Table of Contents

The Words of Peace: Selections from the

Speeches of the Winners of the Nobel

Peace Prize

Selected and Edited by

Irwin Abrams

The Words of Gandhi

Selected and Introduced by

Coretta Scott King

The Words of Martin Luther King, Jr.

Selected and Introduced by

Coretta Scott King

The Words of Albert Schweitzer

Selected and Introduced by

Norman Cousins

The Words of Harry S Truman

Selected and Introduced by

Robert J. Donovan

The Words of Desmond Tutu

Selected and Introduced by

Naomi Tutu

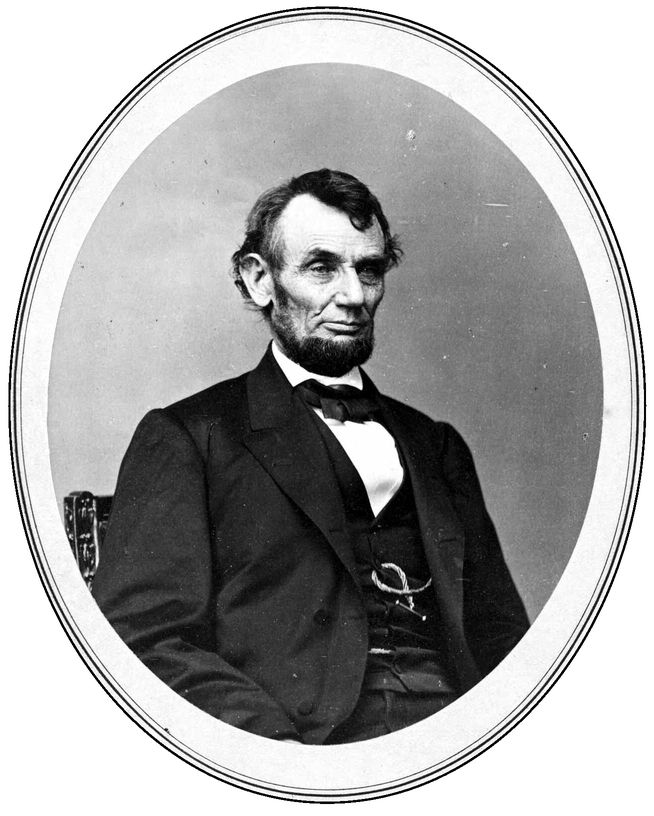

Portrait of Abraham Lincoln, February 9, 1864. Photograph by Anthony Berger of the Brady Studio.

(Courtesy of the Library of Congress, LC-DIG-ppmsca-19204)

Larry Shapiro

I have endured a great deal of ridicule without much malice; and have received a great deal of kindness, not quite free from ridicule. I am used to it. Letter to James H. Hackett, November 2, 1863

In the spring of 1860, Abraham Lincoln wrote to the New York lawyer Charles C. Nott to thank him for editing the text of the Cooper Union Address in preparation for its publication. Nott had made some changes that he considered to be improvements in Lincolns speech. Of course, Lincoln wrote, I would not object to, but would be pleased rather, with a more perfect edition of that speech. Having gotten his polite thanks out of the way, Lincoln went on to say, Some of your notes I do not understand. Of one of Notts changes, Lincoln wrote that it would do little or no harm, although it is not at all necessary to the sense I was trying to convey. Of another, grammatical change, Lincoln conceded that it would certainly do no harm. Another proposed change, however, would be a considerable blunder.

Lincoln summed up his attitude toward Notts editing this way: So far as it is intended merely to improve in grammar, and elegance of composition, I am quite agreed; but I do not wish the sense changed, or modified, to a hairs breadth. And you, not having studied the particular points so closely as I have, can not be quite sure that you do not change the sense when you do not intend it.

A few weeks before Lincoln reviewed Notts editorial work, the one-term former Congressman from Illinois had become the Republican partys presidential candidate. The party had been in existence for only six years and Lincoln was far from a national figure. Presidential candidates were expected to avoid campaigning and speechmaking, so the publication of Lincolns speech would be an important way to convey his ideas and his voice to voters. Considering Lincolns limited education and his reputation as an unpolished country lawyer, we might expect him to have gratefully accepted Notts help. Instead, its possible that no author has ever told an editor to back off with more precision.

Although Lincoln could occasionally express uncertainty about his writing, throughout most of his life he was as confident in his use of language as in his political views. Among the few American presidents who became talented writers, Lincoln is the most improbable. Thomas Jefferson received a gentlemans education, corresponded with philosophers and scientists, and could write at leisure from his estate at Monticello. Theodore Roosevelt, in addition to his Harvard education, lived a life of adventure on the frontier West and wrote articles and books for audiences back East who were fascinated by the places he had been and the things he had done. Lincoln, whose parents were illiterate, was a self-taught lawyer, and busy throughout most of his adult life with the rough-and-tumble of politics. He never traveled to Europe, never saw the far West, and never aspired to be a writer in the sense that Jefferson and Theodore Roosevelt did. Language was a tool he learned from a few borrowed books and a lot of practical experience, an instrument of persuasion in courtrooms and a way to make himself trusted and liked in political meetings. He became well known for comical stories in which he was often the object of his humor. He liked to remind audiences of his humble origins. Lincoln was as skillful in his way of portraying himself as were Jefferson, the patrician philosopher, and Teddy Roosevelt, the big-game hunter and gentleman cowboy. Nobody has ever expected me to be president, he wrote. In my poor, lean, lank, face nobody has ever seen that there were any cabbages sprouting out.

But there were two ideas about which he wrote in deadly earnest: the significance of his rise as an example of how any free man in America could improve himself; and the need to protect this freedom against growing threats. These ideas, and the crisis in which they were tested, spurred Lincoln to become not just a wordsmith but a great writer.

The dividing line in Lincolns writing, as in his political career, is May 1854, when Congress passed the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which opened the door to an expansion of slavery beyond the South. Lincoln recognized that this changed the status of slavery from a peculiar local custom to a practice that could be justified anywhere in the United States. In his Fragment on Slavery, written a few months later, Lincoln concluded that if it were possible to justify the enslavement of one person, it would be possible to justify enslaving anyone. There was no logical reason why the institution couldnt envelop people like himself and replace the principle that all men are created equal.

When Lincoln delivered the Cooper Union Address in New York City, he put aside the voice of the self-mocking country lawyer. He declared it was time for opponents of slavery to act upon their moral, social, and political responsibilities. In January 1838, as a twenty-eight-year-old state legislator speaking to the Young Mens Lyceum of Springfield, Illinois, he had prophesied a crisis when the ideals of the founding fathers would be forgotten. When this happened, Reason, cold, calculating, impassioned reason, must furnish all the materials for our future support and defense. That time had come, and Lincoln was prepared to claim the role of spokesman of reason. He didnt need advice from well-meaning New York lawyers about how it should be done.

As incoming president hoping to avoid civil war, Lincoln continued his appeal to reason: My countrymen, one and all, think calmly and well, upon this whole subject, he wrote in the First Inaugural Address. Remonstrating with generals who were unable to perceive their advantages on the battlefield, he cited maxims of war: You seem to act as if this applies against you, he told McClellan, but can not apply in your favor.

But the generals had cause to wonder about the authority of this man who had previously mocked his own military experience, as did his political opponents and even allies, many of whom thought they were better qualified to lead, as well as the public, which had elected him president with 40 percent of the popular vote. Was this not the man who joked, Nobody has ever expected me to be president?

Lincolns response was twofold. He minimized his own significance, but no longer in a humorous way: I claim not to have controlled events, but confess plainly that events have controlled me. This, however, is no excuse for passivity: Fellow citizens,