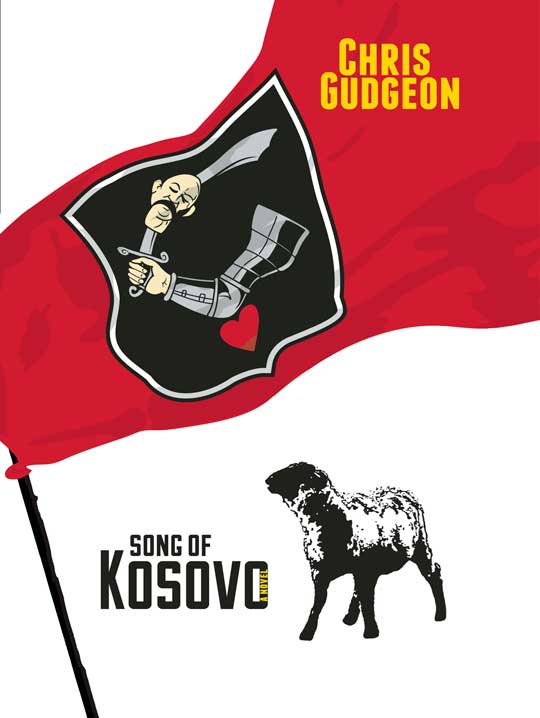

Song of Kosovo

Also by Chris Gudgeon

Fiction

Greetings from the Vodka Sea

Non-Fiction

Ghost Trackers: The Unreal World of Ghosts, Ghost-Hunting and the Paranormal

Stan Rogers: Northwest Passage

The Naked Truth: The Untold Story of Sex in Canada

Luck of the Draw: True Tales of Lottery Winners and Losers

Consider the Fish: Fishing for Canada from Campbell River to Petty Harbour

Out of This World: The Natural History of Milton Acorn

Beyond the Mask: The Ian Young Goaltending Method, Book II (with Ian Young)

An Unfinished Conversation: The Life and Music of Stan Rogers

Behind the Mask: The Ian Young Goaltending Method (with Ian Young)

Humour

Youre Not as Good as You Think You Are: A Demotivational Guide (with Sugar Ray Carboyle)

Copyright 2012 by Chris Gudgeon.

All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher or a licence from the Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright). To contact Access Copyright, visit www.accesscopyright.ca or call 1-800-893-5777.

Edited by Bethany Gibson.

Jacket and page design by Julie Scriver.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Gudgeon, Chris, 1959

Song of Kosovo / Chris Gudgeon.

Issued also in print format.

ISBN 978-0-86492-748-4

1. Kosovo War, 1998-1999 Fiction. I. Title.

PS8613.U44S66 2012 C813.54 C2012-902937-8

Goose Lane Editions acknowledges the generous support of the Canada Council for the Arts, the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund (CBF), and the Government of New Brunswick through the Department of Culture, Tourism, and Healthy Living.

Goose Lane Editions

500 Beaverbrook Court, Suite 330

Fredericton, New Brunswick

CANADA E3B 5X4

www.gooselane.com

In loving memory

Paul

Barb

Jess

Historical sense and poetic sense should not, in the end, be contradictory, for if poetry is the little myth we make, history is the big myth we live, and in our living, constantly remake.

Robert Penn Warren

Prelude

IT WAS THE SUMMER of 2001, and through an odd set of circumstances I found myself in a barren office building in the ancient and melancholy city of Pritina, capital of what is now recognized (by most people outside the Serbian sphere) as the Republic of Kosovo. The office building was literally in the shadow of the Sahat Kullan, the rococo clock tower that dated back to the waning days of the Ottoman Empire, and I spent many collective hours watching French soldiers from KFOR beetling over the tower they had taken it upon themselves to replace the clocks rusted mechanical works with a state-of-the art electrical system when I should have been collating and archiving a mountain of mildewed files. I had come to Pritina, a youngish man seeking some kind of calculated adventure, and was swept up instead in the chalky underworld of the office functionary.

Our job was simple. Working with a small team of translators and admin staff, we were to organize tens of thousands of documents that had been collected by the advancing Kosovo Force KFOR for short the NATO peacekeepers charged with restoring order within Kosovo while making sure that the integrity of the proto-countrys borders remained intact.

x

It could have been mind-numbingly dull work, but given my training as a social historian, and my natural inclination toward task-centred solitude, I dissolved into a minor dreamlike joy. My days took on a tidal rhythm: mornings and afternoons quietly huddled in my work cubicle, surrounded by a Berlin Wall of files; domestic solitude in the evenings, alone in a Spartan flat a few hundred metres from the office. I came, in time, to see myself as a kind of detective approaching every piece of paper as a potential clue to helping me understand the endless mystery that was, and remains, the Balkans.

Still, it was a tough slog. There were endless lists of names, haphazardly collected so that any sense of context was lost (was it a list of prisoners or dinner guests? Were they the names of schoolchildren whod received their immunizations or members of one of those sports clubs that seem to permeate every level of Balkan society?). There were minutes of this meeting and that (one day, I came upon a treasure trove of documents from the Pritina Horticultural Society, seventy-eight years of motions, bylaws, amendments, citations minutely detailed). There were invoices (thirty-six hundred kilos of ground beef; twenty-seven hundred knitted hats) and memos (Notice to staff: the rolling electrical blackouts will continue until the end of February. In the meantime, please avoid use of kerosene heaters within the premises.) There were seas of affidavits and legal briefs, great rolling rivers of draft manifestos and legislative amendments. There were fragments of sentences, which could have been the beginnings of great literary works or the remnants of shopping lists one could never be sure.

It was amidst this cultural exuviae that I found the Song of Kosovo , although the real credit for the discovery should go to Octavian Rdescu, the Romanian polyglot who headed our translation team. I dont know exactly where or when he found the document, I just know that at some point rather later in my tenure I would sometimes be drawn out of my blinkered reverie by the sound of Rdescu, bivouacked in the cubicle next to mine, laughing discreetly or muttering a mild Romanian oath O Doamne ! over and over again. Eventually, I took the bait and asked him what he was reading.

Pjesma o Kosovu , he said, in flawless Serbian. Song of Kosovo .

It wasnt exactly the title of the document, I came to understand: Rdescu had christened it in the manner of the Serbian epic song-poems he personally revered and considered literature of the highest order.

Thereafter, whenever we were bored or slap-happy from inhaling a toxic mixture of dust mites and Serbic conjugates, Rdescu would read passages of the document, impossibly translating from Serbian to Romanian to English as he went. Ostensibly, it was some kind of affidavit or brief, addressed to a certain Nexhmije Gjinushi (who had for a short time worked, I eventually verified, for the UK the Kosovar Albanian nationalist liberation organization which had begun compiling evidence of war crimes before the final shots in the conflict were fired). But in terms of its content and tone, the Song of Kosovo was like no legal brief I had ever encountered. Even by the standards of jurisprudence, it was long and somewhat rambling, and told a story almost too unbelievable to be true. Then again, as Rdescu never hesitated to remind me, Serbia was a country where the unbelievable was a matter of course, where mere months previously, for example, a wheelbarrow full of dinars could not buy a loaf of bread.

So, Pjesma o Kosovu joined my narrow list of obsessions for the duration of that Serbian summer. I spent hours in my flat with the manuscript laid out on the plywood box that served as both my kitchen table and desk, methodically (and poorly) translating the document from Serbian Cyrillic into something akin to English. It seemed a never-ending pursuit. My output rarely exceeded half a page a day, the progress impeded not only by a morass of idiom and syntax, but by my near-pathological attraction to the trivia, which led me to verify, or at least attempt to verify, even the smallest of details.

Next page