief in differentcultures. It is one of the basic laws of communication that all behavior inthe presence of another person has message value, in the sense that itdefines and modifies the relationship between these people. All behaviorsays something; for example, total silence or lack of reaction clearlyimplies, I dont want to have anything to do with you. And since this isso, it is easy to see how much room there is for confusion and conflict.