Contents

Guide

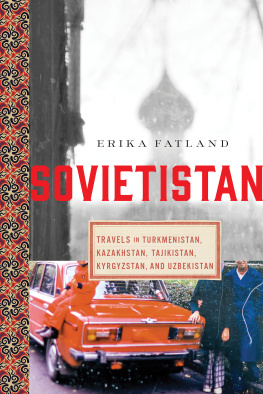

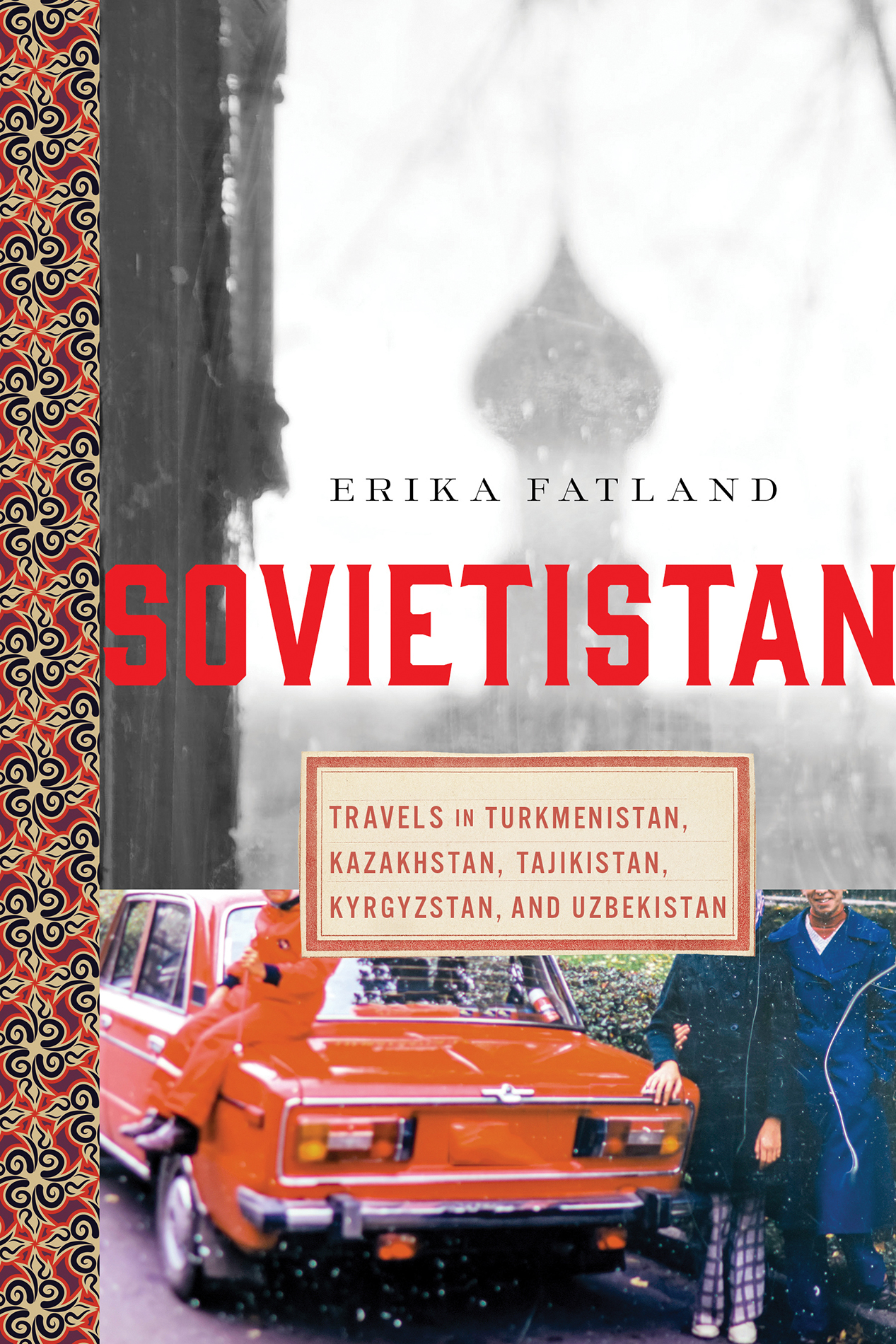

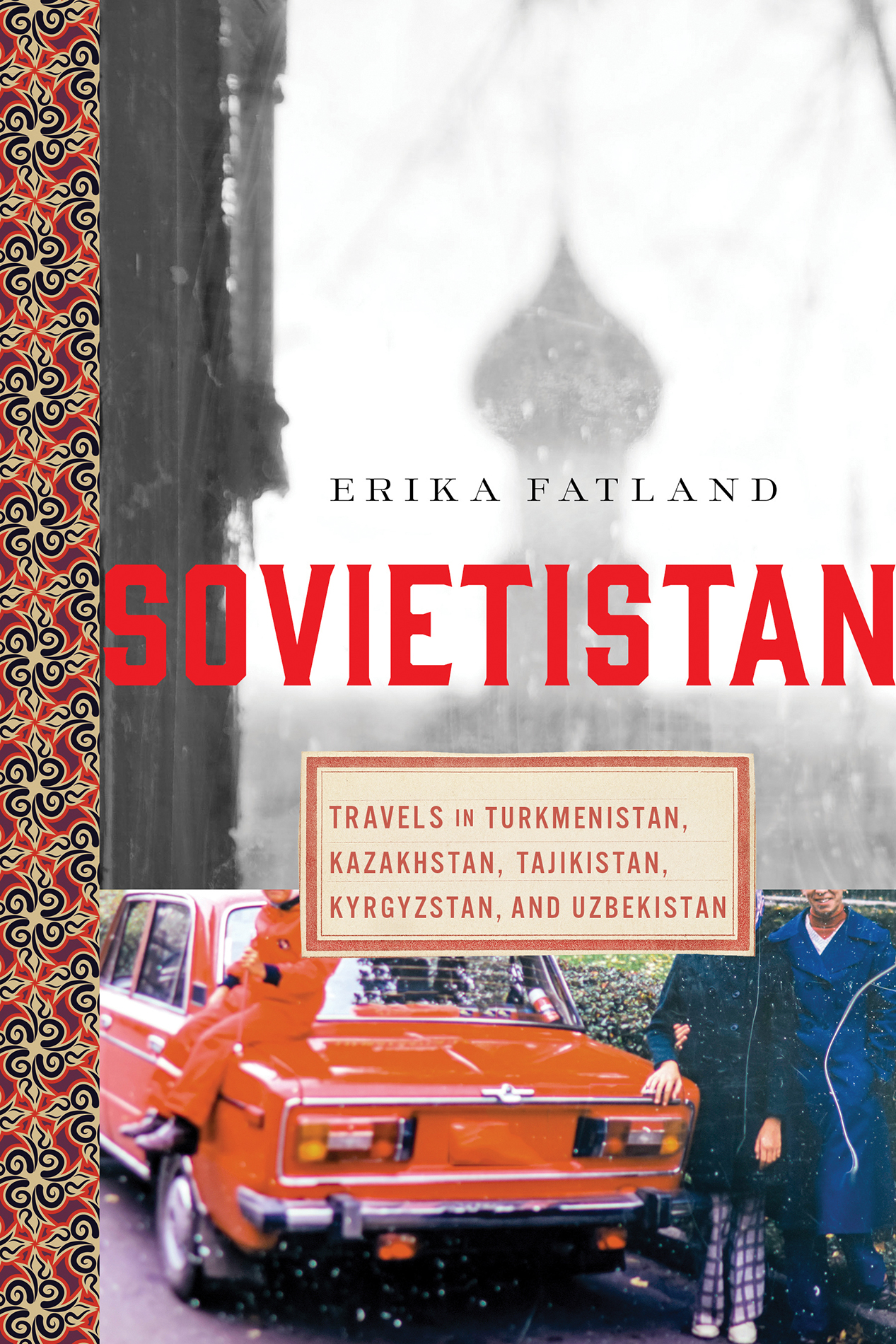

SOVIETISTAN

TRAVELS IN TURKMENISTAN, KAZAKHSTAN,

TAJIKISTAN, KYRGYZSTAN, AND UZBEKISTAN

ERIKA FATLAND

Translated by Kari Dickson

S OVIETISTAN

Pegasus Books, Ltd.

West 37th Street, 13th Floor

New York, NY 10018

Copyright 2020 by Erika Fatland

Translation 2020 Kari Dickson

First Pegasus Books hardcover edition January 2020

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in whole or in part without written permission from the publisher, except by reviewers who may quote brief excerpts in connection with a review in a newspaper, magazine, or electronic publication; nor may any part of this book be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or other, without written permission from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

ISBN: 978-1-64313-326-3

ISBN: 978-1-64313-379-9 (eBook)

Distributed by W. W. Norton & Company

the collapse of Russian rule in Central Asia has tossed the

area back into a melting pot of History.

Almost anything could happen there now, and only a brave

or foolish man would predict its future.

Peter Hopkirk

The Great Game. On Secret Service in High Asia , 2006

Central Asian names, both personal and place names, are often confusing for western readers. Not only do they sound unfamiliar to us, but many of them have reached our own language via Russian, which was the dominant language of the Soviet Union. The names and spellings have thus been further complicated by Russian transcription rules. Another issue is that, since the dissolution of the Soviet Union, many places have been given new names, for example, Krasnovodsk in Turkmenistan is now called Turkmenbashi, and the capital of Kyrgyzstan, Bishkek, was formally known as Frunze.

With very few exceptions, I have used the new place names in this book. One exception is Semipalatinsk in Kazakhstan, which is now called Semey. I have written about historical events that took place here when the town was called Semipalatinsk, so I have chosen to use the Russian name.

I am lost. The flames in the crater have erased the stars and then drained all the shadows of light. The fiery tongues hiss and spit; there are thousands of them. Some are as big as a horse, others no bigger than raindrops. A gentle heat strokes my cheeks; there is a sweet, sickly odour. Stones loosen from the edge and tumble into the flames without a sound. I step back onto firmer ground. The desert night is cold, without fragrance.

The burning crater was created by accident in 1971. Soviet geologists believed that the area was rich in gas and so started to bore-test. And they did indeed find gas, a vast reservoir. Plans were immediately drawn up for large-scale extraction. But then one day the ground opened under the rig, like a great grin, some sixty metres long and twenty metres deep. Foul-smelling methane gas poured out from the crater. All drilling was put on hold, the engineers and geologists packed their bags and struck camp. In order to reduce any risk to the local population, who, several kilometres away, had to hold their noses because of the nauseating smell of methane, it was decided that the gas should be burned off. The geologists estimated that this would take a matter of days or weeks.

Eleven thousand and six hundred days later, more than three decades, in other words, the crater is still burning furiously. The locals used to call it the Door to Hell. But there are no locals anymore. The village was evacuated by Turkmenistans first president, who did not want tourists visiting the crater to see the miserable conditions there, so all 350 inhabitants were moved elsewhere.

The first president is no longer there, either. He died two years after the village was cleared. His successor, the dentist, has decided that the crater should be filled in, but, as yet, no-one has lifted a single spade to fill in the Door to Hell, and the methane gas is still escaping from its apparently inexhaustible underground reserve through thousands of tiny holes.

I am swallowed by the dark. All I see are dancing flames and billowing, transparent gas that lies like a lid over the crater. I have no idea where I am. Gradually I start to pick out stones, ridges, stars. Tyre tracks! I follow the tracks for a hundred metres, two hundred metres, three hundred metres; gingerly I feel my way forwards.

From a distance the gas crater is almost beautiful: thousands of flames that melt together to become an oblong, orange fire. I walk slowly on, following the tracks, and stumble across another set of tyre tracks, and then some more, which criss-cross each other: fresh, deep and damp tracks, and dry, worn, dusty ones. There is little help to be had from the stars which now fill the heavens like fireflies. I am no Marco Polo, I am a twenty-first century traveller and can only navigate using the G.P.S. on my mobile. But my iPhone lies dead in the pocket of my trousers, so is no help at all. And even if I did have a full battery and reception, I would still be utterly lost. There are no street names in the desert, no point by which to orient oneself.

Two beams of light cut through the night. A vehicle comes hurtling towards me; the noise of the engine is almost brutal. Inside the dark windows I catch a glimpse of peaked caps, uniforms. Have they spotted me? In a wave of paranoia, I think that they are after me. I entered the country, one of the most closed in the world, on false pretences. Even though I have weighed my words and not told anyone why I am here, they must have long ago guessed. No student would come here on a guided tour, alone. A gentle push and I could disappear for ever through the Door to Hell, engulfed and burned to a cinder.

The headlights blind me, and then they are gone, as fast as they came.

I do the only sensible thing. I choose the highest ridge that I can see and scramble to the top in the grey darkness. From up here, the Door to Hell looks like a glowing mouth. The desert stretches away from the crater in all directions, like a melancholy patchwork cover. For a brief moment it feels as if I am the only person on the planet. An oddly uplifting thought.

Then I spot a bonfire, our little bonfire, and head straight towards it.

Gate 504. It had to be wrong. All the other gates were 200-and-something: 206. 211. 242. Was I in the wrong terminal? Or worse the wrong airport?

East meets West at Atatrk Airport in Istanbul. The travellers are a glorious gallimaufry of pilgrims on their way to Mecca, sunburned Swedes with bags full of duty-free Absolut Vodka, businessmen in mass-produced suits, white-clad sheiks with black-clad wives weighed down by exclusive European designer bags. No airline in the world flies to as many countries as Turkish Airlines and, as a rule, anyone going to a lesser known capital with an unfamiliar name can expect to change planes here. Turkish Airlines flies to Chisinau, Djibouti, Ouagadougou and Usinsk. And to Ashgabat, which was my destination.

Eventually I spotted the elusive number at the end of a long corridor. 504. As I made my way towards the gate, which seemed to move further away the closer I got, the crowds of people thinned. Until finally I was alone, at the furthest end of the terminal, in an out-of-the-way corner of Atatrk Airport to which only a handful have been. The corridor ended in a wide staircase. I descended into a world of colourful headscarves, brown sheepskin hats, sandals and kaftans. I was the one who stood out in my waterproof jacket and trainers.