John Travolta and Samuel L. Jackson in Pulp Fiction, featuring Los Angeles mobsters and a mysterious briefcase.

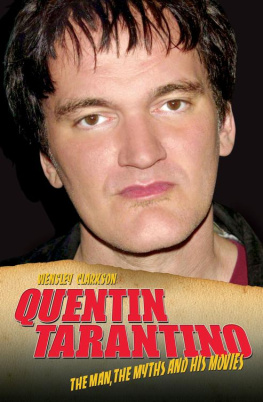

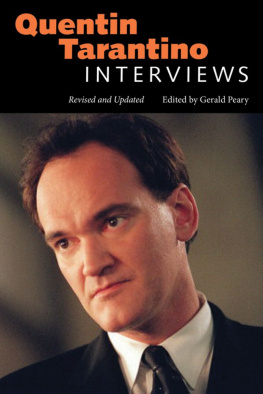

It was towards the end of the summer of 1995 when the British press finally got to see the Second Film by Quentin Tarantino. That was when we finally understood what we were dealing with. We had all heard the rumours, of course; there was no missing the hoopla that had surrounded the former video store clerks triumph at Cannes the previous spring.

H onestly, we were up to speed on the Tarantino phenomenon taking shape on either side of the Atlantic. I had attended the notorious London Film Festival screening of Reservoir Dogs two years earlier, where a noticeable portion of the audience had upped and left, their lips pursed in disgust as Mr. Blonde unsheathed his razor. The rest of us had remained, glued to our seats, horrified and enthralled.

By the time Vincent (in John Travoltas touchingly terrified hands) readied himself to spear Mia Wallace (Uma Thurman, her pale face smeared with blood and heroin snot) with a hypodermic that could have impaled rhino hide, there was genuine screaming: terrified, awed, thrilled not by special effects but by this mix of dread and humour. We were laughing for our lives.

That night, as we left, it felt as if we had woken up.

From the very first, and the very second, and ever since, Tarantino has remained an artist operating entirely on his own terms. He couldnt turn out a routine piece of craftsmanship if he had a gun to his head.

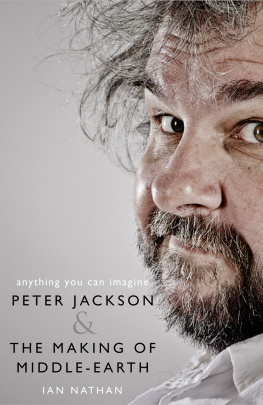

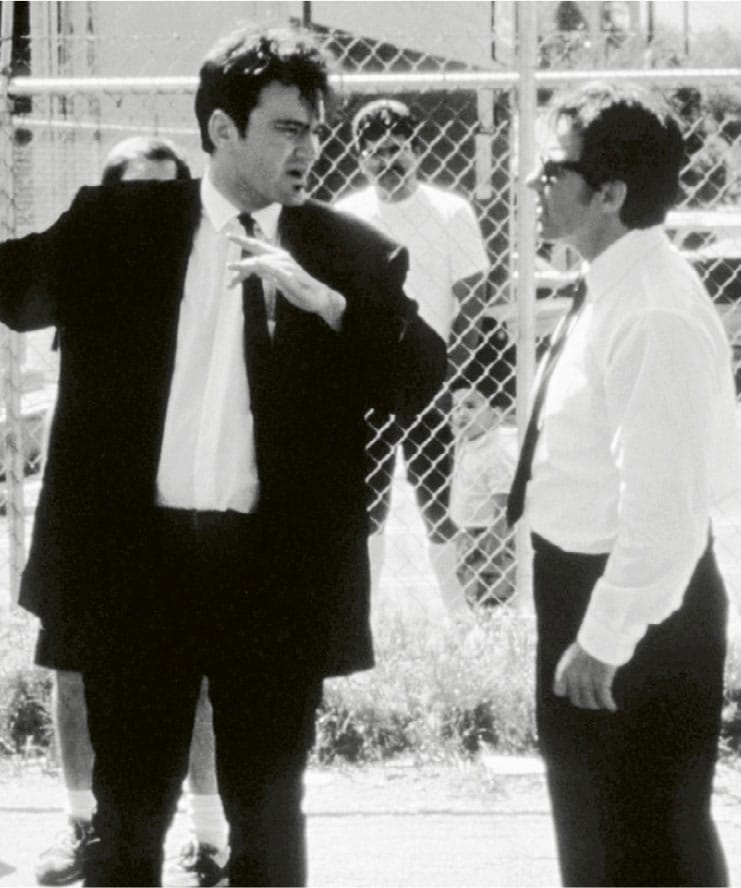

Quentin Tarantino in conversation with Harvey Keitel during the shoot for Reservoir Dogs. While it was his very first film, Tarantino was never intimidated about working with such strong personalities. An ironclad belief in his gifts as filmmaker seemed to be written into his DNA.

He could only ever be Quentin Tarantino, bidden by his talkative characters.

His story became gospel. Overnight from the counter of an outr video store in Manhattan Beach, California where he argued on behalf of cult classics and European auteurs to the most dynamic new voice to hit cinema since Martin Scorsese. Of course, it was a whole lot more complicated and interesting than that, but you get the gist. Here was a glimpse of possibility for every hopeful outsider.

That is key to the Tarantino myth the optimism that accompanied him. He was the messiah of film geeks.

His is a voice made from movies. Has he seen every movie ever made? Maybe not quite, but he must have come close. Celluloid runs through his veins, slice him with a razor blade and he will bleed movies. The Good, The Bad and The Ugly remains his all-time favourite (for now), but he is open to all-comers, able to find as many rewards in the scuzziest drive-in shocker as any arthouse darling.

Thankfully, he has outlasted his own cult, matured, but never compromised. His eighth and latest, The Hateful Eight (2015), stands amongst his best. He is a paradox that Hollywood still cant fathom. A marriage made of art and commerce; trash and humanity; violence and laughter. These are stories that ride high on their own artifice, yet feel real. His gift is to fuse the illusions of cinema with the rhythms of life to see what comes of it.

Warping beloved genres has always been his way into a story, and his canon has covered crime, horror, Western and war movies (and subdivisions thereof). Truly, though, these are films about human folly, and what binds and separates us; about communication, language, violence, race, underworld ethics and righteous fury; about reinventing form and dancing with time; and that singular conundrum known as America.

Unlike so many other filmmakers who struggle to elaborate their creative process, in interview Tarantino is hyper-articulate. With every answer to every question it sounds like he is quoting from a biography already written in his head. There is no one better on Tarantino than Tarantino. Here is an ego like a tumbling waterfall, and with a drive to match.

Beware, though, he is a self-mythologizer too, which is all part of the fun. This book is not only a celebration of his career but an attempt to decipher the fire-hydrant spills of those answers, and all the inspirations and connections that marry and separate his still relatively compact output.

What is incontestable is that he has put his money where his mouth is. Courting controversy with every new addition to the oeuvre (and wearily dismissing the charges of violence, racism and general moral pollution his films are deceptively moral), he has fashioned some of the most significant and unforgettable films of the last twenty-five years.

To quote Pulp Fiction, and Travoltas ever-inquisitive hitman Vincent, Thats a pretty good fucking milkshake.

Time to get into character

Uma Thurman as Mia Wallace, and her five dollar shake. It was the triumph of Pulp Fiction that confirmed Tarantino was no flash in the pan, but a revolutionary who married art and commerce in a way that has remained true for his entire career.

I DIDNT GO TO FILM SCHOOL, I WENT TO FILMS.

Video Archives

Why is Quentin Quentin? The answer is both simple and telling. Late in her pregnancy, Connie Tarantino henceforth the redoubtable Connie became hooked on the Western serial Gunsmoke, featuring a young Burt Reynolds as Quint Asper, the half-Comanche blacksmith who appeared for three seasons. Connie is half Cherokee, a fact which would contribute an aura of mystery to her extraordinary son. Something she dismissed as sensationalism.

Q uint, however, sounded a tad too casual to her ears, and reading William Faulkners The Sound and the Fury led her to the similar but more upstanding Quentin, the name belonging to a smart, introspective and somewhat neurotic son of the pivotal Compson clan. So Quentin became Quentin thanks to a mix of high and low culture: the cheesy TV serial paired with a great American novel with its whirling array of charcters and voices. Connie and many of his early friends would know him better as Q.