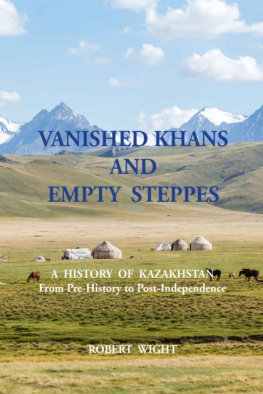

Kazakhstan

Surprises and Stereotypes

After 20 Years of Independence

JONATHAN AITKEN

Published by the Continuum International Publishing Group

The Tower Building | 80 Maiden Lane |

11 York Road | Suite 704 |

London | New York |

SE1 7NX | NY 10038 |

www.continuumbooks.com

Jonathan Aitken, 2012

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission from the publishers.

First published 2012

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 978-1-4411-1794-6

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress.

Typeset by Fakenham Prepress Solutions, Fakenham, Norfolk NR21 8NN

To Anuar Adilbekov

My twenty-four year old Kazakh Godson whose youthful ambition, fluent English, Bolashak scholarship and dedication to public service symbolizes all that is best in the rising generation of his country.

Contents

Acknowledgements

When I completed my last book, Nazarbayev and the Making of Kazakhstan one or two friends suggested that I should consider a sequel. Their idea was that having written the first Western biography of the President I should try to create a portrait of the country.

I was intrigued by the idea for two reasons. First, I find the Kazakhstanis an attractive people who are building a nation that has many more surprising aspects to it than most foreign writing suggests. Secondly, I have become mildly irritated by the out of date stereotypes of Kazakhstan which are repeated too easily in the international media.

So this book is my authors attempt at capturing the new spirit of contemporary Kazakhstan. Inevitably it is a subjective portrait but inspired by so many experiences and individuals that I hope there is plenty of objectivity too! The responsibility for all reporting and commenting is entirely my own. But after interviewing (in the course of both books) over one hundred sources, one or two figures stand out to whom I express special gratitude. The first is President Nursultan Nazarbayev whose willingness to give me over 35 hours of one-on-one interviews has been matched by his openness, his humour and his unique perspectives.

Secondly, I thank Erlan Idrissov, former Foreign Minister of Kazakhstan, former Ambassador in London and now his countrys Ambassador in Washington DC. He is an electrifyingly effective bridge builder of understanding between Western minds and Kazakhstani minds. To him and his colleagues at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs I am particularly grateful, not least for the in-country hospitality they arranged for me.

Kazakhstan is a young country increasingly driven by its younger generation. I have talked and enjoyed hospitality with many of them. One became such a good friend that he is now my adopted Kazakh Godson. He is 24 year old Anuar Adilbekov, a Bolashak scholar who has spent much of the past year studying at Essex University in Britain. We first met in Stepnogorsk prison when he was accompanying me on a tour of Kazakh jails as the representative of his boss Marat Beketayev (another special friend) who is Executive Secretary of the Ministry of Justice. Because Anuar Adilbekov is such a symbolic representative of the talented rising generation of Kazakhstan this book is dedicated to him and to them.

Most of the typing of the book was carried out by Rosemary Gooding with extra help from Helen Kirkpatrick and Susanna Jennens. To all of them my warm thanks. For useful research work I am grateful to Anuar Adilbekor and to my daughter Victoria Aitken

I also thank my publishers, Continuum, particularly Robin Baird-Smith and Rhodri Mogford.

Finally, the greatest gratitude of all goes to my beloved wife Elizabeth who gracefully tolerated my absences from home on visits to Kazakhstan and encouraged me on every step of my authors journey.

JONATHAN AITKEN

London, July 2011

Towards a New National Identity

Towards a New National Identity

Writing about contemporary Kazakhstan is like making a journey into unexplored territory, for it is one of the least known yet most surprising nations of the post Soviet world. It may be a timely moment to offer a portrait of this new country as it passes the historical milestone of its twentieth anniversary as an independent state.

At the time of Kazakhstans premature birth into independence, conceived amidst the chaos of the Soviet Unions disintegration in December 1991, the consensus of opinion held that the infant nation was too poor and too politically unstable to survive. This view, later encouraged by ridicule from the movie Borat, prevailed for several years.

Today the international community takes Kazakhstan seriously because of its growing economic importance. Yet even now most westerners know little or nothing about its history, culture, character and future potential. Nevertheless there is a growing understanding that a new powerhouse is coming of age on the Steppes. At this strategic crossroads where Chinese, Russian, Central Asian and Western civilizations converge, Kazakhstan has arrived as a stable and significant nation state.

One sign of the changing times is that international recognition of Kazakhstan is rising. From its hosting of the OSCE summit to the performances of its acclaimed orchestras and musicians, the country is making its mark on the world stage. Its economic power to move oil markets, stock markets, grain markets and the world uranium market is well known to global traders. Kazakhstanis themselves are becoming more confident as they travel and study abroad in large numbers. This is a nation on the move.

Kazakhstans governance and politics are interesting too, although you would never guess it from the lazy reporting of too much of the worlds media. Stereotypes and clichs abound, among them police state; ruthless dictatorship; sinister regime; and even worse than North Korea. Forgive them their press passes! This author has been able to report from the countrys darkest corners, such as its prisons and security services; on its brightest scholars and students; on its cultural show pieces of theatre, ballet and music; from its rural auls; its intellectual schools; its richest industries; its liveliest young entrepreneurs; its two greatest cities and in interviews with its most prominent public figures. At the end of such a writers journey I have no complaints about lack of access or openness. As a result, this book contains some criticisms, some compliments, and many fresh insights. The most intriguing discovery is the emergence of a new national identity.

Portraying the national identity at the time of Kazakhstans twentieth anniversary is challenging because the picture is not static. So much in the country is developing and changing fast. Yet for all its growing wealth, the nations most important resource is its people. They are a combination of the talented and the traditional, full of futuristic ambition yet with deep roots in their ancestry and culture. Defining these roots is difficult because they are a fusion of ancient Steppe values; Turkic-Islamic heritage; and the testing experiences of Soviet colonisation. To understand Kazakhstans past and potential, three themes are surprisingly important: Suffering, Survival and Success.