To Charles

HURRAH FOR THE CHOICE OF THE NATION!

OUR CHIEFTAIN SO BRAVE AND SO TRUE;

WELL GO FOR THE GREAT REFORMATION

FOR LINCOLN AND LIBERTY TOO!

Words to a Lincoln campaign song, 1860

Contents

S ome five or six years ago, I received one of the most exciting invitations that ever crossed my desk. The great director Steven Spielberg was asking: would I please join a group of Lincoln scholarsled by my friend historian Doris Kearns Goodwinto spend an entire day talking about Abraham Lincoln. Would I? You bet!

Not long before, Mr. Spielberg had announced that he had acquired rights to Goodwins book Team of Rivals and intended to turn it into a major film. The invitation to join an all-day meeting on Lincoln told me something very important: that the director was going to take this subject very seriously. He had obviously learned a good deal from Doriss bestseller. And now as he began thinking of what aspect to make the focus of his movie, he wanted to learn still more. With her typical generosity, Doris, too, was eager to get her friends and colleagues together.

And this was a generous offer indeed. The scholars would be flown in from all over the country, no matter where they lived, to meet at a luxurious hotel and share breakfast and lunch with Mr. Spielberg and his advisers. My only disappointment was that the meeting wouldnt take place in Hollywood. Instead, it was to be held in Manhattan, only a few blocks south of where I work at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. I wouldnt be flown to Tinseltown after all. I would take a taxi downtown to a building overlooking Central Park (so does my office!).

But the meeting proved amazing anyway. Mr. Spielberg was joined by both his producer and by the brilliant playwright Tony Kushner, who we learned had just signed on to write the screenplay for the new movie. Ill never forget looking on with fascination as Tony unpacked a small leather case, and took from it a full inkwell and some fountain pens, which he lined up in front of him. For the rest of the meeting, he took all his notes the old-fashioned way, with blue ink staining his fingers as he wrote. I expect he wrote the entire movie in this manner.

Over terrific food and wonderful conversation, the six or so of us talked that day about almost everything we knew of Abraham Lincoln: his boyhood, his education, his learning curve on the subject of slavery, his marriage, his children, his life in law and politics, his ability as an orator, and his genius at military strategy. Mr. Spielberg didnt know exactly what part of the Lincoln story he would focus on, so he wanted to hear as much as we would tell him. He sat at the center of a long table, a baseball cap pulled over his head, and asked question after probing question for hours. I like to think we rose to the occasion that day, because he told us the meeting was a real success and he finished it feeling more inspired about his project than ever. I think we only asked him one question all day: how would he film the Gettysburg Address? Would he do a close-up of Lincoln or show the big crowd that was listening to the president?

Here is where we learned the difference between history writing and moviemaking. Without a pause, Mr. Spielberg closed his eyes and began describing an alternative way of presenting the Gettysburg Address: maybe showing a group of children running around the outskirts of the vast audience while Lincoln tries to get the big crowd to hear him, maybe showing the autumn leaves falling from the trees in the wind, maybe not even focusing on Lincoln himself until the endor maybe not at all. We were amazed. No one in the room had ever thought of such an approach. Of course, were not film directors. In the end, Mr. Spielberg chose an entirely differentbut equally originalway to get Lincolns most famous words into the movie. I like to think that we were at least present at the creation.

But there was more to come. In the years that followed, as the Lincoln community continued to buzz about the Spielberg movie, I continued to enjoy a tangential connection to the project, although I never met Mr. Spielberg again and saw Tony Kushner only at events and openings around New York. Happily, my own ongoing adventure with Spielbergs Lincoln included two more chapters. More than a year or two ago, Tony Kushner asked me to read a draft of his beautiful script and alert him to any possible factual errors. What a privilege it was to take the big red notebook home and read every wordtwice. Errors? Very few and very minor, easy to fix. More importantly, Ive never read a stage play or screenplay that more brilliantly captured the real Lincolnhis greatest accomplishments, his elusive personality, and the tension and drama of his final days in the White House.

Finally came one more irresistible invitation: the opportunity to write this book especially for young readers as a companion to the final film. It has been an unforgettable honor to have played even a tiny part in this effort to make history come alive. I can only hope this small book does justice to the geniuses who have brought the movie Lincoln and for that matter Abraham Lincoln himselfto life.

HAROLD HOLZER, AUGUST 2012

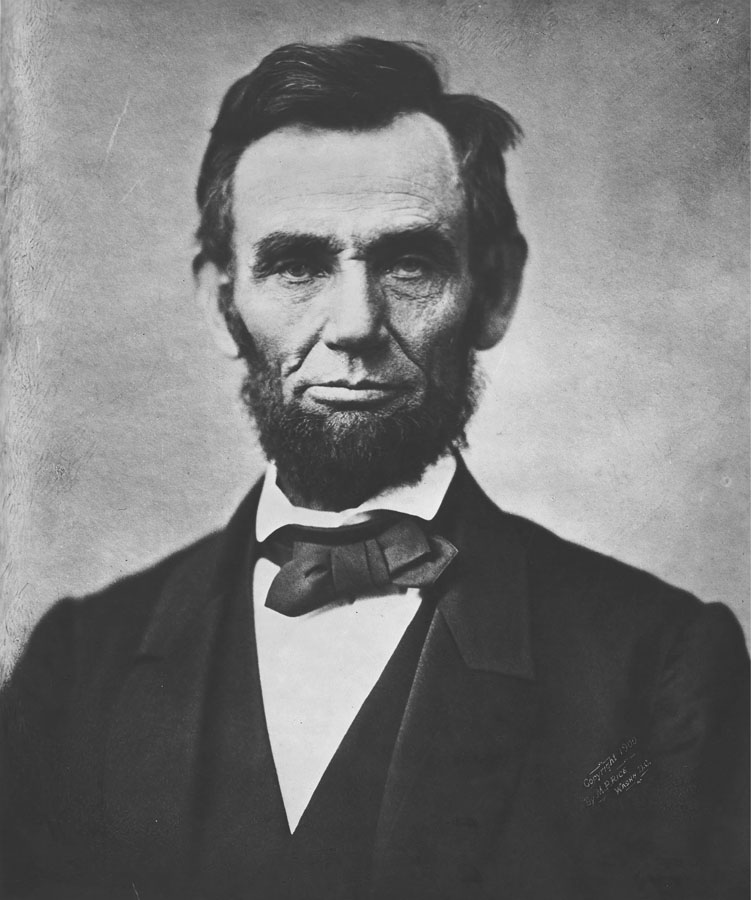

January 31, 1865

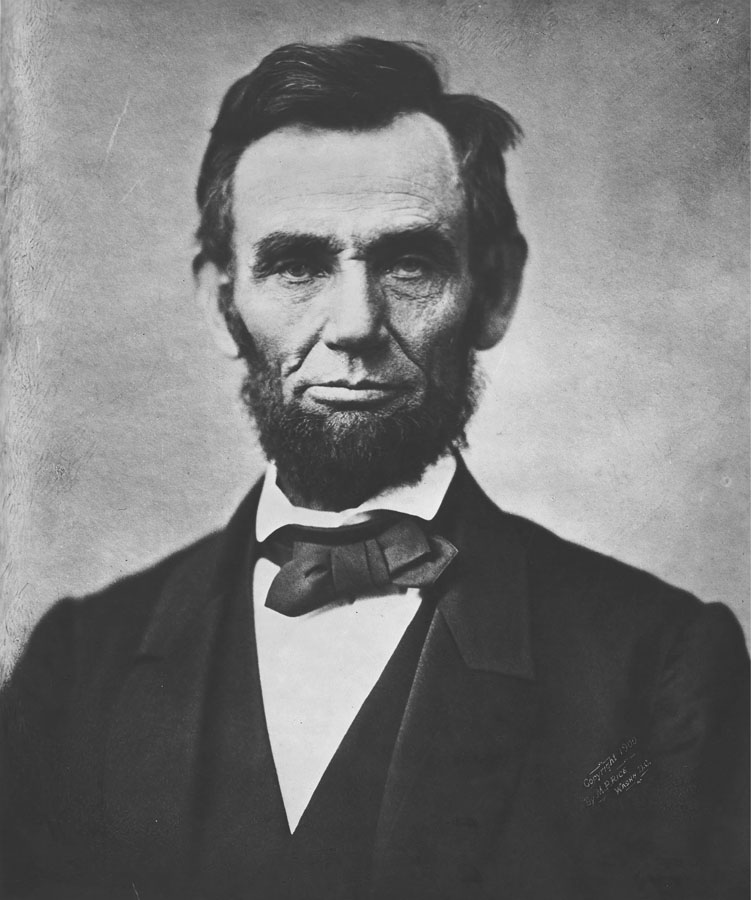

F or weeks, President Abraham Lincoln had waited anxiously for Congress to actwaited, counted votes, held last-minute meetings, made promises, offered deals, and, when necessary, twisted arms. But now, as Lincoln sat in his corner office on the second floor of the White House, he could do nothing more than wait a bit longer for the news to come at last from Capitol Hill, a mile and a half away. Members of the Senate and House of Representatives were finally making their decision. Would Congress vote to approve or reject a Thirteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution that would abolish slavery throughout the United States? The Constitution was the countrys original and most important set of rules and laws. Many Americans believed it should never be altered, and no addition to it had been approved for more than six decades. Lincoln believed that after four years of civil war fought over the issue of human slavery, it was time to remove slavery from America forever.

Just a few months earlier, Lincoln had won a hard-fought campaign for reelection as president. In just a few weeks, he was scheduled to take the oath of office at his second inauguration. In the nerve-wracking days leading up to the historic vote, Lincoln had tried to conduct business as usual at the White House. He welcomed a group of Philadelphia women who had raised great sums of money to care for wounded soldiers. He accepted the gift of a vase made of leaves gathered from the Gettysburg battlefield. He celebrated the Union capture of Wilmington, North Carolina. He began making plans to meet with Confederate leaders on the subject of peace. Lincoln even rode up to the Capitol himselfnot to lobby for passage of the Thirteenth Amendment, but to attend a special concert in honor of the volunteers who helped nurse and feed the troops. There, the president was so touched when a singer named Philip Phillips offered an inspiring tune called Your Mission, he asked to hear it sung one more time. Lincoln always loved a sentimental song. But even music did not make him less nervous about the countrys future, or less determined to fulfill his own mission: to end slavery.

Next page