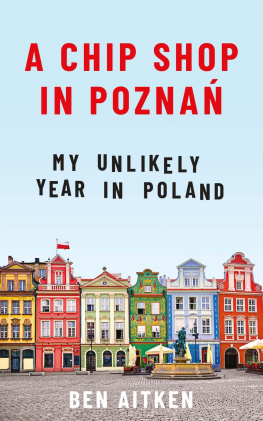

8 March 2016 . I decided to move to Poland in the sauna. It seemed sensible. I had seen Poles in Peterborough and Portsmouth and the Cotswolds and I had followed the conversation about whether there were too many in the UK or too few, whether they were doing all the work or none at all. I wanted to know why the Poles a notoriously patriotic people were leaving home in their millions. I am also contrary by nature and design, so the idea of going the other way, of being a British immigrant in Poland, was appealing. Also appealing was the idea of being elsewhere. I had grown tired of Great Britain. Its comforts were a pain. Its nice routines were doing nothing for me. I wanted to be alone and abroad and innocent and curious, to have my character reset, my faults unknown, to find stories in buildings, stories in people, to be childish once more, to be again at the beginning. Moving to Poland is not the only way to deal with a case of itchy feet. I might have moved to the Falkland Islands. But if Britain chooses to leave the European Union in three months time (a referendum is in the diary) my freedom to move and work and love and learn in twenty-odd countries will be irrevocably lost. Make hay while the sun shines.

Four days after the sauna I flew to Pozna. I chose Pozna because I had never heard of the place and it was the cheapest flight. I didnt want to move to Warsaw or Krakow, where there would be plenty of English speakers. Id had enough of those. A friend had been on a stag do in Krakow. He was able to consume things that were pronounceable, to take trams and taxis in the right direction, to convince a pair of police officers he had no idea throwing kebab meat at the statue of a Nobel Prize winner wasnt de rigueur. (Despite all their practice, the British dont travel well.) He did all these things in English, of course. Polish wasnt necessary to get by. I didnt want that cushion. If I was caught throwing fast food at a national treasure, I would like to defend myself in the local tongue. It would show respect. In short, I wanted to feel that I was fully elsewhere. I wanted to be an alien. We are here to go somewhere else, said the writer Geoff Dyer.

Eastern Energy, Western Style it says in baggage reclaim. What does that even mean? Is Poland on the fence? Is it caught in two minds? Poland was a communist country for 50 years until the early 90s, under the thumb of Russia. It was forced to look east. But now what? I dont have anything to reclaim or claim for that matter so spend time in front of touchscreen info-points that issue warnings and invitations. The city is its brands, says the screen, before showing a list of popular retailers. West, indeed.

On the 59 bus I see international brands like old foes, with their inevitable flags and packaging, then a World Trade Centre, squat and beige and laughably low-key, a mile shorter than the one that famously fell. Then endless residential blocks in lime and butter, mint and pink, colour an apology for form, stubbornly stretching along Bukowska Street. The buss upholstery and layout and adverts beg questions. Simple things, suddenly odd. There is nothing remarkable about the bus or the journey, and yet I am transfixed. A slideshow of paintings by Delacroix and Hockney, of peasants and swimming pools, couldnt hold my attention more tightly. And so it starts, I think, the endless enquiries of the uprooted, the keen eyes of the replaced. I am delighted to feel the questions come on, after months of stale thinking at home, that well-loved place that I often long for, but more often long to betray. Oikophobia is a chronic inclination to leave home. Im a first-class oik. Home is Clive Road, Portsmouth, England, Britain. Portsmouth was built to build ships that no longer need building. Charles Dickens was born there but moved to London when he was five, already tired of the place. The football club and the sea give people something to look at. Thats all you need to know about home.

If ignorance is bliss then Im in for a good time. I know absolutely nobody in Poland and know nothing of the language. Is it the Roman alphabet? Is there even an alphabet? Perhaps the alphabet was destroyed in the war, along with the rest of the country. In any case, moving to Poland will be rejuvenating. If I work hard over the next year, Ill be able to speak Polish as well as a three year old. The idea appeals to me. Three year olds are some of the happiest people I know. My niece is three. Shes ecstatic. She gets a thrill out of the simplest of things, like waking up or tying her laces. Maybe being effectively three wont be such a bad thing. Maybe it will teach me a few things. There is much said or written about travel improving or stretching a person. Didnt she grow! they say. Less is said of travel reducing a person, infantilising them, making a child of them, and how it does them a service thereby.

Even an innocent needs to break the ice. I had bought a phrase book at the airport in London, had committed a few phrases to heart over Germany. By the time I landed I knew how to say I love you, that I am happy or sad, that something is beautiful or ugly. I would live a binary existence, a yes-or-no lifestyle (not unfashionable these days), surely preferable to a life on the fence, to considering all things alright. It would be liberating to leave such a linguistic centre-ground, such a diplomatic no mans land. I look forward to tapping a stranger on the shoulder and pointing to a child riding a bike for the first time and saying, That is not ugly, I love you.

The bus terminates outside Planet Alcohol and Mr Kebab. Scanning around for bearings, it is apparent that Polish words are longer than average. Most look like Wi-Fi passwords, anagrams to be unscrambled, encryptions to be cracked. No wonder that a lot of the groundwork for the Enigma codebreaking machine was done by Poles. Untangling is in the genes. One of the reasons that Polands economy is notoriously sluggish, I would like to think, is because everyone is staring at memos and instructions and agendas and emails wondering what on Gods earth is meant by them. no two ways about it, it will be a hard language to learn. Not only must I learn new letters e and a and o and s and c have alternatives that are accessorised with tails and fringes but I must also contend with familiar letters arranged in new ways, with the result that when one finds oneself in front of a door, and is invited to pcha, one doesnt know whether to push or pull. Moreover, faced with such an impassable door, such a language barrier, one is unable to ask a passer-by to clarify the situation, for their instruction Push it and see, you immigrant! is bound to be equally senseless. An alien in Poland, therefore, can reliably be found stranded before some portal or another, wishing (in English) that it were automated.

I check in at a hotel on Freedom Square then go to a nearby information point. The women at the information point cant answer my questions about registration, health insurance, benefits. They dont seem able to deal with someone long-term. But when are you going home? they ask. When does your holiday end? What they can tell me is where a bank is. I go there for a short interview, during which Im offered coffee and a translator. If this is the face of Polish bureaucracy, its a face I could get used to. It wasnt always thus. Michael Moran was not offered coffee. By his account A Country in the Moon, which remembers the authors time helping Poland convert to capitalism in the early 90s it took Michael seven months to post a letter. A country in the moon refers to a remark made by Edmund Burke at the end of the 18th century, when Poland was taken off the map by Austria and Russia and Prussia, and then put on the moon, where it remained until 1919. It was an extraordinary historical circumstance, an exceptional vanishing act, a momentous dislocation. I bet the Polish people remember the moon days keenly.

![Ben Aitken [Ben Aitken] A Chip Shop in PoznaЕ„](/uploads/posts/book/140582/thumbs/ben-aitken-ben-aitken-a-chip-shop-in-poznae.jpg)