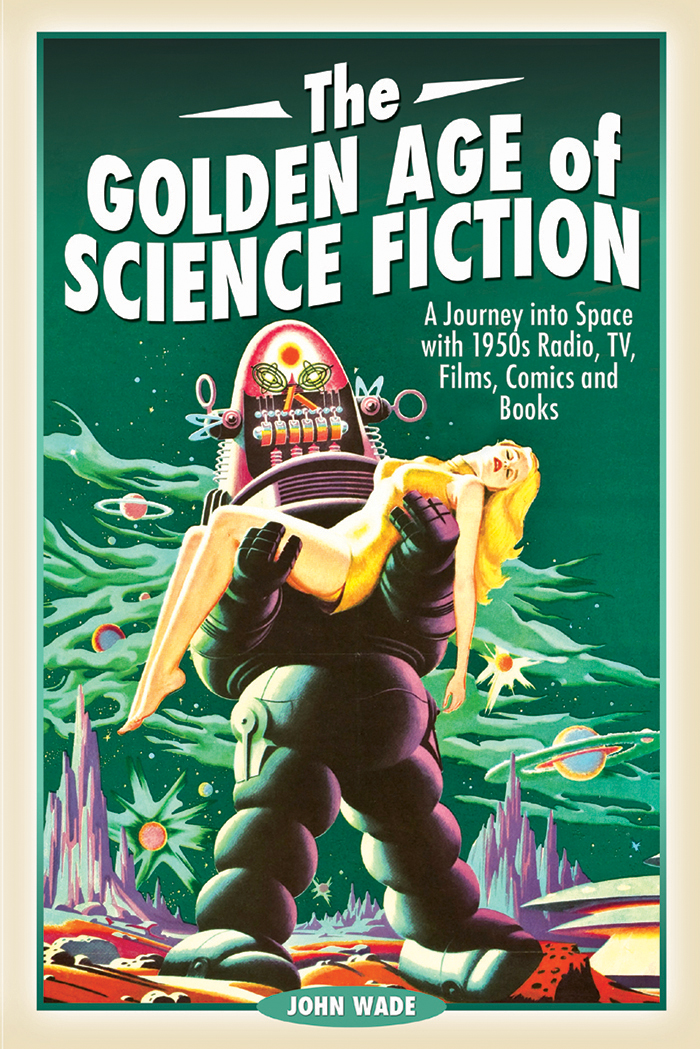

The Golden Age of Science Fiction

The Golden Age of Science Fiction

For everyone who understands the true significance of the words Klaatu barada nikto.

The Golden Age of Science Fiction

A Journey into Space with 1950s Radio, TV, Films, Comics and Books

John Wade

First published in Great Britain in 2019 by

Pen & Sword History

An imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

Yorkshire Philadelphia

Copyright John Wade 2019

ISBN Hardback 978 1 52672 925 5

ISBN Paperback 978 1 52675 159 1

eISBN 978 1 52672 926 2

Mobi ISBN 978 1 52672 927 9

The right of John Wade to be identified as Author of this Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Pen & Sword Books Limited incorporates the imprints of Atlas, Archaeology, Aviation, Discovery, Family History, Fiction, History, Maritime, Military, Military Classics, Politics, Select, Transport, True Crime, Air World, Frontline Publishing, Leo Cooper, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing, The Praetorian Press, Wharncliffe Local History, Wharncliffe Transport, Wharncliffe True Crime and White Owl.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Or

PEN AND SWORD BOOKS

1950 Lawrence Rd, Havertown, PA 19083, USA

E-mail:

Website: www.penandswordbooks.com

Introduction

T he 1950s, many aficionados will tell you, was the golden age of science fiction. But how exactly do you define any golden age? Is it an era when a particular art form reached its peak, and was never subsequently bettered? Or is it the time when you personally first discovered, and became overwhelmed by, a specific genre? For me, it was a little of each.

In 1956, when I was at a somewhat tender age, my mother took me to the cinema to see a film called Ramsbottom Rides Again, staring Arthur Askey, a popular comedian of the day. On the way, we met a neighbour who asked where we were going. When my mother told her, the neighbour took her aside and explained that she should turn straight round and go home. Your son might enjoy the Arthur Askey film, but the second feature will scare the life out of him, she said. Hell have nightmares for weeks.

My mother was never one to readily take other peoples advice, and so we proceeded to the local Odeon.

These were the days when the main film at a cinema was supported by a second feature, sometimes called a B-picture. Usually, these were short films, cheaply made in black and white for the sole purpose of filling out a cinema programme. Sometimes, however, they were films that might have been originally intended as main features, but which didnt quite make the grade. I suspect that the second feature that day, made in garish colour, was one of the latter.

The film had been made in America in 1953, and three years later was doing the rounds of British cinemas as a second feature. It was called Invaders from Mars. The majority of films of this type were rated as X certificate, which, in the 1950s, meant no one under the age of sixteen was allowed to see them. For some reason, this one had crept in under the A certificate category, which meant children could watch the film, providing they were accompanied by an adult.

The Mekon, arch-enemy of Dan Dare, whose comic strip in Eagle each week in the 1950s fuelled the fantasies of so many schoolboys of the era.

It was the first science fiction film I saw and, far from being scared, I was completely awed by it, partly I suspect because the hero was a boy of about my own age who discovers, and fights off, a Martian invasion. I wanted to see more, but unfortunately the X certificate system meant I would not be allowed through the doors of any cinema showing similar films for at least another six years. So it was well into the 1960s before I managed to catch up with reruns of 1950s classics like The Day the Earth Stood Still, Forbidden Planet, This Island Earth and Invasion of the Body Snatchers.

Having discovered science fiction, however, I set out to find other ways to devour it, and soon realised I already had access to one example in Eagle , probably the most popular comic among schoolboys of the 1950s where, on the first two pages, Dan Dare fought weekly battles against dastardly aliens like The Mekon. I immediately persuaded my parents to cancel my orders for comics like Beano, Dandy, Topper and Beezer and switch to the mighty Eagle. Little could I have envisaged all those years ago that one day, carrying out research for this very book, I would find myself in regular contact with a man called Peter Hampson, the son of Frank Hampson, who created and drew the Dan Dare strips; or that I would be privileged to see previously unpublished annotated drawings created by Hampson and his fellow artists as references that ensured the accuracy and continuity of the characters and their surroundings.

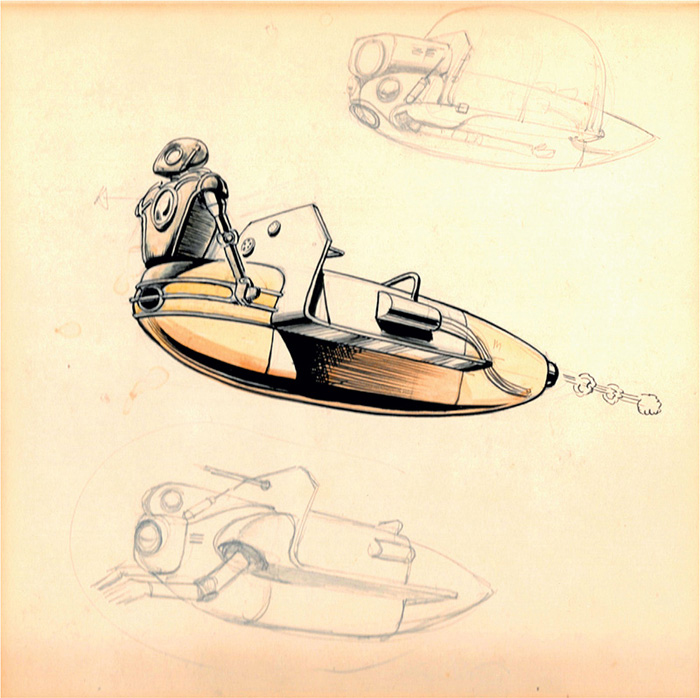

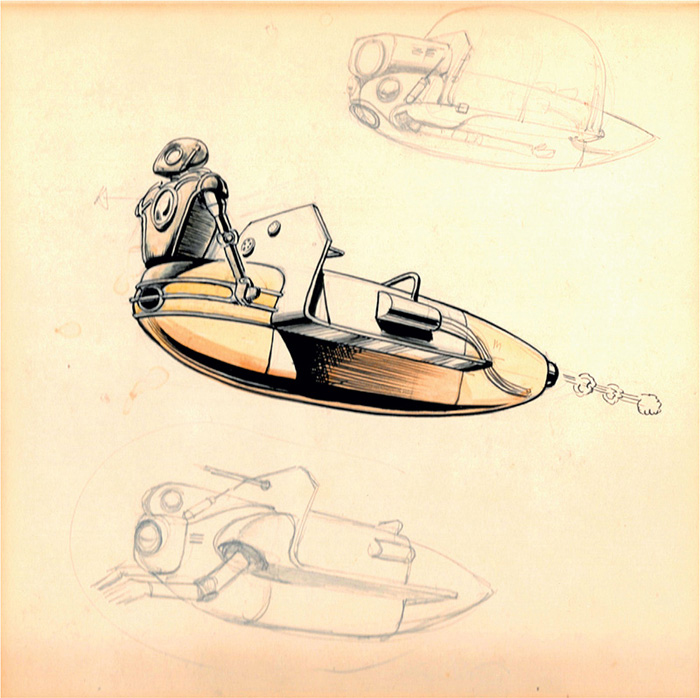

Concept sketch by an Eagle studio artist from around 1957, used to reference characters in the Dan Dare strip.

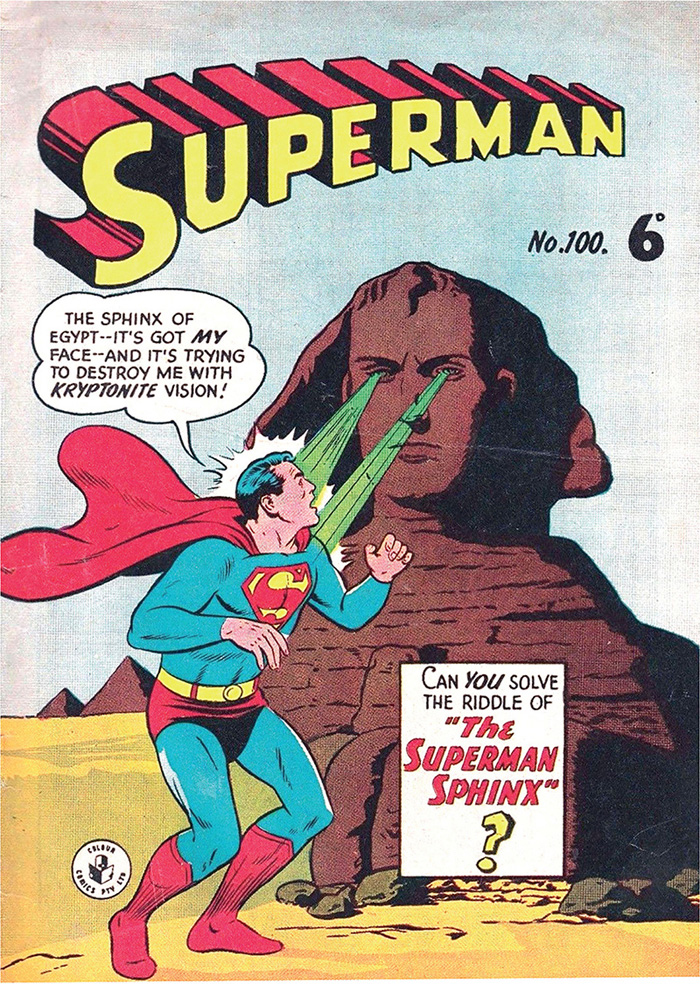

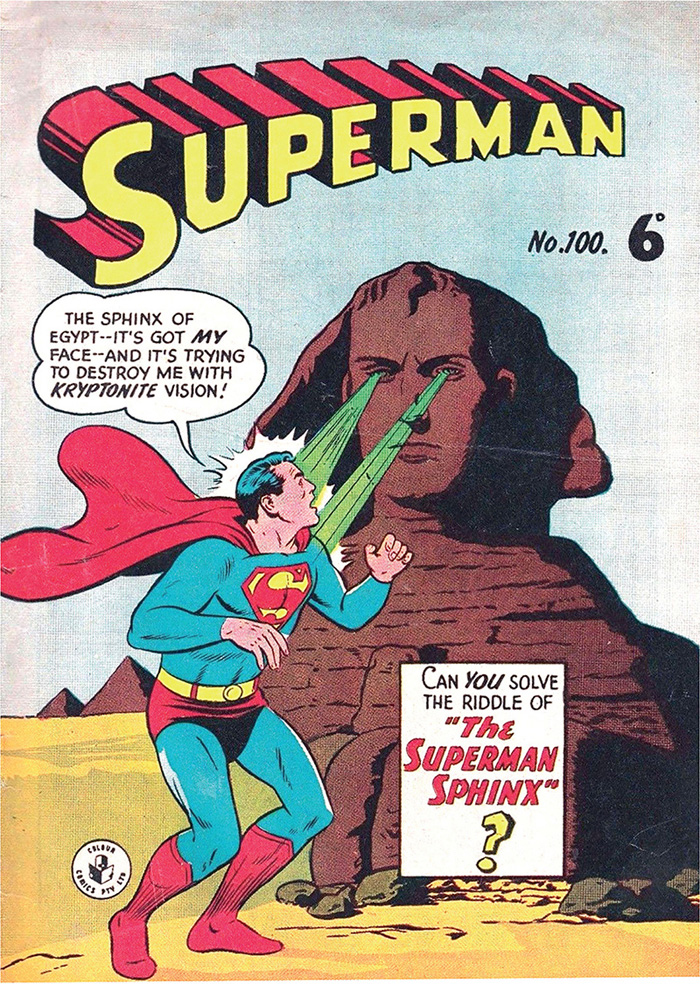

The arrival of Superman comics in the UK was a revelation for budding British science fiction addicts.

I also remembered that I had another example of 1950s science fiction hidden away in my bedroom. It had come courtesy of a fellow pupil in my junior school who had shown me a Superman comic, which I managed to prise from his hands by the simple expedient of swapping it for six copies of Beano . Having read it from cover to cover, I set about worrying every newsagent in town to find another copy, but I can only assume my school friend had had the comic sent to him by someone in America. English newsagents had never heard of Superman, and it was some years more before the comics arrived in the UK.

Meanwhile, there were other places to find science fiction, among them, surprisingly perhaps, on radio or the wireless, as we called it then. On Childrens Hour there were dramatisations of the Angus MacVicar books about Hesikos, the lost planet. And there was the magnificent Journey Into Space, of which, a lot more later. On television there was Quatermass, which unfortunately for me was deemed unsuitable for children. Not that a little thing like that stood in the way of at least one parent who had allowed me to see Invaders from Mars and who permitted me to stay up to see the first instalment though sadly not subsequent episodes of The Quatermass Experiment. Neither did my parents broad-mindedness extend to the 1954 television production of Nineteen Eighty-Four.