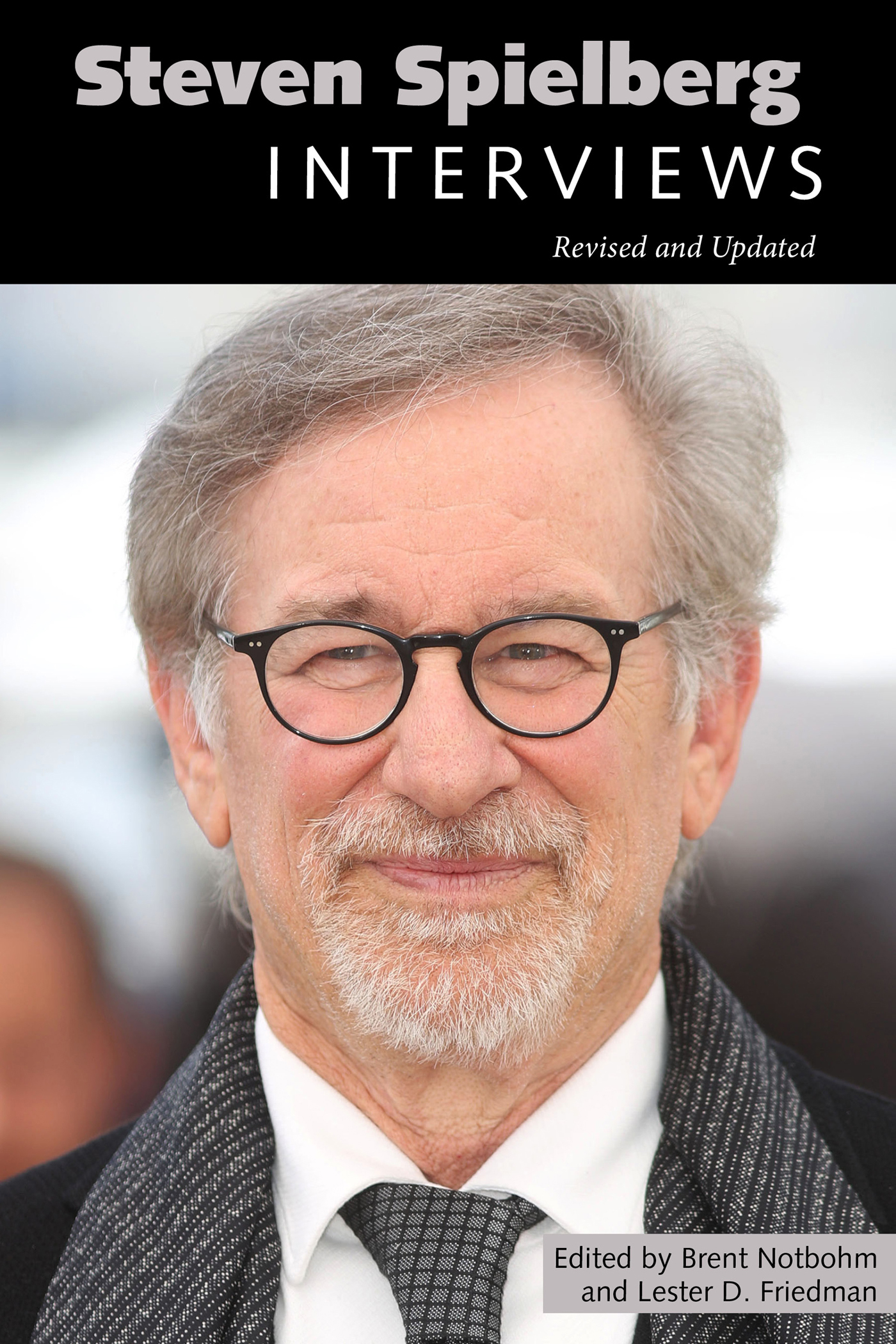

Steven Spielberg: Interviews,

Revised and Updated

Conversations with Filmmakers Series

Gerald Peary, General Editor

Steven Spielberg

INTERVIEWS

Revised and Updated

Edited by Brent Notbohm and Lester D. Friedman

University Press of MississippiJackson

The University Press of Mississippi is the scholarly publishing agency of the Mississippi Institutions of Higher Learning: Alcorn State University, Delta State University, Jackson State University, Mississippi State University, Mississippi University for Women, Mississippi Valley State University, University of Mississippi, and University of Southern Mississippi.

www.upress.state.ms.us

The University Press of Mississippi is a member of the Association of University Presses.

Copyright 2019 by University Press of Mississippi

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

First printing 2019

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Spielberg, Steven, 1946 | Notbohm, Brent, editor. | Friedman, Lester D., editor.

Title: Steven Spielberg : interviews, revised and updated / Edited by Brent Notbohm and Lester D. Friedman.

Other titles: Conversations with filmmakers series.

Description: Jackson : University Press of Mississippi, [2019] | Series: Conversations with filmmakers series | First printing 2019. | Includes index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019003208| ISBN 9781496824011 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781496824028 (pbk. : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781496824035 (epub single) | ISBN 9781496824004 (epub institional) | ISBN 9781496824042 (pdf single) | ISBN 9781496824059 (pdf institutional)

Subjects: LCSH: Spielberg, Steven, 1946Interviews. | Motion picture producers and directorsUnited StatesInterviews.

Classification: LCC PN1998.3.S65 A5 2019 | DDC 791.4302/33092 [B]dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019003208

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data available

Contents

David Helpern / 1974

Andrew C. Bobrow / 1974

Richard Combs / 1977

Mitch Tuchman / 1978

Steve Poster / 1978

Susan Royal / 1982

Susan Royal / 1989

John H. Richardson / 1994

Stephen Schiff / 1994

Peter Biskind / 1997

Stephen Pizzello / 1998

Steve Head / 2002

Spiegel / 2005

Roger Ebert / 2005

Spiegel / 2006

Jim Windolf / 2008

Matt McDaniel / 2011

Will Lawrence / 2013

Cara Buckley / 2015

Josh Rottenberg / 2018

Introduction to the Revised Edition

In the years following our first edition of his interviews, Steven Spielberg has continued to be incredibly productive and has directed some of the most complex movies of his extensive career, including A.I. Artificial Intelligence, Minority Report, Munich, Lincoln, Bridge of Spies, and The Post. Along with these challenging productions, he entertained audiences with the lighter fare of Catch Me If You Can, The Terminal, The Adventures of Tintin, and The BFG, while also plunging into the darker realms of air, land, and virtual reality combat in War of the Worlds, War Horse, and Ready Player One. He directed a much-maligned sequel in the popular Indiana Jones franchise, Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull, and, according to IMDB, yet another sequel will hit movie screens in 2021. Although Spielberg often announces future projects and then produces something totally unexpected, IMDB also notes that he is in preproduction for a remake of West Side Story and the long-anticipated The Kidnapping of Edgardo Mortara, a film set in nineteenth-century Italy about a young Jewish boy raised as a Christian. Both these listings include Tony Kushner, his collaborator on Munich, as the screenwriter. Having celebrated his seventieth birthday on December 18, 2016, Spielberg clearly shows no indications of retiring from directing or, for that matter, of even slowing down his frenetic pace.

In Citizen Spielberg, I approached Spielbergs sprawling directorial output via traditional genre categorizations, demonstrating how his movies fit comfortably within the well-established formats that have characterized American mainstream filmmaking from its earliest silent days, throughout the heyday of the studio system, and continuing into the current configuration of blockbusters and smaller movies. This basic pattern has been maintained in the feature films Spielberg has directed since our first edition: A.I., Minority Report, War of the Worlds, and Ready Player One as science fiction movies; War Horse and Lincoln and to some extent Bridge of Spies as war movies; The Terminal, Munich, and The Post as social-problem movies; and Catch Me If You Can, Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull, and The Adventures of Tintin as action/adventure melodramas. Although fitting within conventional genre categories, Spielbergs features do not simply retread well-worn paths using conventional plots and characters. Instead, they consistently reinvigorate entrenched genre formulations, adding density and depth to what in less creative hands would be simply mundane generic presentations that offer little but the comfort of repetition and the nostalgia of familiarity. As the philosopher and cultural critic Walter Benjamin aptly observed, the uniqueness of a work of art is inseparable from its being imbedded in the fabric of tradition (The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, 1936), and Spielbergs best movies both partake of American cinema history and expand its boundaries.

Many of the defining characters, motifs, tropes, and themes that emerge in Spielbergs earliest movies shape these later works as well, but often in new configurations. Thus, we find man-boys engaging in exciting adventures, images of flight as a constant metaphor for freedom and the unlimited imagination, and male characters filled with fear and angst about their masculinity in a world of changing social conditions. Most consistent of all, Spielbergs narratives remain dominated by shattered families, either biologically related or forced together by dangerous circumstances, but all struggling to reconnect with each other, be they individuals, small enclaves, larger groups of survivors, virtual reality teammates, or the entire American nation. The best films of Spielbergs post-2000 career incorporate these elements as a pathway to probe deeper into more complicated subjects than did many of the previous moviesdangerous technology rather than man-eating sharks, homicidal rather than cuddly aliens, lethal terrorism instead of rampaging dinosaurs. Such movies continue to display a remarkably sophisticated level of artistry that matches, and sometimes even exceeds, the memorable visual hallmarks of his prior work. One wonders if Spielberg perceives these obsessive repetitions and consciously replicates them in film after film or if he somehow remains unaware of these recurring patterns and compulsively reproduces narratives that contain them.

Schindlers List, as many critics have claimed, marked a dramatic turning point in Spielbergs career, both on a personal and a professional level. Its creation compelled him to confront and allowed him finally to celebrate his Jewish identity; at the same time, the films powerful theme and visual artistry finally convinced criticsmany of whom consistently belittled him as an eternal adolescent whose blockbusters (along with those of George Lucas) had transformed Hollywood filmmaking into an amusement park ride rather than a serious art formto reevaluate his imagination and conclude that he was, indeed, a serious artist as well as an inspired entertainer. Such a starkly defining moment in his evolution as an artist was quite publicly highlighted when

Next page