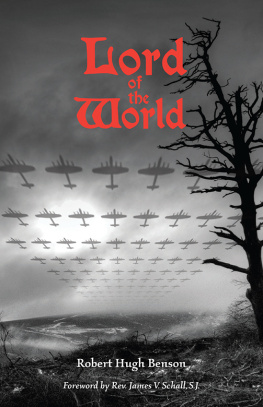

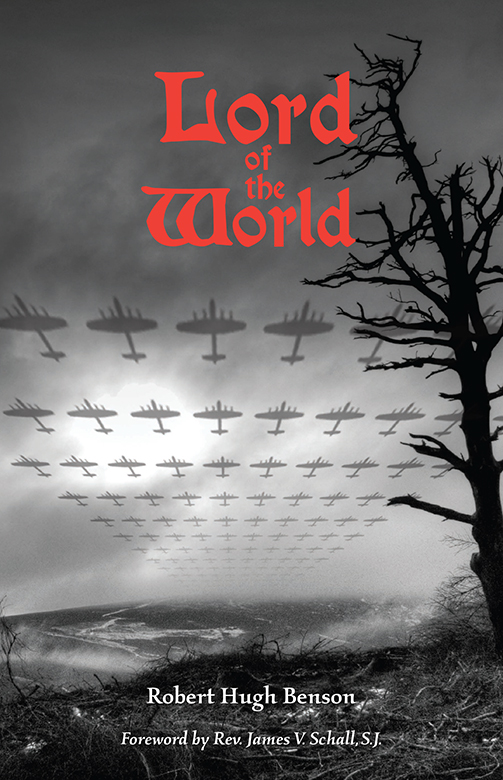

Retypeset by TAN Books in 2016. The type in this book is the property of TAN Books and may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without written permission from the publisher.

Foreword by James V. Schall, S.J., copyright 2016 TAN Books.

I n 2001 (surely not on 9/11!), St. Augustines Press published a new edition of Robert Hugh Bensons 1907 novel, The Lord of the World. I had never read it. A friend of mine in Vermont urged me to read it, and so I did. And, now, I have the pleasure to introduce a new generation of readers to this wonderful book.

The late Ralph McInerny, in a brief introduction to that edition, writes: The novel wonderfully conveys the flatness and boredom of a world without God. Boredom becomes a condition for recognizing our need for something more than thisa few more decades of life and then a total void.

This novel is remarkably similar in theme to Benedicts encyclical Spe Salvi, one of the very great encyclicals. That is, the novel is about the futility of a this-worldly utopia with the instruments of death (abortion, euthanasia) and endless life (prolongation of life, cloning) that are designed to make it come about. Indeed, in a lecture he gave at the Catholic University in Milan on February 6, 1992, Joseph Ratzinger cited The Lord of the World and the deadly Universalist, inner-world atmosphere it depicted.

My father had this Benson novel around the house when I was a boy in Iowa. I remember reading it. What I remember most about it was how frightening it was to me with its vivid end-of-the world description. Indeed, I have often said that this novel and C. S. Lewis That Hideous Strength are the most frightening books that I have ever read. Now, no longer a youth and then some, when I ask myself why this fright, it is because both books make the this-worldly triumph of evil so plausible, so intellectual, so logical.

Both books seem to exemplify the validity of a remark of Herbert Deane in his book on Augustine: As history draws to its close, the number of true Christians in the world will decline rather than increase. His (Augustines) words give no support to the hope that the world will gradually be brought to belief in Christ and that earthly society can be transformed, step by step, into the kingdom of God. The anti-Christ figure in The Lord of the World becomes the Man-God, the Lord of the World, precisely by promising universal brotherhood, peace, and love, but no transcendence.

The hero of the book is an English priest, Percy Franklin, who looks almost exactly like the mysterious Julian Felsenburgh, who is an American senator from, yes, Vermont. Felsenburgh suddenly appears as a lone and dramatic figure promising the world goodness if it but follow him. No one quite knows who he is or where he is from, but his voice mesmerizes. Under his leadership, East and West join. War is abolished. Felsenburgh becomes the President of Europe, then of the World, by popular acclaim. Everyone is fascinated by him. Still no one knows much about him. People are both riveted and frightened by the way he demands attention. Most follow without question.

The only people who oppose him in any way are the few loyal Catholics. These two adjectives beg the question. When and if times of persecution come, will you and I be counted among the few and the loyal? Can we be so counted today?

The last words of the novel are well, you have it in your hands. Continue reading and you will find out. Rest assured, however, that they could not be more dramatic, or more moving. Somehow, I no longer find those words so frightening. Rather, they are almost consoling.

James V. Schall, S.J.

Santa Clara, 2016

This foreword is an edited and adapted version of a longer essay which first appeared on the website www.insidecatholic.com on March 9, 2009.

I AM perfectly aware that this is a terribly sensational book, and open to innumerable criticisms on that account, as well as on many others. But I did not know how else to express the principles I desired (and which I passionately believe to be true) except by producing their lines to a sensational point. I have tried, however, not to scream unduly loud, and to retain, so far as possible, reverence and consideration for the opinions of other people. Whether I have succeeded in that attempt is quite another matter.

Robert Hugh Benson

Cambridge, 1907.

P ERSONS WHO DO not like tiresome prologues, need not read this one. It is essential only to the situation, not to the story.

R.H.B.

Y OU MUST give me a moment, said the old man, leaning back.

Percy resettled himself in his chair and waited, chin on hand.

It was a very silent room in which the three men sat, furnished with the extreme common sense of the period. It had neither window nor door; for it was now sixty years since the world, recognising that space is not confined to the surface of the globe, had begun to burrow in earnest. Old Mr. Templetons house stood some forty feet below the level of the Thames embankment, in what was considered a somewhat commodious position, for he had only a hundred yards to walk before he reached the station of the Second Central Motor-circle, and a quarter of a mile to the volor-station at Blackfriars. He was over ninety years old, however, and seldom left his house now. The room itself was lined throughout with the delicate green jade-enamel prescribed by the Board of Health, and was suffused with the artificial sunlight discovered by the great Reuter forty years before; it had the colour-tone of a spring wood, and was warmed and ventilated through the classical frieze grating to the exact temperature of 18 Centigrade. Mr. Templeton was a plain man, content to live as his father had lived before him. The furniture, too, was a little old-fashioned in make and design, constructed however according to the prevailing system of soft asbestos enamel welded over iron, indestructible, pleasant to the touch, and resembling mahogany. A couple of book-cases well filled ran on either side of the bronze pedestal electric fire before which sat the three men; and in the further corners stood the hydraulic lifts that gave entrance, the one to the bedroom, the other to the corridor fifty feet up which opened on to the Embankment.

Father Percy Franklin, the elder of the two priests, was rather a remarkable-looking man, not more than thirty-five years old, but with hair that was white throughout; his grey eyes, under black eyebrows, were peculiarly bright and almost passionate but his prominent nose and chin and the extreme decisiveness of his mouth reassured the observer as to his will. Strangers usually looked twice at him.

Father Francis, however, sitting in his upright chair on the other side of the hearth, brought down the average; for, though his brown eyes were pleasant and pathetic, there was no strength in his face; there was even a tendency to feminine melancholy in the corners of his mouth and the marked droop of his eyelids.