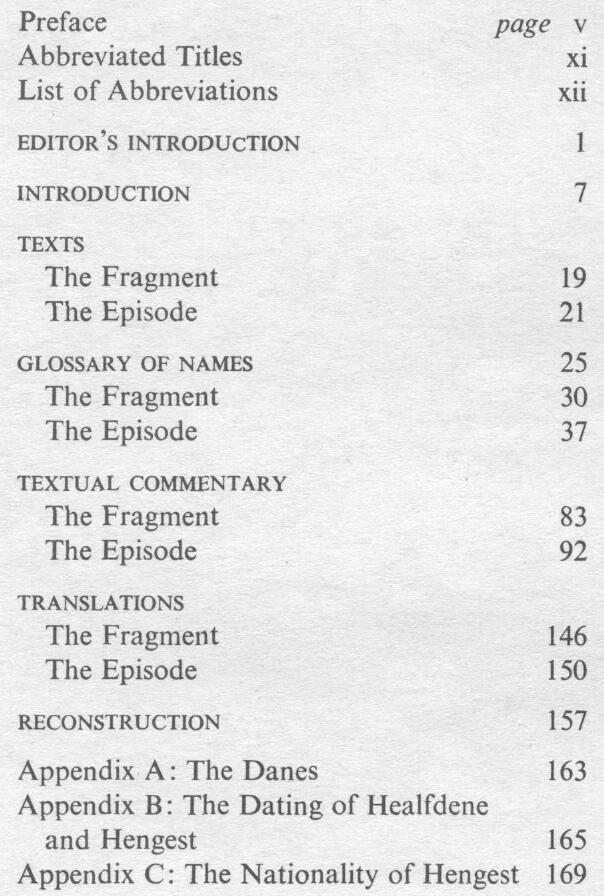

PREFACE

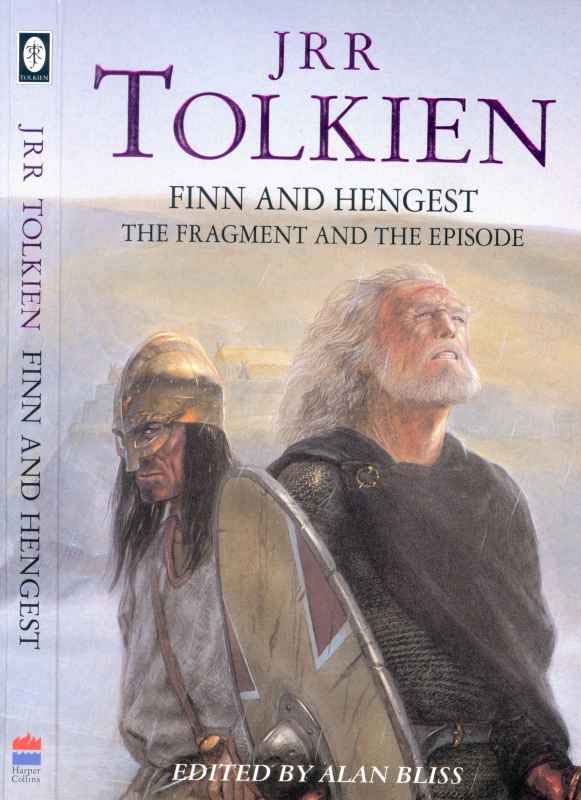

Nearly twenty years ago I read to the Dublin Mediaeval Society a paper entitled Hengest and the Jutes. Later, in conversation with colleagues, I discovered that nearly all my conclusions had been anticipated many years previously in lectures by the late Professor J. R. R. Tolkien, which I had not heard; it was therefore impossible for me to publish my paper. On my next visit to Tolkien, in 1966, I explained the situation to him; a few days later he wrote to me offering, with characteristic generosity, to hand over to me all his material on the story of Finn and Hengest, to make what use of it I wished.

The material was in disorder, and when Tolkien died in 1973 he had still not sorted it out; eventually, through the kindness of Mr Christopher Tolkien, it came into my hands in 1979.

When I read Tolkien's lectures it became obvious to me that I could never make use of his work in any work of my own: not only had he anticipated nearly all my ideas, but he had gone far beyond them in directions which I had never considered. On the other hand it seemed equally obvious that the lectures ought to be published, since they displayed to a high degree the unique blend of philological erudition and poetic imagination which distinguished Tolkien from other scholars. It was suggested to me that I should myself undertake the task of editing Tolkien's lectures for publication.

I did not find it easy to decide whether to accept or decline the invitation: on the one hand I foresaw the great difficulty of the undertaking; on the other hand I remembered that Tolkien himself had wished me to have the handling of his work. Eventually I agreed to undertake the task, and this book is the outcome of my efforts.

It is the custom in Oxford for the Rawlinson and Bosworth Professor of Anglo-Saxon to lecture regularly on Beowulf, and in the twenty years (1925-45) during which Tolkien occupied the Chair few years passed in which he did not deliver the expected lectures. Between 1928 and 1937 he also lectured six times specifically on the story of Finn and Hengest. The title of the lecture-course varied -The Fight at Finnesburg and the Finn Episode (1928),

Finn and Hengest: the problem of the Episode in Beowulf and the Fragment (1930), Finn and Hengest: the Fragment and the

FINN AND HENGEST

Episode (textual study, and reconstruction) (1931), The Fight at Finnesburg (1934), Finn and Hengest (1935, 1937) - but no doubt the material remained essentially the same, even if it was revised in detail from time to time. A seventh course of lectures, under the title The Freswl (Episode and Fragment), was announced for Michaelmas Term 1939, but on the outbreak of war the published lecture-list was cancelled, and these lectures were not delivered. During the war years Tolkien lectured regularly on Beowulf, and it appears that he devoted more attention than previously to the

Finn Episode, to compensate for the lack of a separate lecture-course on Finn and Hengest. In 1962 Tolkien emerged from retirement during the absence in America of Professor C. L. Wrenn, his successor in the Rawlinson and Bosworth Chair, and in Hilary Term 1963 he delivered a course of lectures under the same title as the ill-fated lectures of 1939.

It will be seen, then, that there are three periods in which Tolkien is likely to have worked most intensively on the story of Finn and Hengest, about 1930, about 1940, and about 1960; and these three periods are reflected in the surviving material. The most substantial block of material no doubt formed the basis of the lectures on Finn and Hengest from 1928 onwards. This consists of four main parts: a study of the proper names in the Fragment and the Episode, arranged in the order in which they occur; notes on the text of the Fragment; notes on the text of the Episode; and a reconstruction of the story underlying the remains. The first of these four parts also exists in a much longer and fuller version: this may have been prepared for publication, since it is more carefully penned in a more formal style, and is liberally supplied with footnotes. Another set of lecture-notes on the Episode (as far as line 1143) seems to have been extracted from the lectures on Beowulf delivered during the war-years; some pages are written on the back of duplicated notices dated late in 1939 or early in 1940. The first part of these notes, as far as line 1087, was revised and expanded, so that there is an overlap in the page-numbering; since the revised notes refer to the last time (1941) that the lectures were given, the revision probably belongs to 1942. Finally there is a bundle of Later Material, not all of which is in fact very late: it includes two versions of a translation of the Episode and an additional reconstruction. An important section of this

vi

PREFACE

later material can be definitely identified as belonging to 1962.

The task facing the editor of this material resembles the task facing Tolkien himself when in his last years he envisaged revising The Silmarillion for publication:1 the manuscripts themselves had proliferated, so that he was no longer certain which of them represented his latest thoughts on any particular passage.... He had never decided which was to be the working copy, and often he had amended each of them independently and in contradictory fashion. To produce a consistent and satisfactory text he would have to make a detailed collation of every manuscript. The editor's task is even more intimidating than the author's, since the author stands at least some chance of remembering which was his final view, and he is always free to rewrite; but the editor has neither of these advantages. In many ways the easiest thing to do would have been to write a new book based on Tolkien's ideas: but I have undertaken the more difficult task of producing a consistent and satisfactory text entirely in Tolkien's own words. The only parts of the book which are my own are the Editor's Introduction (pp. 1-6), the translation of the Fragment (pp. 147-9), and Appendix C (pp. 168-80).2

The general plan of this book follows that of Tolkien's early lectures. For the first section, of which the main part is the study of proper names, I have substituted the revised and expanded version which seems to have been prepared for publication. Only one version of the notes on the Fragment is extant, and I have perforce followed that. For the notes on the Episode two or in some cases three versions are available: the early and very full version used in lectures on Finn and Hengest, the later but much briefer version used in the wartime lectures on Beowulf, and in some cases a final version compiled in 1962 or later. The difficulty here is that Tolkien's latest thoughts are often much more briefly expressed than his earlier ideas, so that I have had to choose between lateness and fullness. For this part of the book I have compiled a patchwork of material; wherever Tolkien's ideas seem to have changed little or not at all over the years I have generally preferred the earliest, fullest version; but wherever he rejected his earliest conclusions I have chosen the most lucid

Next page