Printed in the United States of America

First published as a Norton paperback 2011

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact W. W. Norton Special Sales at or 800-233-4830

Manufacturing by Quad Graphics Fairfield

Production manager: Leeann Graham

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

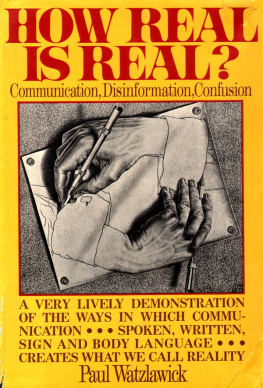

Watzlawick, Paul, 19212007.

Pragmatics of human communication : a study of interactional patterns, pathologies, and paradoxes / Paul Watzlawick, Janet Beavin Bavelas [and] Don D. Jackson ; foreword to the paperback edition by Bill OHanlon.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-393-70707-6 (pbk.)

ISBN 978-0-393-70722-9 (e-book)

1. Communication. I. Bavelas, Janet Beavin, 1940 II. Jackson, Don D. (Don De Avila), 19201968. III. Title.

BF637.C45W3 2011

153.6dc22 2010042214

ISBN: 978-0-393-70707-6 (pbk.)

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd., Castle House, 75/76 Wells Street, London W1T 3QT

To Gregory Bateson,

Friend and Mentor

Foreword to the Paperback Edition by Bill OHanlon

P aul Watzlawick was born in Villach, Austria in 1921, the son of a bank director. He traveled far, spoke several languages fluently, and changed the field of psychotherapy. He passed away in March of 2007.

I first encountered the ideas and the work of Dr. Watzlawick while taking a family therapy course as an undergraduate student at Arizona State University. The instructor, Lorna Molinaire, used the structure of The Pragmatics of Human Communication as her outline for the first semester of a yearlong course. It was my first introduction to a different way of seeing the problems people bring to therapy. And it helped warp me for life.

Although Paul Watzlawick, a psychologist, was schooled in an individual approach to psychotherapy (he was trained as a Jungian), he found his way to a new view. And he was an integral part of bringing this then-radical view into the mainstream of psychotherapy practice.

Taken by his unique point of view and curious for more information, I stumbled on a hidden gem in the audiotape section of my universitys library and spent hours listening to a tape by Watzlawick on human communication (An Anthology of Human Communication: Text and Tape). In it, he told a charming story about a time when he showed up at a psychiatrists office. He wanted to discuss the role communication played in the development of schizophrenia with this particular psychiatrist, who specialized in treating the disorder. But due to Watzlawicks Austrian accent and the fact the his name was not on the psychiatrists appointment book, a simple misunderstanding occurred that showed a lot about communication and its role in problem development.

When Paul announced himself in a rather formal way to the secretary, he said simply, I am Watzlawick. She suspected he was a new psychiatric patient showing up for an appointment at the wrong time, and she interpreted his introduction as, I am not Slavic. To which she replied, I never said you were. At which point, slightly puzzled and a little irritated, he insisted, but I am. Several subsequent exchanges compounded the misunderstanding until they began to yell at each other. At this point, the psychiatrist, hearing the angry exchanges from within his office, poked his head out and said, What the devil is going on out here? Paul, why are you yelling at my secretary, and why are you yelling at Dr. Watzlawick? he asked his secretary. The misunderstanding was quickly cleared up at that point, but Watzlawick used the story to illustrate the importance of context, interaction, and human communication in problem development.

Dr. Watzlawick and I had our differences: he once scolded me when we were on a panel together for suggesting that clients had solutions to their problems that can be evoked for rapid change. If patients had solutions, they wouldnt come to therapy. Its because their solutions arent working or are the very cause of their problems that they seek our help, he thundered at me. I respectfully disagreed and today the solution-based approach to change is well established and accepted. Most clinicians would accept that clients often have their own solutions to problems that can help resolve them.

But Watzlawicks view reflected the hard-won knowledge that attempted solutions often made a problem worse or keep it in place. This is a view that I have found profoundly useful over the years with many clients, so I can appreciate his loyalty to it.

Hopefully the new edition of the book will find new readers and bring back previous ones to revisit this revolutionary tome.

The Pragmatics of Human Communication fired the first shot to signal a revolution in the field of psychotherapy. Previously, most therapeutic approaches were focused on the individual (monadic, as this book terms it). The approach introduced here, very radical for its time but not so now, since its message has been absorbed into the mainstream, was that behavior and symptoms in the area of mental health cannot be understood properly without considering context, interaction, and communication.

The ideas in this volume derived in large part from the discussions that took place in Gregory Batesons research group analyzing communication patterns. This group included (at times) Jay Haley, John Weakland, Paul Watzlawick, psychiatrist Don Jackson, and communication analyst Janet Beavin (Jackson and Beavin went on to become the coauthors of this book). The idea that problems were not always the result of deep underlying psychological issues, but instead arose from interactional and communication patterns, emerged from those fertile discussions and found its way here.

This book, along with Haleys Strategic Psychotherapy, also published in the 1960s, signaled the shift from an individual to an interpersonal lens for viewing therapy problems and solutions (notice the language shifts from symptoms to problems, indicating a move away from the pathological and psychodynamic framework). The ecology movement was just beginning at the time Pragmatics first came out, but that sense that we are all embedded in contexts was not at all intuitive for many people.

The structure of this book reflects Watzlawicks rather formal bentit is divided into numbered sections. It is also a bit heady and a bit philosophical, but for those who stuck with it, the underlying message was powerful and transformative. It still is. While Watzlawick went on to write more books on his own and with others, Pragmatics firmly established him as a seminal thinker, theorist, and force in the field of psychotherapy.

Read it over; digest it carefully. There is a powerful message here that can shift the way all clinicians think about people and problems.

Introduction

T his book deals with the pragmatic (behavioral) effects of human communication, with special attention to behavior disorders. At a time when not even the grammatical and syntactic codes of verbal communication have been formalized and there is increasing skepticism about the possibility of casting the semantics of human communication into a comprehensive framework, any attempt at systematizing its pragmatics must seem to be evidence of ignorance or of presumption. If, at the present state of knowledge, there does not even exist an adequate explanation for the acquisition of natural language, how much more remote is the hope of abstracting the formal relations between communication and behavior?