For Lucie and Katie, my two amazing daughters

First published in Great Britain in 2016 by

PEN AND SWORD HISTORY

an imprint of

Pen and Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire S70 2AS

Copyright John Wade, 2016

ISBN: 978 1 47384 901 3

PDF ISBN: 978 1 47384 904 4

EPUB ISBN: 978 1 47384 902 0

PRC ISBN: 978 1 47384 903 7

The right of John Wade to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Printed and bound in England

by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY

Typeset in Times New Roman by

CHIC GRAPHICS

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of Pen & Sword Archaeology, Atlas, Aviation, Battleground, Discovery, Family History, History, Maritime, Military, Naval, Politics, Railways, Select, Social History, Transport, True Crime, Claymore Press, Frontline Books, Leo Cooper, Praetorian Press, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing and Wharncliffe.

For a complete list of Pen and Sword titles please contact

Pen and Sword Books Limited

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Contents

Introduction to an Era

Queen Victoria acceded to the throne on 20 June 1837, at the age of eighteen, and there she remained for a record-breaking reign that lasted a little under sixty-four years (a record only recently beaten by Queen Elizabeth II). Victoria died on 22 January 1901. The age to which the Queen gave her name was a time when the British Empire was at the height of its powers. She ruled more than 450 million people in lands that stretched across the globe to include Africa, India, Canada, the Caribbean, Australia and New Zealand, covering about one quarter of the worlds land mass.

No wonder the Victorians achieved a level of self-confidence that led them to produce so many successful inventors, designers and radical thinkers and not just in Britain. When discussing the Victorian age, it is often accepted as applying only to Britain or, at least, to the lands over which the Queen reigned. But the era in general was equally a hotbed of invention around the world, especially in America and Europe.

Successful inventions

It was an age of ingenuity, inventiveness and innovation that saw the birth of many of the concepts and inventions that are still with us today. Consider a few of those that began life in the Victorian era.

Telephones: Scottish-born Alexander Graham Bell was a professor at Boston University when he worked in his spare time to find a way to send speech over wires. He filed his patent in 1876, beating rival Elisha Gray to the Patent Office by just a few hours and so winning the right to make telephones for public sale.

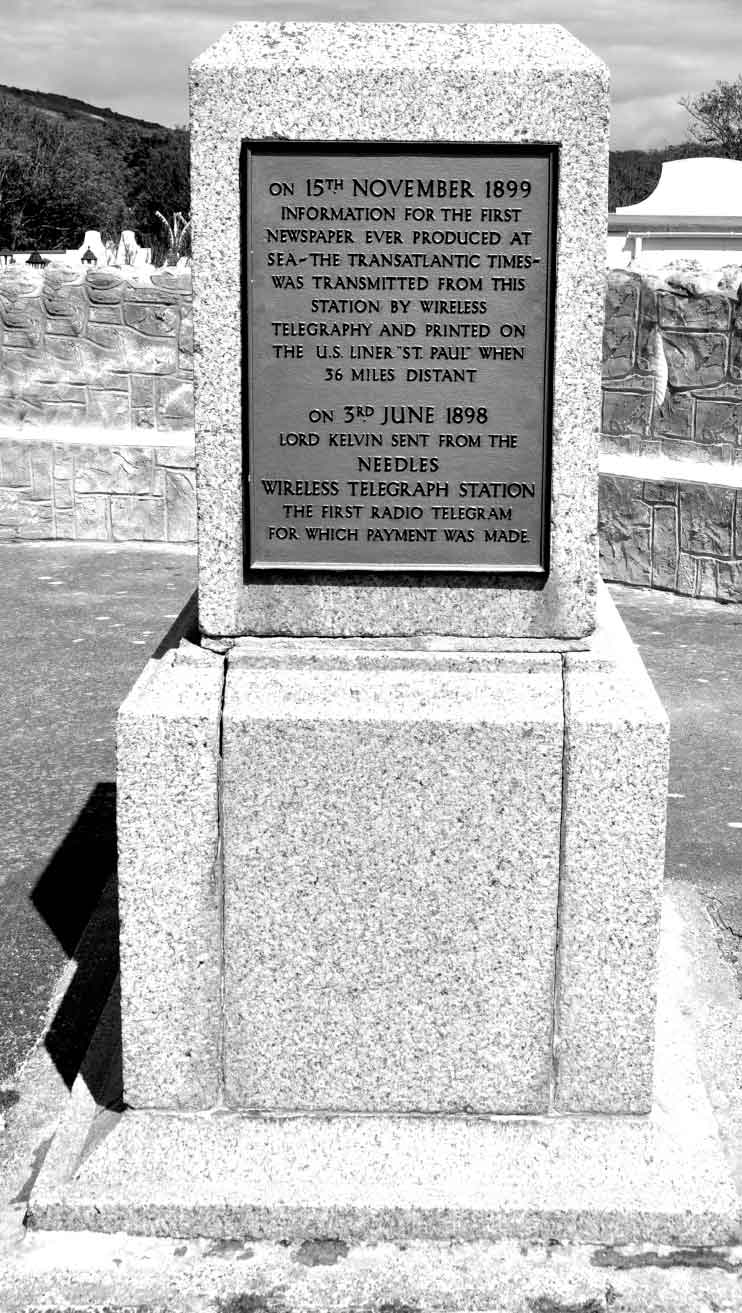

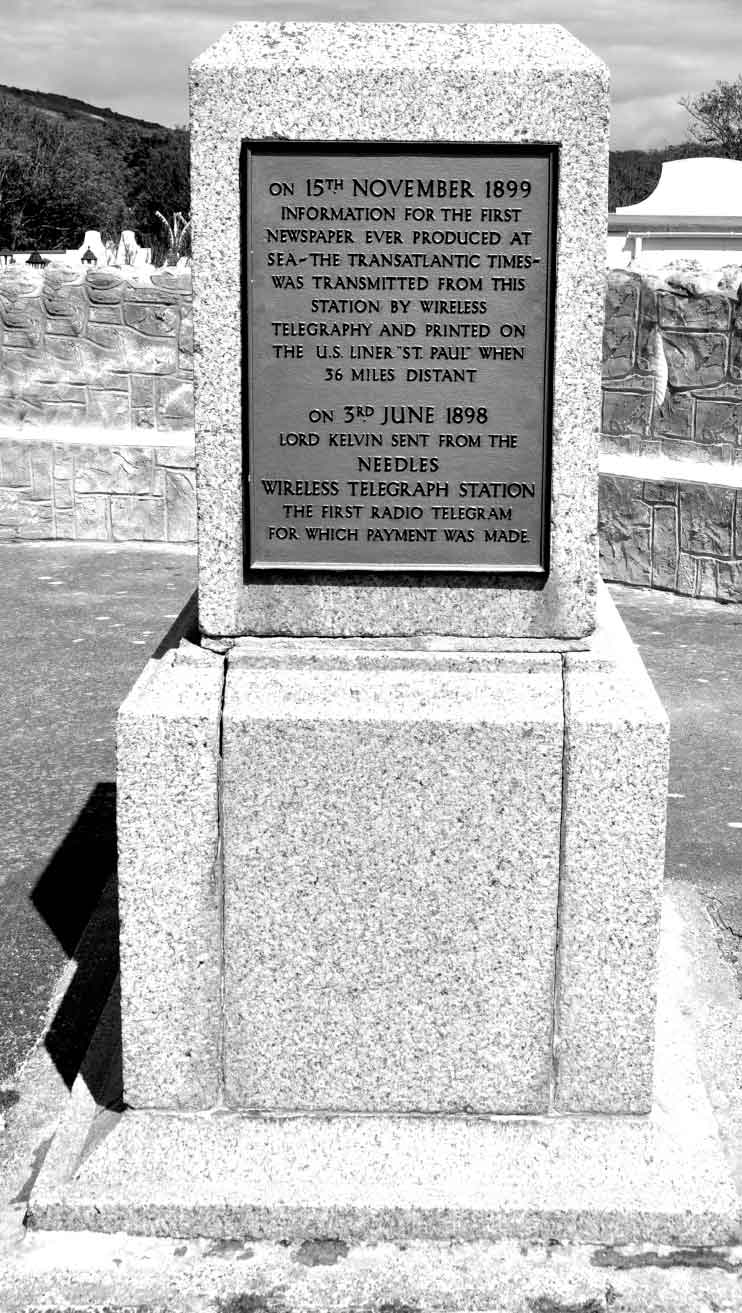

Radio: Guglielmo Marconi, on hearing scientific evidence that invisible waves travelled through the air, set about building a transmitter and a receiver to harness those waves for sending wireless messages. Unable to obtain backing in his native Italy, he travelled to Britain and set up the worlds first permanent wireless station at The Needles, on the Isle of Wight, in 1897. In early experiments, he exchanged wireless messages with a tugboat in nearby Alum Bay, and then with Bournemouth, 14 miles away. In 1898, the worlds first paid for radio telegram was sent from here, and in 1899, information for The Transatlantic Times, the first newspaper produced at sea, was transmitted from this station by wireless telegraphy. Today, a monument to Marconis work stands on the site of the old wireless station.

The monument to Marconis work at The Needles, on the Isle of Wight.

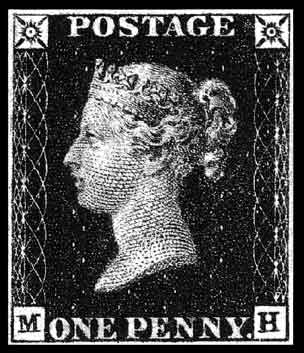

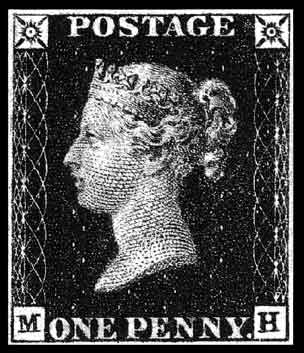

Postage stamps: Until Victorian times, postage on letters was paid by the recipient. English school teacher Rowland Hill saw the inconvenience of this, especially if the recipient couldnt afford, or didnt want, to accept the letter, and so set about producing adhesive stamps, paid for by the sender. The first, launched in 1840, was black, cost one penny to send a letter anywhere in the country and bore an image of Queen Victoria. Pillar boxes erected for the posting of stamped letters were originally green before red, with the monarchs initials on the front, and became the standard in the 1870s.

The Penny Black postage stamp bore Queen Victorias head and enabled letters to be posted anywhere in the country for one penny.

Computers: English mathematician Charles Babbage designed mechanical calculators, the pinnacle of which was his analytical engine, conceived in 1834. It was capable of addition, subtraction, multiplication and division, and could also be programmed using punched cards, inspired by similar devices used in the textile industry for programming looms to weave complex patterns. It could store numbers and separate them from the mathematical processes, and output its results as hard copy, punched cards and graphs. Babbages next innovation, which he called his difference engine, and which he designed between 1847 and 1849, could calculate numbers with up to thirty-one digits. Much of his pioneering work was later reflected in the basic theory behind the workings of todays computers.

Fibre optics: Fibre-optic technology, in which sounds are transmitted by light, became popular in the 1980s. But a century before, in 1880, telephone pioneer Alexander Graham Bell succeeded in transmitting speech from the roof of a nearby school to his laboratory, about 700 feet away, on a modulated beam of light. It worked by directing speech at a flexible mirror, which became convex or concave according to the sound. He called his invention the photophone.

Railways: It was the age of the steam railway, when many already existing small local railways were unified and integrated across the country. As railway fever gripped the nation, a standard gauge (the distance between the rails) was set, magnificent stations were built and amazing feats of engineering resulted in impressive bridges, cavernous tunnels and vertiginous viaducts, a great many of which still survive and are in daily use.

Still in daily use, the brick-built, 100ft high Welwyn Viaduct in Hertfordshire was opened by Queen Victoria in 1850.

Successful concepts

The Victorian age of ingenuity was not confined to inventions. Equally ingenious were the great ideas, plans and concepts that became reality.

Who but the Victorians would have thought of staging an enormous exhibition of world culture and industry, then building the worlds largest glass structure to house it, before tearing the building down, transporting it piece by piece across London and rebuilding it at the centre of probably the worlds first theme park?

Who else would dream of building an electric railway whose lines ran under the sea with the carriage supported on stilts 20 feet above the waves?

What other age could have given us long-lasting electric light bulbs, sound recording, an early attempt at a Channel tunnel, the first flying machines, steam trains under London, life-preserving coffins, four British copies of the French Eiffel Tower and the recipe for Coca-Cola? The Victorians also invented Christmas as we know it today.

Next page