SEPARATION AND ABANDONMENT

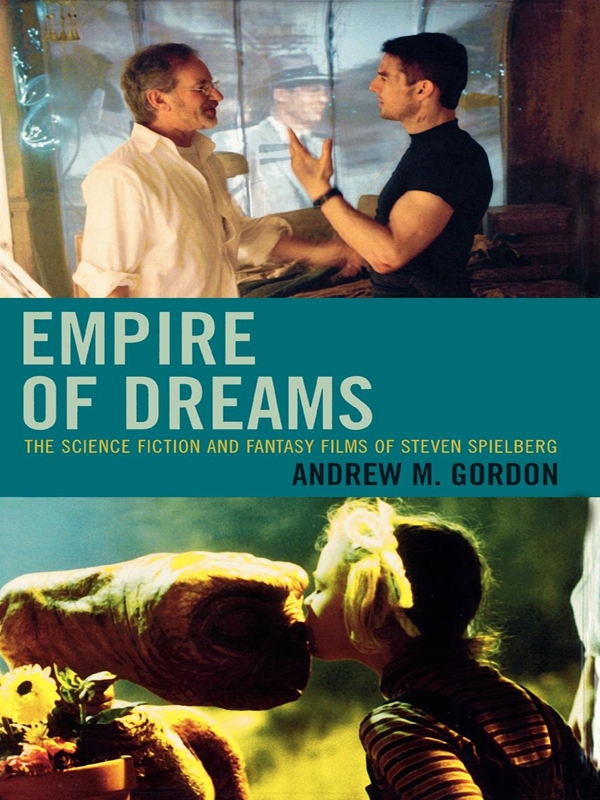

Whether they are SF, fantasy, or more realistic genres, Spielbergs films deal with certain repeated situations: kidnaping or imprisonment, invasion by monsters or aliens, and the stranger-in-a-strange-land facing problems of adaptation and communication.

Certain plot devicesseparation and abandonment, the quest of the parent for the lost child or of the lost child for the parent, and the last-minute rescueoccur in almost every Spielberg movie, and he often makes films about broken homes, families in trouble, and children in peril. Spielbergs suburban trilogydomestic fantasies, cinematic fairy tales about loss, separation, and abandonment, culminating in mother-and-child reunionsare his signature films, in which he forged his characteristic style and subject matter. As I argue, in some ways Close Encounters , E.T., and Poltergeist are so closely linked that they might be considered three versions of the same film, which re-create Spielbergs boyhood home in suburbia and attempt to overcome the shattering of that idyllic existence caused by his parents divorce. He says, E . T . is a film that was inside me for many years and could only come out after a lot of suburban psychodrama (Sragow 108). Elsewhere, he says, The whole thing about separation is something that runs very deep in anyone exposed to divorce. All of us [his entire family] are still suffering the repercussions of a divorce that had to happen. But the whole idea of being taken away from your parents and forced to adapt to a new routineIm not good with change, personally speaking (Forsberg 129). Although these films may stem from his personal trauma, they also speak to the concerns of an increasingly rootless postwar America, with its rising divorce rate.

He has made many other films about being taken away from your parents: either the parents seek the little child lost or the child searches for the lost parents. Even Saving Private Ryan is about a search for a lost boy, Mrs. Ryans sole surviving son. His films often end with joyful reunions or tearful, prolonged farewells: the lost child has been returned to the family or the family must reluctantly part with a loved one. Close Encounters , E.T., Schindler, A.I., and The Terminal combine the family reunion with the protracted farewell, blending the sweet and the sad. Spielberg altered the true story to give Oskar Schindler a more melodramatic final parting from his Jewish family.

Behind the suburban trilogy, Empire of the Sun , and many other Spielberg films, including Schindler, is a childs fear of being separated from family, driven from home, in peril of his life. They are animated by a deep desire for rescue. The little child lost in a nightmare world is a story Spielberg tells over and over, a tale of sentiment and horror, a fairy-tale journey through anxiety and depression into the elation of last-minute rescue. The fear in his films is often counterbalanced by wonder; indeed, the wonder may be a defense against the anxiety.

CHILDREN IN PERIL: TWO SCENES

I want to look at two scenes concerning children in perilone from Close Encounters and another from Schindlers List which epitomize the spectrum of Spielbergs work, from wonder to terror, from dream to nightmare.

The first, from Close Encounters , is the third scene in the movie, a quintessentially cinematic moment without dialogue, just the play of light and sound. The first two scenesin the Mexican desert and in the Indianapolis Air Traffic Control Centerestablish a buildup of strange events worldwide involving UFOs, but the third scene moves the action from the large, public world into an intimate closeup on the domestic uncanny, as aliens invade a typical American household, and it gives us a childs-eye view of the event. Four-year-old Barry Guiler, a blonde-haired, pug-nosed little boy, awakens in his bed in an ordinary midwestern home in Muncie, Indiana, in the middle of the night to unexpected noise and commotion: battery-operated toys suddenly animating themselves. A monkey clangs cymbals, as if heralding something, and Frankensteins pants fall down (a strange contradictiona harmless, comic monster). While toy police cars, with sirens blaring and lights blinking, crash into toy planes, suggesting an emergency, a phonograph turns itself on and plays a childrens song, telling him to Look with care for the shape of a square, suggesting a quest. Wearing a Boston University t-shirt and pajama bottoms with booties (Spielberg carefully grounds his fantasies in such contemporary American details), little Barry goes downstairs to investigate. So the opening images of the scene suggest a monstrous disturbance, an intrusion of the chaotic, the inexplicable, and the uncanny into the everyday, domestic scene, and these mysterious, unseen alien invaders constitute an emergency. There is something monstrous about themyet at the same time a contrary suggestion of something appealingly childlike and comic, so that the little boy is curious rather than fearful.